How the community helped underdog series Fire Pro Wrestling get its second wind

It may have been down, but it never tapped out.

On March 2nd, 2017, Spike Chunsoft made a surprise announcement: Fire Pro Wrestling was coming back, with a new entry on Steam and PlayStation 4. And when I say a surprise announcement, I mean it—it came out of nowhere, preceded by none of the teasing that would typically come with bringing back a series dormant since 2005.

In a normal situation, this would lead to an already niche game quickly forgotten in Steam’s massive library. However, Fire Pro Wrestling has created and fostered a very passionate fanbase over the last 20 years. A fanbase that managed to turn what would otherwise be a blip on the radar into a hit.

A bit of history

Fire Pro Wrestling’s rise in popularity began in the early to mid-90s (the first was released in 1989 for the NEC PC-Engine, produced by the late Masato Masuda and HUMAN Entertainment). This period was the peak of pro wrestling’s popularity in Japan, and the lowest point of its popularity in the West.

It sounded like a wrestling fan's dream come true. Then you played it and found out that it was.

Non-Japanese fans who read wrestling magazines and had the resources for it would take part in tape trading: swapping recordings of various wrestling promotions with other fans via classified ads, making your own copies, and trading them back. Tapes of Japanese wrestling shows were often included. For fans who had grown tired of the bland, sanitized product of the 'Big Leagues' like the WWF and WCW, Japan became something of a Holy Land for exciting wrestling action. And chances are, if you knew how to import Japanese wrestling tapes, you probably also knew how to import Japanese videogames. That’s where Fire Pro comes in.

Like its real-life counterpart, WWF videogames of the time were tedious at best, with characters that were obviously nothing more than mere head-swaps. If you wanted exciting wrestling games, you were not getting them from the US. Thanks mostly to gaming magazines, but also a little bit of word-of-mouth, Fire Pro became known as the game to import.

Having Fire Pro described to me long before I ever actually played it made it sound like the most incredible game in existence. Fire Pro World isn’t (or at least wasn’t) a licensed game, it was less a simulation of one particular promotion, and more a microcosm of Japanese wrestling. It had the athletic, technical style of New Japan Pro Wrestling, in addition to the high-flying action of its Junior Heavyweight division. It had the hard-hitting intensity of All Japan Pro Wrestling. It had the dirty, hardcore brawling of places like Frontier Martial-Arts Wrestling and the International Wrestling Association of Japan. It also had "Shoot Fighting", a no-holds-barred style that would later evolve into what we now call Mixed Martial Arts.

And the roster was loaded with copyright-friendly versions of the wrestlers and fighters you had probably already seen on imported tapes. It sounded like a wrestling fan's dream come true. Then you played it and found out that it was.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

With the dawn of emulation came fan translations, of which Super Fire Pro Wrestling X Premium on the Super Famicom enjoyed several. That was the Fire Pro game that introduced something new, which carried over into every subsequent release and was improved significantly in Fire Pro World: AI Logic. It let you not only edit a wrestler’s appearance and moves, but how and when they do those moves.

For example, if you wanted to make Triple H, you could set various attributes to fit his style of wrestling: lots of grappling, keeping things inside the ring, doing illegal moves when the referee isn’t looking, hitting his finishing move when the opponent has taken a critical amount of damage, then going for the pin.

The introduction of AI Logic, with all its variables and conditions (which are surprisingly easy to understand), ensured no two matches are alike, even with the same competitors. This is a problem that plagues other wrestling games, even ones as recent as WWE 2K18, where the matches can become dull and repetitive pretty quickly, with wrestlers not even remotely acting like they do on TV. It also brought about something of a meta game: rather than picking up a controller and playing as a wrestler you made against another wrestler you made, you could set the match to CPU vs CPU, and see how well you had programmed their AI.

The mod scene

This feature, in addition to a number of improvements the game brought and the accessibility of emulation, made it one of the most popular Fire Pros. It also began the sharing of save files—whether emulator savestates, actual SRAM files, or during the PS2 era, the use of things like Dex Drives and Action Replays to upload wrestlers you made and download and import ones made by other players. Of course, this process has since been completely alleviated by World’s use of the Steam Workshop: what once required third-party peripherals and fan-made programs can now be done with a simple click. The ability to share your creations is a major part of Fire Pro Wrestling’s continued success, despite the series having been dormant for over a decade.

Did you want to see a Barbed Wire Deathmatch between Sailor Moon and Utena Tenjou? That exists!

As I’ve been mentioning, Fire Pro Wrestling revolves entirely around its community. There are YouTube channels and Twitch streams dedicated to fictional promotions showing off CPU-simulated match cards. Fan sites with archives of created wrestlers, ring logos, and modding tools to import those things, in addition to mods made for Fire Pro World have been around for years. Fire Pro Arena is the biggest and most well-known fan site, and is absolutely worth checking out. And with all these years of support, it has absolutely helped Fire Pro Wrestling World become as successful as it is.

There are, as of this writing, 34,616 uploads to the game’s Steam Workshop page. Wrestlers take up an average of 7kb each, meaning that you can have an almost limitless roster, wrestling in an almost limitless amount of rings, in matches officiated by an almost limitless amount of referees.

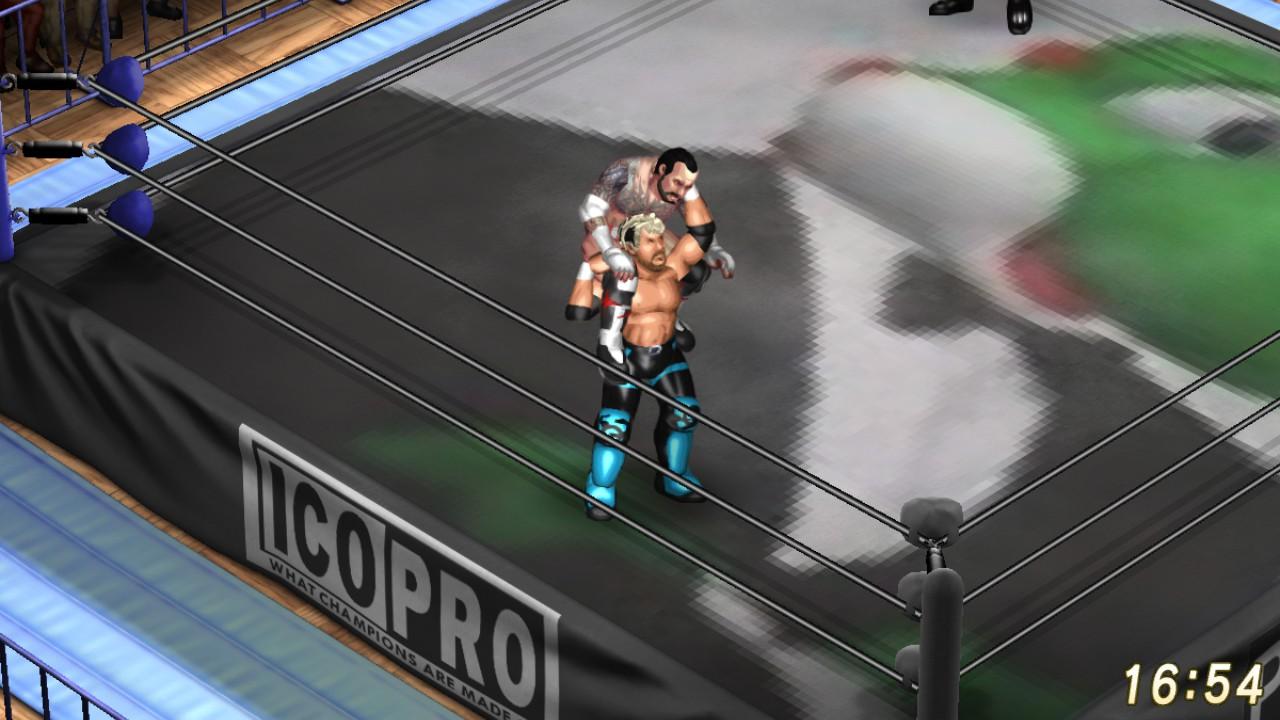

Image via Incredibly Plump Dragon on the Steam Workshop.

And the creations they’ve made are staggering. Very meticulous, near-lifelike recreations of today’s wrestling stars, such as Kenny Omega and John Cena. Just about every era of wrestling has been catered to, from the '90s all the way back to the carnival wrestling days of the early 1900s. Not just wrestlers, but boxers, mixed martial artists, musicians, actors, even anime and videogame characters. Want to see Minoru Suzuki have a match against Night In The Woods’ Mae Borowski? You probably had no idea you wanted to see that, but now you do! Did you want to see a Barbed Wire Deathmatch between Sailor Moon and Utena Tenjou? That exists! A six-man tag team match between the Cheetahmen and Aqua Teen Hunger Force? How about an MMA match between Chelsea Manning and Bonzi Buddy? And I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the literal BEARS as well.

...the community is shockingly nice, given that this is a crossover of videogame and wrestling fans

The game’s tools and the community’s imagination allow for goofy, over-the-top matches you don’t have to be a wrestling fan to be able to appreciate. And as for mods, Carlzilla’s Mod Suite is the go-to. The ability to mix up match stipulations (such as an MMA Battle Royale) is fun, and the FreeCam mod, with its ability to let you show the game off with different camera angles besides the default isometric view, is probably the most used of the bunch.

In addition to being creative and showing a lot of ingenuity, the community is shockingly nice, given that this is a crossover of videogame and wrestling fans, which isn’t exactly a bastion of empathy. Recently the producer of Fire Pro World, Tomoyuki Matsumoto, tearfully announced the introduction of paid DLC for the game during a Spike Chunsoft livestream. And later, an announcement was made that the DLC was going to be delayed. His big fear was that the announcements would drive fans away from the game, a passion project he had spent years trying to get greenlit. And normally, that would be the case: complaints, demands for refunds, maybe even death threats. Instead, there was an almost universal showing of sympathy and support.

It helped that the first piece of DLC was for charity. All the proceeds went to help support Yoshihiro Takayama, a wrestler who was paralyzed from the neck down after a wrestling move went wrong in the middle of a match. But even with the subsequent announcements and delays, there has still been very little in the way of negative reaction. That’s just the kind of community the game has fostered after all this time. Like the tape traders of the '90s, they’re very passionate.

That is Fire Pro Wrestling World. It was born from a series of cult classics kept alive by a determined fanbase, the proliferation of the internet beyond a handful of message boards, and a growing disinterest in the WWE 2K series. And with the current resurgence in popularity of New Japan Pro Wrestling, and a downturn in WWE’s business, it looks like history may very well repeat itself, with wrestling fans tired of a bland product tuning in to Japan’s promotions instead, and telling everyone they know about "this great little videogame you probably haven’t heard of" called Fire Pro Wrestling.