Two very different games about politics: Yes, Prime Minister and Floor 13

We're rerunning Richard Cobbett's classic Crapshoot column, in which he rolled the dice and took a chance on obscure games—both good and bad.

From 2010 to 2014 Richard Cobbett wrote Crapshoot, a column about rolling the dice to bring random obscure games back into the light. This week, absolute power corrupts absolutely. What fun would it be otherwise? Of course, it's often not all it's cracked up to be.

It's time to get a little political. Two games offering a chance to wield power, two very different methods, and two chances to find out how the country is really run. The answer, of course, is 'by the whim of the lizard people'. But they'll always need middle-management.

First up, it's the respectable face of British politics. Yes, Prime Minister (originally simply Yes, Minister) ran in the 1980s, and was an institution. People loved The Thick Of It for its sweariness and modern cynicism, but Yes, Minister was so big that actual sitting Prime Minister Maggie "The Iron Lady" Thatcher wrote and performed self-insertion fan-fiction for it. Despite her approval though, it was a wonderful series—a carefully researched and scalpel-sharp show about the power struggles between politicians and administrators to control and manipulate and sometimes even get things done. Sometimes.

Mostly, that fight is between the leads—politician Jim Hacker, whose initial idealism doesn't last long under the constant, co-ordinated assault of his officials, and Sir Humphrey Appleby, his Permanent/Cabinet Secretary, whose intellect and loquaciousness vis-a-vis operating procedures can occasionally manifest, from time to time, in rather artificially extended explanations and advice of a political and advisory nature subject to, but unrestricted to, both necessary and unnecessary confusion of a self-beneficial slant masquerading as impartial thinking of a professionally unbiased nature, in the finest traditions of the Home Civil Service. Or, in the words of Aristotle, words are his bitch.

It's worth checking out the series if you haven't already. The writing and acting are terrific, smart and terrifyingly accurate to the point that it's said to have been used as a training tool for new politicians. The development of the characters over the years is also very satisfying to watch—especially as Hacker starts to become wise to the trickery around him and learns how to fight back. A little. Sadly, the remake misses most of what made it good. Don't judge the whole series on that.

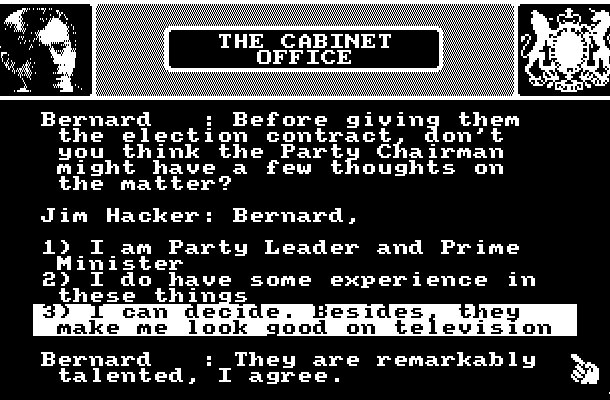

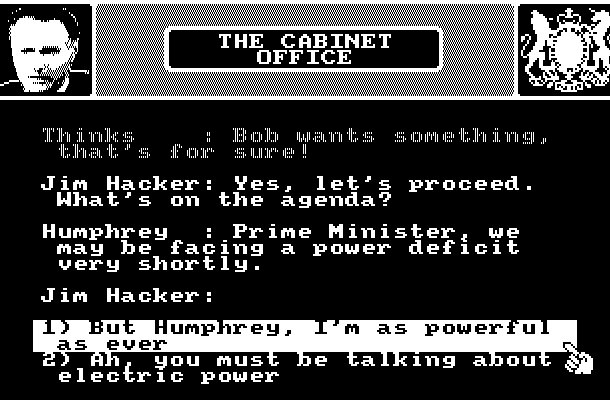

The game version is quite interesting for 1988, at a time when it wouldn't have been too surprising to see someone get hold of the license and quickly knock out a platform game about Hacker jumping over flying red boxes or something. It's a real-time Choose Your Own Adventure type affair that runs in real-time, and gives you a week full of tricky political challenges to navigate. Much like the show, everything is against you and more or less every decision you can make has some hidden trap that the game is only too happy to rub into your face or explain the problem with.

For example:

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

HUMPHREY: Ah, Prime Minister. Do come in. I was just about to phone you about your idea for setting up a Ministry for Women's Affairs.

HACKER: (Blow me, it was my idea, wasn't it?)

HUMPHREY: It will of course...

1) Please radical feminists

2) Annoy your traditional male followers

Not a lot of wiggle-room in those options, are there? If you go with 1, you get:

HUMPHREY: Are they ever pleased, Prime Minister? Depriving them of one of their favourite complaints would probably make them even more annoyed.

The same conversation then goes on to figuring out exactly who you're trying to appeal to. Select "Mothers and housewives" for instance gets Hacker's back up.

HACKER: Humphrey, you can't pigeon-hole women like that! For the sake of convenience let us accept your stereotypes. I suppose we should appeal to

1) Mothers and housewives

2) Career women and professionals

3) Radical feminists

And so on, with political decisions that are often... well, less than politically correct, pushed by Humphrey being more than a little elitist, misogynistic and greedy and Hacker being much shallower and less noble than he likes to think. Here for example, faced with the problem of 'raising gender consciousness', you have to pick which Hacker immediately frets about:

1) Giving them ideas above their station

2) Annoying men

And of course, from there, you get a classic no-win choice—at least politically speaking. Should this new ministry be run by a woman or a man? If you say a woman, Humphrey immediately fires back with:

HUMPHREY: But that's sexist, Prime Minister! Pure anti-male discrimination.

A man then?

HUMPHREY: How very paternalist of you, Prime Minister! It would probably cancel out whatever advantage you might have gained from the whole affair.

And so on, for... well, not long. A week. A long time in politics, of course. Not so much in a game, and especially not one originally written for platforms like the ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64.

Every decision is a tree of bad decisions to make, often impossible choices, and a frustrating lack of moderate options—which actually fits the show pretty well. Hacker spends most of it trying to do the right thing, or at least, thinking he does, despite constantly falling over his own feet and being much less moral and enlightened than he thinks he is. Humphrey spends most of it working by his own internal sense of logic, hammered entirely around Civil Service precedent and its organisational goals superseding everything else—not selfishly, in his eyes, because what's good for the Civil Service is good for the country. If the rest of the country doesn't see that, the fault is theirs.

The result is a surprisingly clever little game. Not a good game, or a complicated game, or a deep one, but one that gets surprisingly close to the show's vibe - warts and all. You're not meant to simply sweep in and make all the right decisions, or even agree with the ones that are deemed 'right' by the game. The system itself is usually against you, everyone has an agenda and information they see absolutely no reason to let you in on, and the only thing you can really do is try to make the right call in the rare moments it's obvious what it is and hope it all works out in the end.

Usually, of course, it doesn't, because as said, the system is against you. Much as Jim Hacker spent most of the series simply trying to stay afloat in a sea of bureaucracy, so do you have to fight the nigh-inevitable failure of having the big chair and very little in the way of clues.

But if it's so hard to get anything done... how do real problems get dealt with?

For that, we need to check in with the hard working spooks of Floor 13.

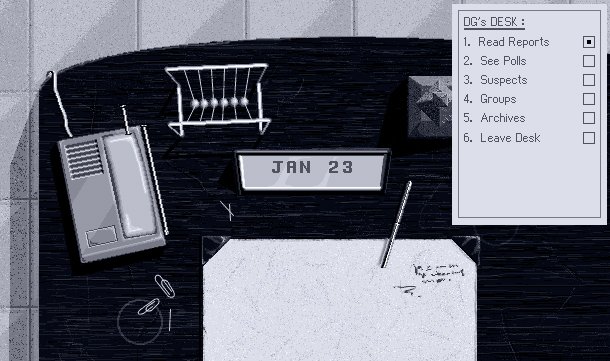

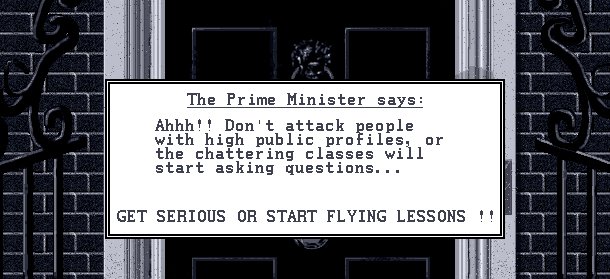

Floor 13 is one of those games with an immediately winning premise—controlling the government's dirty tricks department, and working the job with pretty much complete autonomy as long as you get results. The downside is that if you screw up, you don't get fired. You leave through the nearest window.

While technically under the auspices of the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries—fiction's go-to department for this kind of thing—in reality you work directly for the Prime Minister, and a rather more ruthless one than our friend Jim Hacker. A completely monochrome colour scheme helps build the creepy atmosphere; the ability to casually dispatch hitmen and stick suspects into torture cells does most of the rest. From your desk, you control surveillance, pursuit, 'removal', infiltration and more. Your overall job—to protect the government's poll ratings from falling too much, whatever it takes.

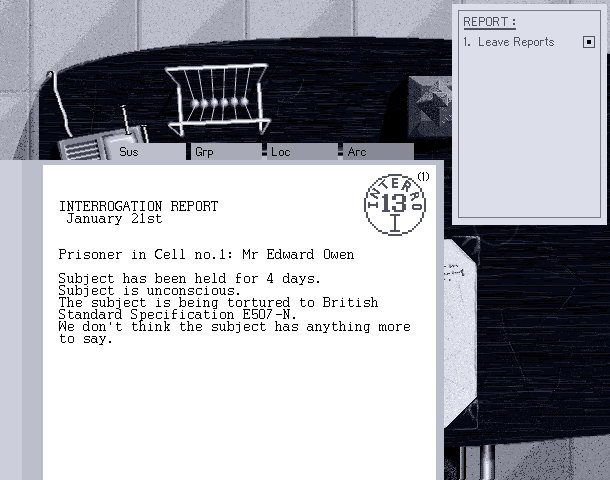

All of Floor 13's challenges are randomly generated every time you play, though you soon get a handle on what sort of procedures it wants you to use. A simple starting assignment for instance might be an Opposition MP trying to sell off national parks—a minor political scandal at most. Unless more information comes in, it's probably something you can deal with behind the scenes. Disinformation maybe, or searching for evidence. If you want to send in a heavy assault squad to cut the problem off at the balls though, or throw the guy in a cell to teach him how to keep quiet, that's your call.

Of course, a politician getting randomly murdered by a hit-squad isn't exactly putting the 'secret' into 'secret police', so that's probably a bad idea that will have the PM invent bollockings the likes of which neither God nor Malcolm Tucker have ever seen before. In short, best leave that for Plan B.

This is one of those games that's primarily played out in your head. Everything is cold, clean and calculated. You don't see strike forces kick down doors. You go into your office, and find a report on your desk informing you that your instructions have been carried out. If an abducted prisoner seems a little comfortable, you don't specify thumbscrews or get involved directly, but simply say "Go to Procedure Two", and go home to whatever awaits there. The only detail you get is "The subject is being tortured to British Standard Specification E507-N", which I believe involves having to watch the same episode of Noel's House Party twice. Not three times though. Christ, no. We have Standards.

The most stylistic flourish is that you're not simply the head of the secret police, but a member of a secret society whose leader is unsurprisingly keen to get a favour or two in exchange for boosting your standing. Getting to that point takes a while though, and more than a few window tumbles.

I always liked this game, though it's a fairly short-lived experience. As with others like it, Sid Meier's Covert Action especially, there's only so long that the randomised challenges can stay interesting, and after a while you start longing for a proper Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy type plot to really sink your teeth into rather than everything lasting a few turns and then being consigned to the shredder.

A modern version though could be really fun, especially tied into Facebook so that another player could be setting up the problems that your department has to deal with. Maybe these two games could even be combined. Over in Yes, Prime Minister 2013, one player accidentally chooses the option that has a prominent foreign politician come over to call the Queen an imperialist whore and also say that Doctor Who is rubbish. Instead of trying to talk their way out of it though, they simply press the "Send To Floor 13" button, where another player is waiting. Waiting, with fingers steepled under chin, and a whole department of assassins and thieves and dirty tricks just waiting for the call.

That could work.

The terrifying thought is that maybe, even probably, it's how it does.