The Japanese PC that ran the original Metal Gear is coming back after 30 years of extinction

The MSX's co-creator is back with a new model, the MSX3, and it's coming this year.

The MSX PC is barely known in the West, but it was Microsoft Japan's big 1980s play for parts of the Asian computer market. A joint project with the ASCII Corporation, the MSX was an attempt to create a 'standard' PC architecture in the same way that VHS had become the de facto videotape format.

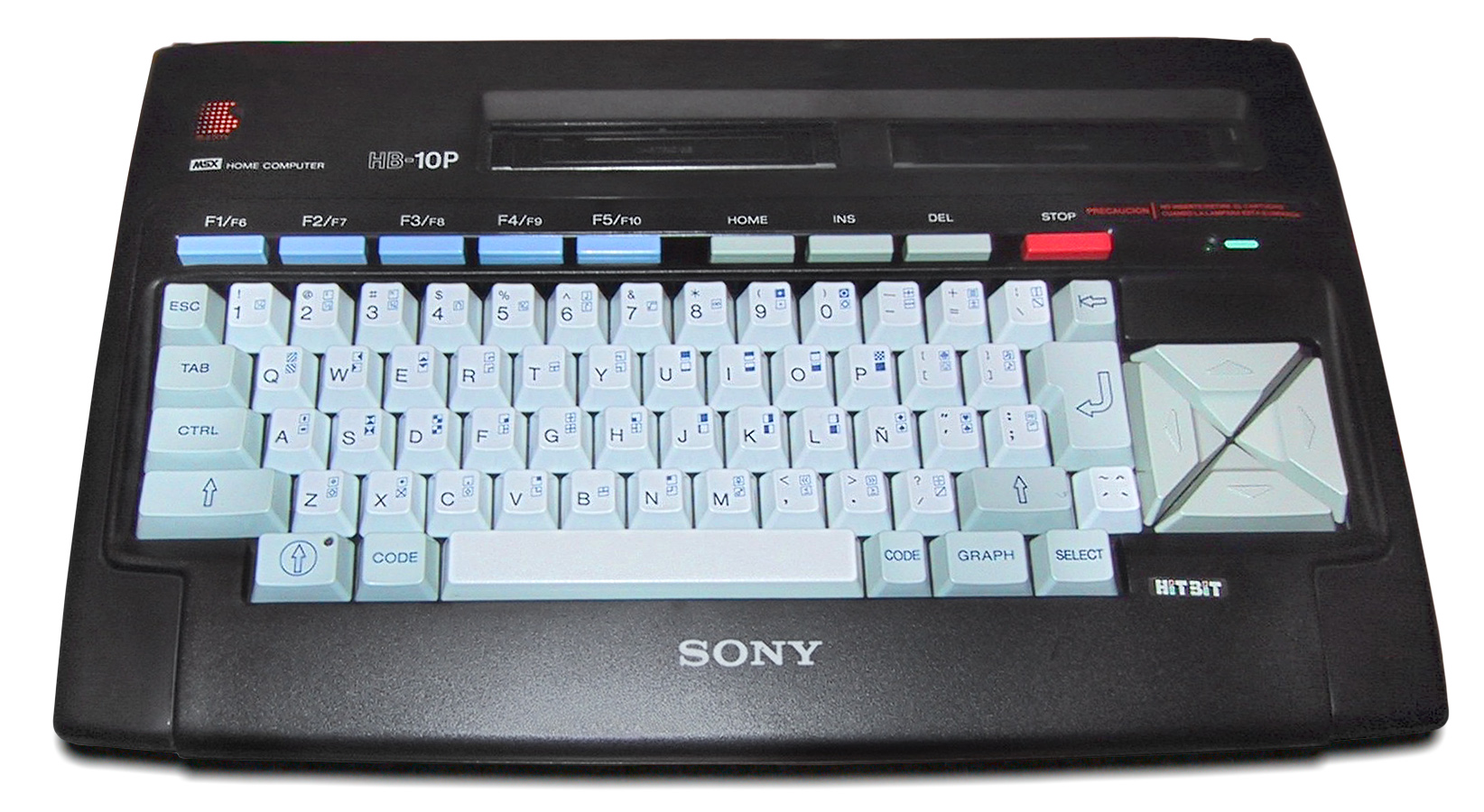

The first MSX systems were manufactured by Mitsubishi and launched in October 1983 in Japan (though the whole point was that any company could manufacture them, which many including Sony did). Seven million MSX machines would be sold in Japan over the next years, making it both a viable games platform (the Metal Gear series began on MSX2) and a part of the cultural fabric. It was always an underdog, but beloved in its day.

The co-founder of ASCII corporation is the extraordinarily accomplished engineer Kazuhiko Nishi, who as well as co-designing the MSX is a creator, a businessman, and a professor. The other co-creator is Kazuyasu Maeda, who was from Matsushita R&D. There were four generations of MSX hardware, with the last being 1990's MSXTurboR (discontinued in 1993). The anticipated MSX3 never materialised.

ASCII became defunct following a 2008 merger, but Nishi has now designed something remarkable in partnership with D4 Enterprise: the standalone MSX3, to be launched later this year.

Dear Friends,D4E president Mr. Suzuki agreed today they will launch 1 chip MSX 3 as their primary console for the EGG. As a option, will have a bay slot for DVDR or BDXLR and will support for CD, DVD, BD, BDUHD. Announcement for 1 chip MSX 3 by the end of summer.best regards, pic.twitter.com/oDUFIFT2waJune 23, 2022

D4 Enterprise is a Japanese video game publisher that specialises in game preservation, and operates Project EGG. Its aim is to get MSX games on modern platforms, essentially, and keep the rich history of the hardware alive.

The "next-generation MSX" is somewhat in keeping with that, but the intention also seems to be a machine that is more than just a hobbyist nostalgia piece. It has an Arm-based CPU and supports the C, Python, and LISP languages. The project began as an expansion board which could be installed in the slot of an MSX or MSX2, but is now going to be released as a standalone device with an optional bay slot for DVDs / Blu-Ray disks.

Nishi writes that he had considered making "1-chip" MSX hardware in the old days, but decided that at the time the potential solutions didn't offer enough power. He confirms that the new machine will be backwards-compatible. "Of course old MSX logoed software will run for future MSX," writes Nishi. He also thinks that folk programming should begin using more modern tools: "I will perhaps be asking all potential users stop writing z80 and r800 code anymore and write only on high level tools for 64 bit VM code for long term binary compatibility. VM64 will run on X86, ARM32, ARM64, RISC V."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

More details on the MSX3 will follow this summer, and Nishi says there will be three products available by the end of the year: The MSX Engine 3 "for OEM and hobby system builders", a 'Pro' and a 'Light' MSX3 keyboard, and MSX 3 IOT cartridge to be used standalone or in concert with MSX or MSX2 hardware.

Don't call it a comeback: Though it is incredible to think about a hardware line that's been essentially dead for three decades making its return. And the core idea of MSX, a standardised and powerful PC platform for the masses, is something many companies in many contexts have tried to create over the years (the most recent example, if a bit specialised, is Steam Deck).

Nishi once said that the machine's name came from the design team's guiding phrase: "Machines with Software eXchangeability", although he also at one point said it was named after the MX missile, then in a 2020 book said he went for a three-letter name to align with the VHS standard. Finally, he's said it can also be taken as meaning "the next of Microsoft." So that's crystal clear!

The MSX3 will release later this year.

Rich is a games journalist with 15 years' experience, beginning his career on Edge magazine before working for a wide range of outlets, including Ars Technica, Eurogamer, GamesRadar+, Gamespot, the Guardian, IGN, the New Statesman, Polygon, and Vice. He was the editor of Kotaku UK, the UK arm of Kotaku, for three years before joining PC Gamer. He is the author of a Brief History of Video Games, a full history of the medium, which the Midwest Book Review described as "[a] must-read for serious minded game historians and curious video game connoisseurs alike."