Reappraising Medal of Honor: Allied Assault, one of our highest-scoring shooters ever

War games don't feel like this anymore.

June 6, 1944. Omaha. You’re in a landing craft, waiting. Behind you, a crude representation of a face somehow manages to convey terror. A mortar explodes, hitting the adjacent craft and sending its occupants into the sea. You reach the land. The craft stops and, for a moment, everything is peaceful. Then the whistle blows and the guns start to fire. You run, die and reload, over and over again.

Medal of Honor: Allied Assault is one of the highest-scoring FPSes of PC Gamer’s history. Our reviewer, Steve Brown, praised its confident plot and outstanding level design, calling it “the best FPS we’ve seen since Half-Life”. I, too, have fond memories of the best entry in EA’s Medal of Honor series, and particularly of the atmospheric beach landing sequence. And yet, going back, it’s not quite the standout sequence I remember. It’s not bad, but… well, as painful as it is to say given everything the series has become, Call of Duty did it better.

June 6, 1944. Three miles west of Omaha, and three years after Allied Assault. You’re in a landing craft, waiting. A more realistic-looking soldier empties his stomach over the floor. A mortar explodes. A stray bullet hits one of your squadmates and everybody takes cover. There’s no peace, just escalation. The whistle blows and… you fall. You watch, helpless, as your comrades run and die. Someone is shouting at you, but you can’t hear them over the sound of your beating heart.

Allied Assault feels old fashioned, and not just because it’s 15 years old. The Call of Duty series has changed how war is portrayed in an FPS. The opening of Call of Duty 2’s American campaign, a beach landing on Pointe du Hoc, is directly comparable to Allied Assault’s Omaha mission. Such similarities are unsurprising—Vince Zampella and Jason West were both part of the 2015, Inc. team, and would go on to found Infinity Ward. But what sets Pointe du Hoc apart is Infinity Ward’s talent for set piece design, and an eye for memorable directed experiences that would forever change the genre.

Much of Allied Assault is drawn from Saving Private Ryan, with settings and scenarios recreated from the film. But ironically, despite Spielberg’s involvement with the Medal of Honor series, it’s Call of Duty that feels more cinematic. That moment when you’re lying injured in Pointe du Hoc is drawn directly from the language of film. It’s essentially a Band of Brothers sequence—all excitement and melodrama. It’s also exactly as interactive as a Band of Brothers sequence, by which I mean it isn’t at all. It’s a series of moving images, constructed to not be ruined by a player enacting their agency.

Allied Assault is arguably the better approach, because its design favours playable scenarios over fixed camera placement. Its beach landing is harrowing not because of the scripted deaths of your comrades, but because it’s difficult to play. Making it across the beach requires using the Czech hedgehogs for cover, however they’re an awkward shape—forcing you to jostle squadmates to avoid being pushed out into the gunfire. It’s a loud, tense and disorienting sequence, even though age has stripped away much of its sense of scale. Even playing now, I died a lot.

My many Omaha deaths didn’t make me think about the tragedy of war, so much as the annoyance of quicksaving in a location far away from the one medic hiding across the beach.

Call of Duty 2’s set piece sequence has, alas, aged better, and offers a more consistent and less frustrating experience. Allied Assault’s attempt to craft an atmosphere primarily through interaction is laudable, and feels preferable to CoD’s more directorial approach. But my many Omaha deaths didn’t make me think about the tragedy of war, so much as the annoyance of quicksaving in a location far away from the one medic hiding across the beach. It worked at the time, but I’m looking back through the lens of over a decade of Call of Duty-influenced design. Put simply: CoD won the war, and this is history as written by the victor.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Incidentally, EA’s other war series, Battlefield, produced an affecting sequence about the endless brutality of war that is conveyed through play. Battlefield 1’s prologue switches character on every death, hammering home the relentless churn of lives through the war machine. It’s great, by which I mean it’s very sad.

Across the board, Allied Assault is a product of its time, unaware of the lessons of both Call of Duty and Half-Life 2. But where Omaha is a messy attempt at creating an ambitious, singular experience, elsewhere the lack of heavy direction is a boon. The opening is classic war drama, effectively expressed. You hide in the back of a truck as part of a convoy that’s infiltrating a Nazi camp in North Africa. A guard checks the documentation of the truck behind you, and your squadmates wonder whether he’s buying the ruse. It’s a short introduction that sets the tone, giving the scant justification needed to shoot up a level full of Nazis.

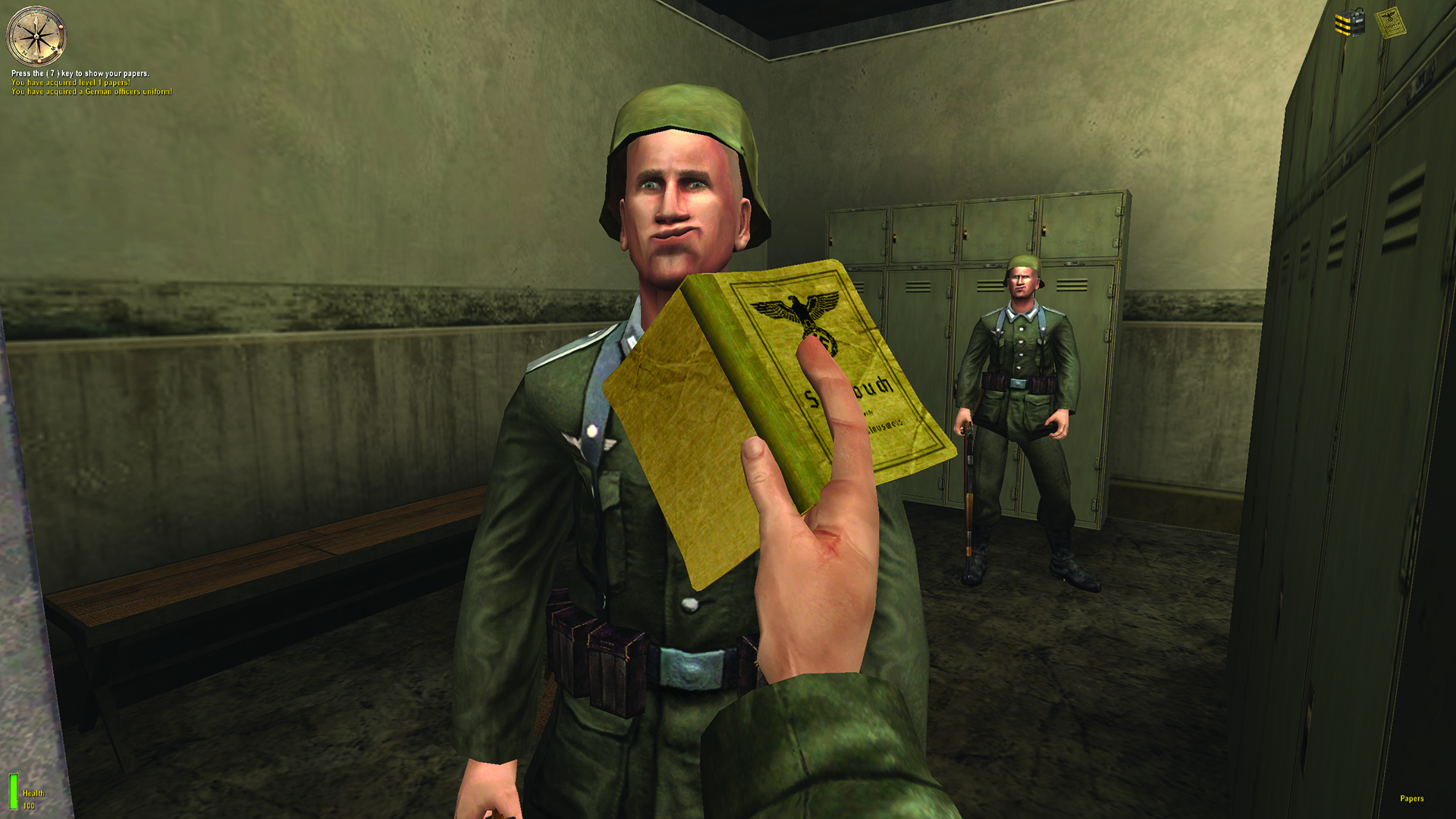

These opening missions feel like a way to bridge the original Medal of Honor games with Allied Assault’s later focus on being the unofficial companion to Saving Private Ryan. Both sections feature excellent mission design and variety. There are stealth sections, sniper sections, solo infiltrations and full-scale invasions. There’s also some turret sections, because, despite everything else, Allied Assault is still a ’00s FPS. There’s a brilliant early mission that involves walking disguised through an enemy base, using a false ID to bypass checkpoints. Still, the lack of a cohesive through line does make the campaign feel scattershot.

The protagonist, Lt Mike Powell—yes, I had to look that up—has no real personality. He’s a cipher for a collection of war experiences, with no story to link them. Neither are his comrades noteworthy. Powell works as part of a squad, but his allies are disposable and quickly killed off. By Omaha, which doesn’t occur until the third chapter, I was desensitised to the plight of the basic AI.

In the years since, FPS campaigns have done more to characterise squadmates, and often use multiple protagonists to justify the whistle stop tour of different war scenarios. It’s easier to connect to characters facing impossible odds than with the vague terror of a terrible war.

Despite time not being kind to its presentation, Allied Assault is still a good shooter. It feels precise, with a focus on longer range combat. If you’re caught by surprise, the enemy can be deadly, and so there’s an emphasis on scouting, particularly in the open areas. Fortunately, Allied Assault features a recreation of the M1 Garand that still holds up. It’s a fantastic gun that’s crisp to fire and has more personality than many of the game’s characters. Allied Assault is no simulation, but a nice quirk is your inability to reload the Garand mid-clip—something considered too awkward to be worth attempting in the middle of a firefight.

Allied Assault is still an entertaining war shooter, and a fascinating step in the journey from Wolfenstein 3D to the upcoming Call of Duty: WW2. That the Medal of Honor series would destroy itself trying to mimic CoD is a shame, because Allied Assault proves that effective systems design can shine outside of Hollywood set pieces. This is, at times, a subtle representation of war, with a lightness of scripting that creates a distinct, now almost unrecognisable tone.

Phil has been writing for PC Gamer for nearly a decade, starting out as a freelance writer covering everything from free games to MMOs. He eventually joined full-time as a news writer, before moving to the magazine to review immersive sims, RPGs and Hitman games. Now he leads PC Gamer's UK team, but still sometimes finds the time to write about his ongoing obsessions with Destiny 2, GTA Online and Apex Legends. When he's not levelling up battle passes, he's checking out the latest tactics game or dipping back into Guild Wars 2. He's largely responsible for the whole Tub Geralt thing, but still isn't sorry.