The making of StarCraft

How Blizzard's RTS came to be.

Retro Gamer is an award-winning monthly magazine dedicated to classic games, with in-depth features from across gaming history.

Every couple of weeks, we feature PC-focused articles from across Retro Gamer's long history. This making of StarCraft was originally published in RG170, released in July 2017 (hence the discussion of StarCraft Remastered at the end), and is republished here with the editorial team's permission.

No one could deny the impact that StarCraft had on the games industry. Whether you found yourself Zerg-rushing other players online or playing it years later after the fact, or never even so much as looked at a screenshot, you know this game. StarCraft has become synonymous with RTS games and, at a time when developers were still trying to figure out exactly what could be done with the genre, it was a galvanising title that crystallised much of what we've come to expect from RTS games.

In the mid-'90s, this was an up-and-coming company making a name for itself: Warcraft had been released, its more-important sequel was due to hit the shelves, and even Diablo was on the way. But Blizzard was still a small company then, working on a budget just so it could keep its doors open. It didn't have the resources it has today and it sure as hell wasn't intending for StarCraft to be the game to change all that.

“Well, we had just finished work on Warcraft II,” remembers Patrick Wyatt, one of the key programmers on StarCraft, “it was a product that ran late. And immediately afterwards there was a desire to continue the franchise and to find ways to pay for all of the salaries of the people who were still working.” Patrick alludes to the vast difference between the industry then and the industry now, suggesting that the numbers of sales was often so much smaller than they are today, and it was tougher to get by. “So there was a desire to get back to the next project,” he adds. “And so the idea was that some people were going to go off and start another project and then some of the people who were not the leads on Warcraft II were gonna become leads on StarCraft. StarCraft was envisioned as a sort of an expansion set, and this is how we described it internally… except it was going to be a standalone expansion set. So it wouldn't reinvent everything, and it would be done in 12 months.” This was 1995, with a planned release of 1996; a date the game would not hit.

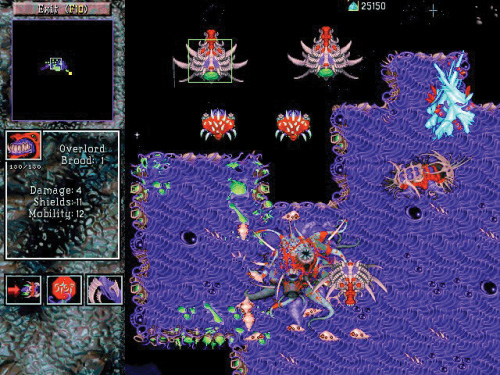

The game's sci-fi theme was intended from the start, says Patrick, explaining that having already covered fantasy with two releases of Warcraft it was now the time for something different. With Command & Conquer having found huge success with its modern military setting, it was clear there was one option for Blizzard from the start—and so initially ‘Orcs in space' was the driving goal for the game. “It was sort of like re-envisioning what would happen if the world of Warcraft just went into space,” Patrick says, “and so the perspective was the same, the art style was a bit different.” Gone was the natural greens and browns of fantasy-fuelled Warcraft, instead here Blizzard opted for something more space-like—a horrific blend of putrid pinks, bright blues and garish greens. It stood out, for sure, but not in a good way. Blizzard found itself the victim of trade show disaster as the team attended E3 1996 to discover that no one was a fan of what would be the company's next game.

It was a defining moment for StarCraft, one that—for as disheartening as it was—bolstered the team. But the real issue was not the negativity that it was met with but, instead, the competition that Blizzard found itself facing. One game in particular, Patrick recalls, was enough to earn the developer some humility: Dominion Storm. “It was just down the hall from us and it had a full isometric perspective, it had a creature that looked like a Star Wars AT-AT walking around, and it just looked impressive in terms of the technology and the artwork, and made us feel embarrassed that we were even on the floor.”

Patrick explains that the team went back to the drawing board after that. Development was reset, and the team had to work hard to make this a title that would stand out in the way that they presumed Dominion Storm would. “It was really that we no longer wanted to do something that was just going to be an expansion,” says Patrick when asked of the sorts of changes they wanted to bring to StarCraft after their E3 showing, “it was to do something that was going to be epic in every sense in the same way that Warcraft was endeavouring to push on every single bound. If we're going to do a space-based RTS, we wanted it to be really credible and something that players would just love and something that we would be proud of. And so there wasn't an official design of what we had to do, it was more like ‘we just need to change everything'.”

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Ironically, Dominion Storm—the game that had been such a decisive reason Blizzard was knocked off its feet and felt pressured into overhauling everything—would go on to release roughly a month after StarCraft. A game so seemingly robust and ready to go at E3 1996 would still take longer to develop and release. The issue, it turns out, was with problems at Ion Storm, but there was a bigger surprise for Patrick and the team at Blizzard. “As Ion Storm started to disintegrate due to financial and political problems,” explains Patrick, “members of its development teams left to pursue other opportunities. From this crew, Blizzard managed to hire Mark Skelton and Patrick Thomas for the company's then-burgeoning cinematics team, where they worked to produce some of Blizzard's epic cutscenes. At some point I talked with Mark and Patrick about how Dominion Storm knocked us on our heels, and they let us in on Ion Storm's secret: the demo was a prerendered movie, and the people who showed the ‘demo' were just pretending to play! It would be an understatement to say that we were gobsmacked; we had been duped into rebooting StarCraft.”

Yet while this faked E3 presence from Dominion Storm may have fooled even reputable game developers, it was a catalyst that ultimately led to a renewed vigour for the StarCraft project. What was once intended as a quick title intended to fill a gap in Blizzard's release schedule turned into a much bigger deal.

“What actually happened was that we were then buried in building Diablo at the time,” says Patrick. Blizzard North was nearing completion of its genre-making action RPG, and it needed a strike team to help things along so that it would reach its targeted release date. “A large percentage of Blizzard staff actually started helping out on that, until finally around December of 1996 basically everybody at Blizzard was not working on StarCraft anymore and, in fact, I had moved up to Blizzard North temporarily and I was working on a bunch of stuff and had written the core of the game installer. But I had so much to do that I was like, ‘I need some help on this,' and so Bob Fitch [technical director on the game], the last person to be working on StarCraft ended up finishing the installer for me. We had zero people on StarCraft, so after Diablo shipped we were like ‘Oh, yeah, this StarCraft game, we should get back to that.'”

It was during this time that Bob Fitch had in fact rewritten the entire game engine. Utilising the time where so few developers were working on StarCraft meant that he was afforded the opportunity to recreate everything, to create a engine that could introduce all the features that they couldn't with the old, 2D Warcraft engine.

“January of 1997 was the reset,” says Patrick, “and it was, ‘Okay, let's rebuild everything. We need to recontrol our design decisions'. Although tragically because it was like, ‘Well, now the project's late so we need to move fast,' and so there were things that we didn't do that we probably should have done at that point. More specifically, one of the biggest pain points that we had from the entire duration of the development was that we had a top-down 2D tile-map game with isometric tiles on top of it, instead of making an isometric tile engine game which made everything else much harder.”

“It made creating the artwork harder, it made pathfinding and AI, in particular, much harder because when you have a diagonal line that's decomposed to these squares, everything becomes kind of jaggy. The pathfinding, as evidenced by the way the Dragoons work, was just a big problem.” Despite the workaround, it was enough to give the StarCraft team the opportunity to turn the game around, to make something special. The “Orcs in space” concept was ditched and Chris Metzen—one of the most important figures for all of Blizzard's fictional universes—came in to create something that was compelling. This meant three different factions to play as, each playing very distinctly from one another.

“Suddenly, when we looked back at Warcraft II, one of the things that was clear after the fact was that the sides were very much a chess piece-like balance, where they're very much interlocking with each other. And it's well balanced but primarily because the units are very similar to one another across both sides,” Patrick says. And that was true of most RTS games at the time.

While the precursor to the RTS genre was Dune II, it was only Westwood's follow up—the much more renowned Command & Conquer—that offered a glimpse at differences between two playable factions. And even then the differences were minimal. “So we wanted to do something where we could do more of a rock-paper-scissors for races and for units,” explains Patrick, “and just be creative and breakout of the chessboard mentally. So three races appealed to us, and then we didn't see the necessity of going with four. We only had so many people and so much time that if you try and spread your ideas over more races then your ideas are going to be thinned out too much.”

With the core elements of the game set, development would roll on for almost a year more, releasing in March of 1998 after much of the team had worked extremely long crunch hours throughout its duration; it was, after all, intended to have been released by 1996. Blizzard—staying true to the developer's approach as much then as it does now—knew it was better to delay a great game than release an unfinished one. This meant there was always room for improvements and innovation, and with the rise of CGI it was clear that Blizzard wanted to be at the forefront of this new approach to storytelling if it was to truly present something that felt believable.

“We were certainly looking a lot at what other game companies were doing and being inspired by what they did,” admits Patrick, “and so it was always a question of how can we take this stuff and go to the next level. I mean we had started with Warcraft doing cinematics with just two people, and it was amazing for its time and the limited resources. It was all put together in 8-12 weeks by two people for Warcraft, and we started having more and more cinematic artists join and create things that were really impressive in a way that they extended the game. They told a story and they created a reward for people who played to the game to really get into the world, and not just the gameplay: there was this believable world behind it and so it just seemed really natural to continue that.”

Limitations still applied, of course. “I will say that we did only have a really small cinematics team that did all that stuff,” Patrick says, “learning the tools—inadequate tools—and discovering how, on a budget, to render these scenes. We didn't even have render farms, we sort of built it out of desktops when people weren't using them sometimes. So it was just a huge challenge being so resource constrained in that era.”

That devotion ultimately paid off. StarCraft was released to immediate success, selling a huge 1.5 million in its first year before going on to achieve 9.5 million copies sold worldwide. Critics praised the title, suggesting it was the standard by which all RTS games will be measured. Today, the concept of a ‘Zerg-rush' is still well known and referenced, while design elements of the game are still prevalent through practically every RTS game since.

But more than anything, StarCraft is a game that even now has an active player base, a facet helped along by its multiplayer mode that had helped to boost the game's popularity as much in the US and Europe as it did, unexpectedly, in South Korea—where, as a result, the home of competitive gaming was born. Now, Blizzard is remastering StarCraft, bringing in up-to-date visuals and HD audio. If nothing else, Blizzard is now offering up the unpolished original for free—a chance to relive the classic, regardless of whether you've played it before or not.