The dark art of Noctropolis, the most gorgeous FMV game you've never played

How an aborted Twin Peaks game, a bizarre trip to Hollywood, and '90s comic art coalesced into an unforgettable adventure.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

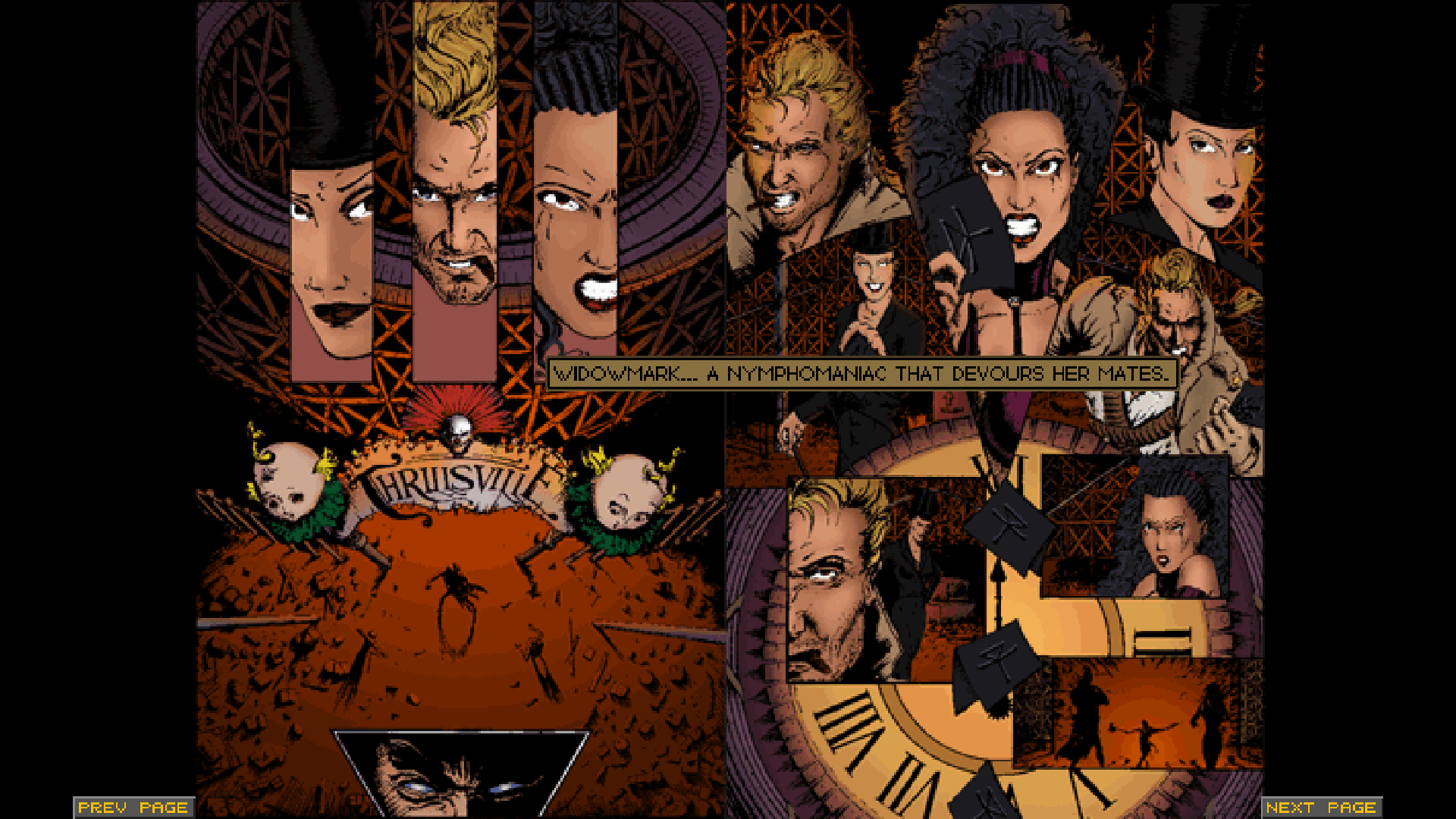

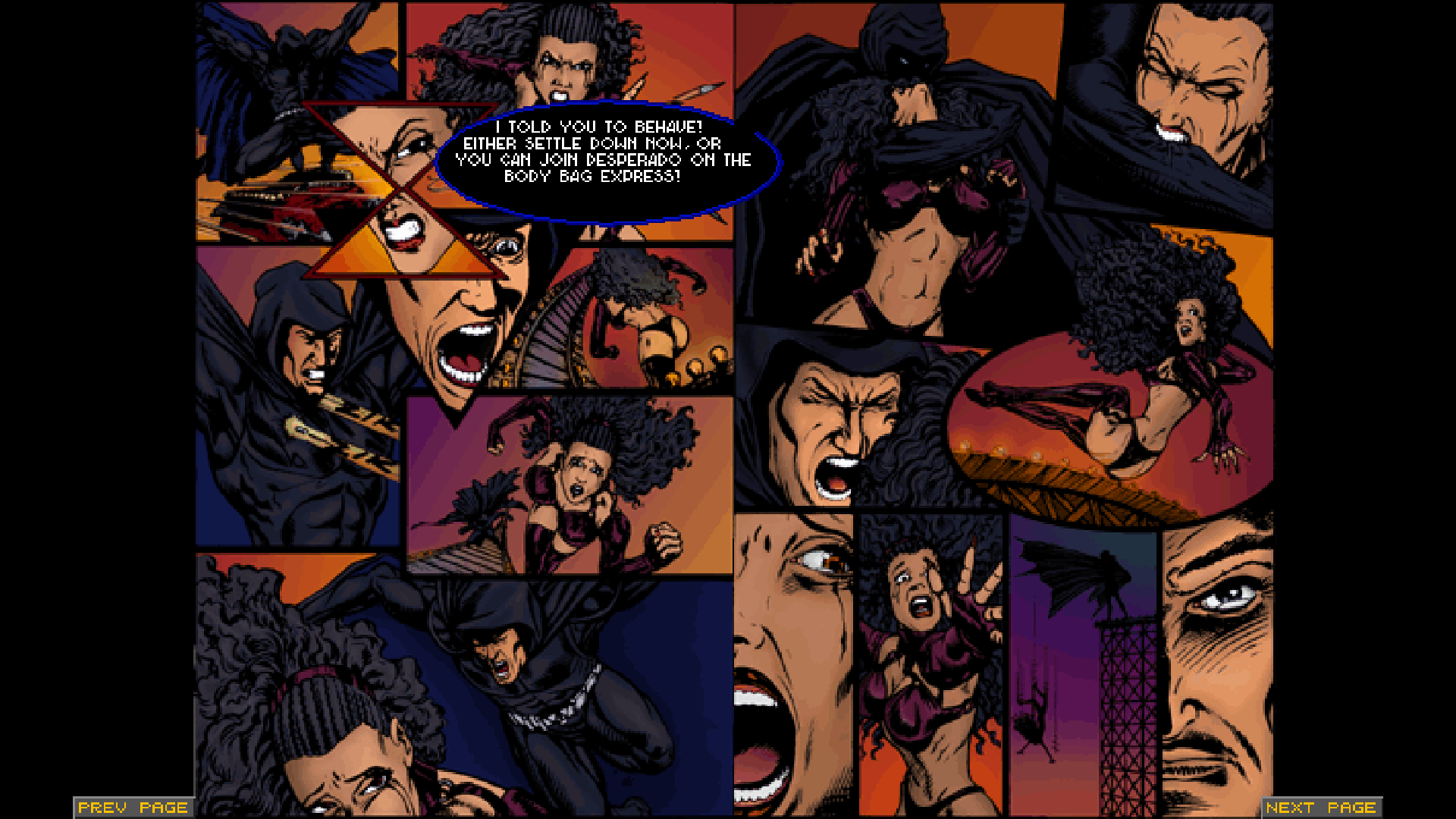

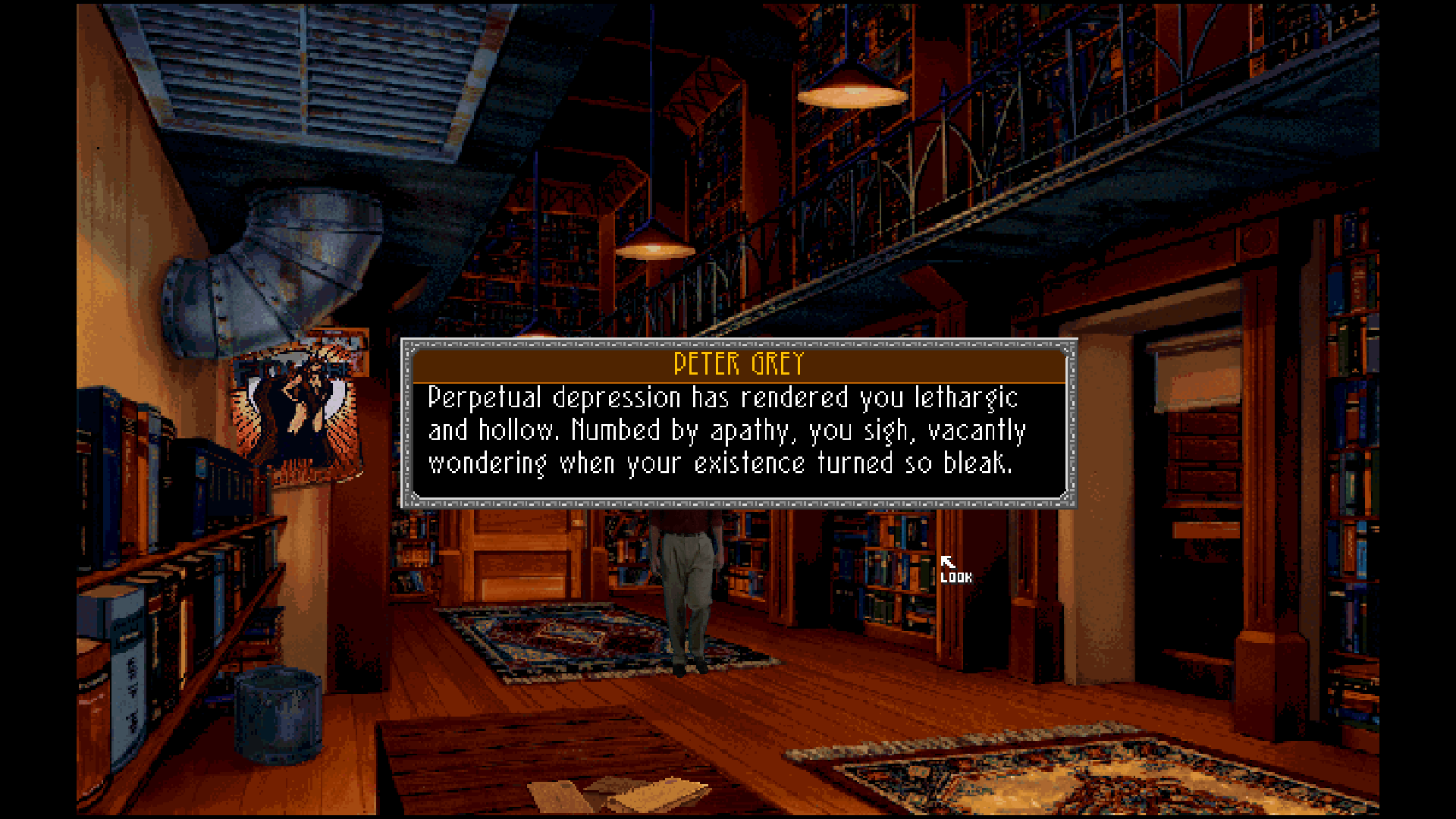

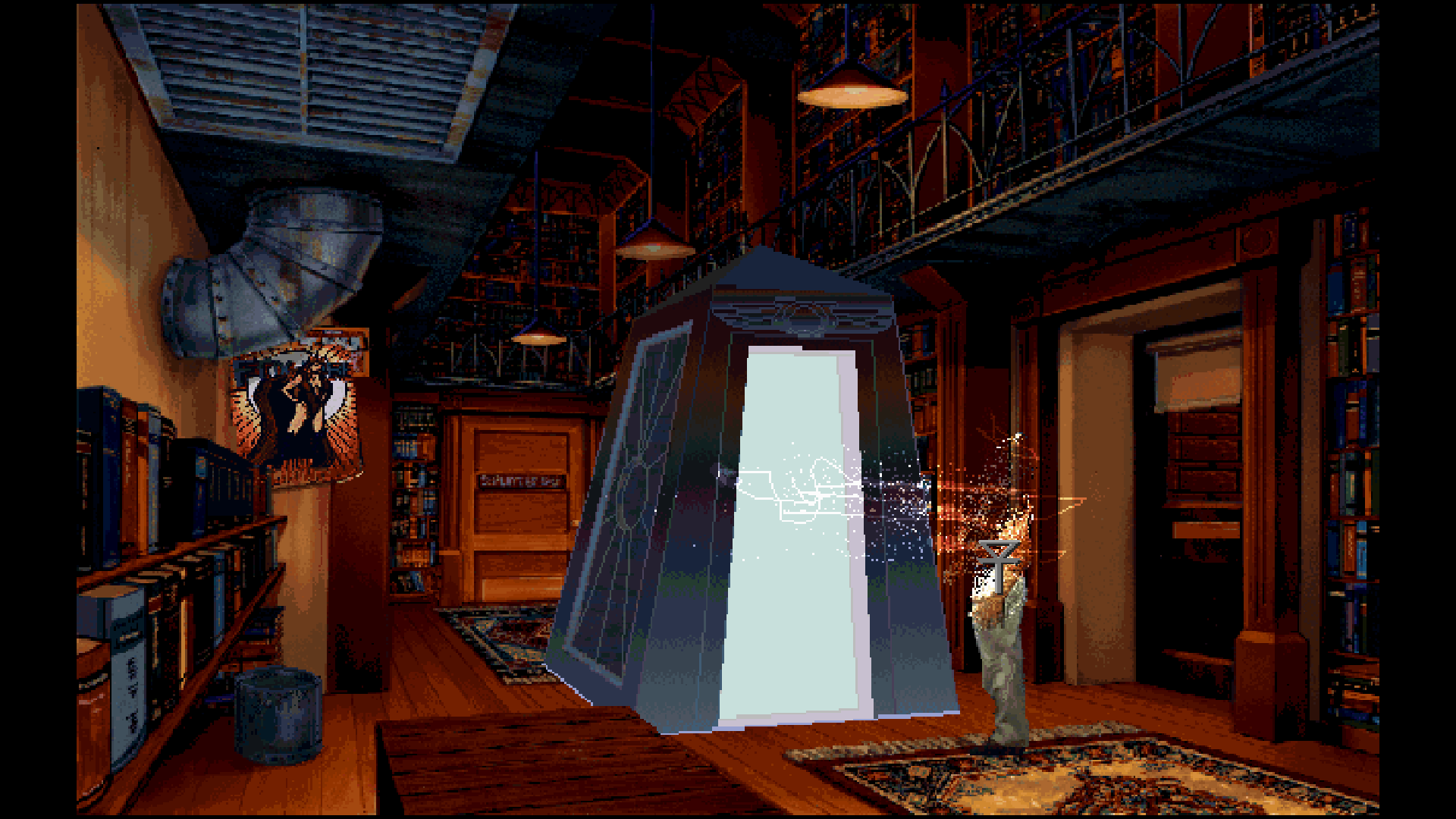

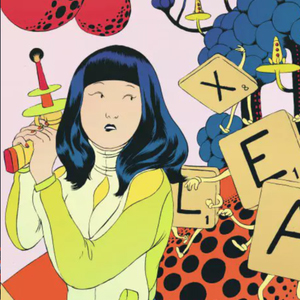

Straight off the bat, Noctropolis unfurls as a midlife crisis in motion. You play a depressed man bogged down by a bitter divorce, unpaid bills, and piles of comic books. Pin-up characters Lady Foxfire and Elastia aren’t your only companions: There’s also the incessant drip of the leaky pipes in your painfully empty bookstore. When a creepy little girl shows up at your door with a mysterious package, it seems you’ve won a sweepstakes contest that’s about to turn things around. And just like that, you’re inexplicably hurled into another world—a byzantine cityscape where it’s always night, caped villains roam the streets, and you have to figure out how to get rid of a sentient gargoyle terrorizing a church.

Perhaps Noctropolis' unorthodox production history is the very reason it became such a beautiful little weirdo in the first place

This light thread of bizarro surrealism is probably the only hint of Noctropolis’ origin as a solution for a Twin Peaks-shaped hole that EA needed to fill.

For about a month in the early '90s, it looked like Shaun Mitchell and Brent Erickson were going to get to make a Twin Peaks game. Imagine an FMV adventure based on David Lynch's TV show, with run-ins with locals like the Log Lady (she'd offer you cryptic hints, of course). EA had the license, and Mitchell and Erickson's independent studio Flashpoint got to work on that fever dream of a game idea for just a few weeks. Then the project fell through. They needed to come up with something new, and quickly.

"Our producer at Electronic Arts said, 'hey, what other original properties do you have?'" recalls Mitchell. "Oh, we've got tons of them," he told the producer. "And then we hung up the phone and we were like 'okay, we better come up with something really fast.'" And that's how Noctropolis was born.

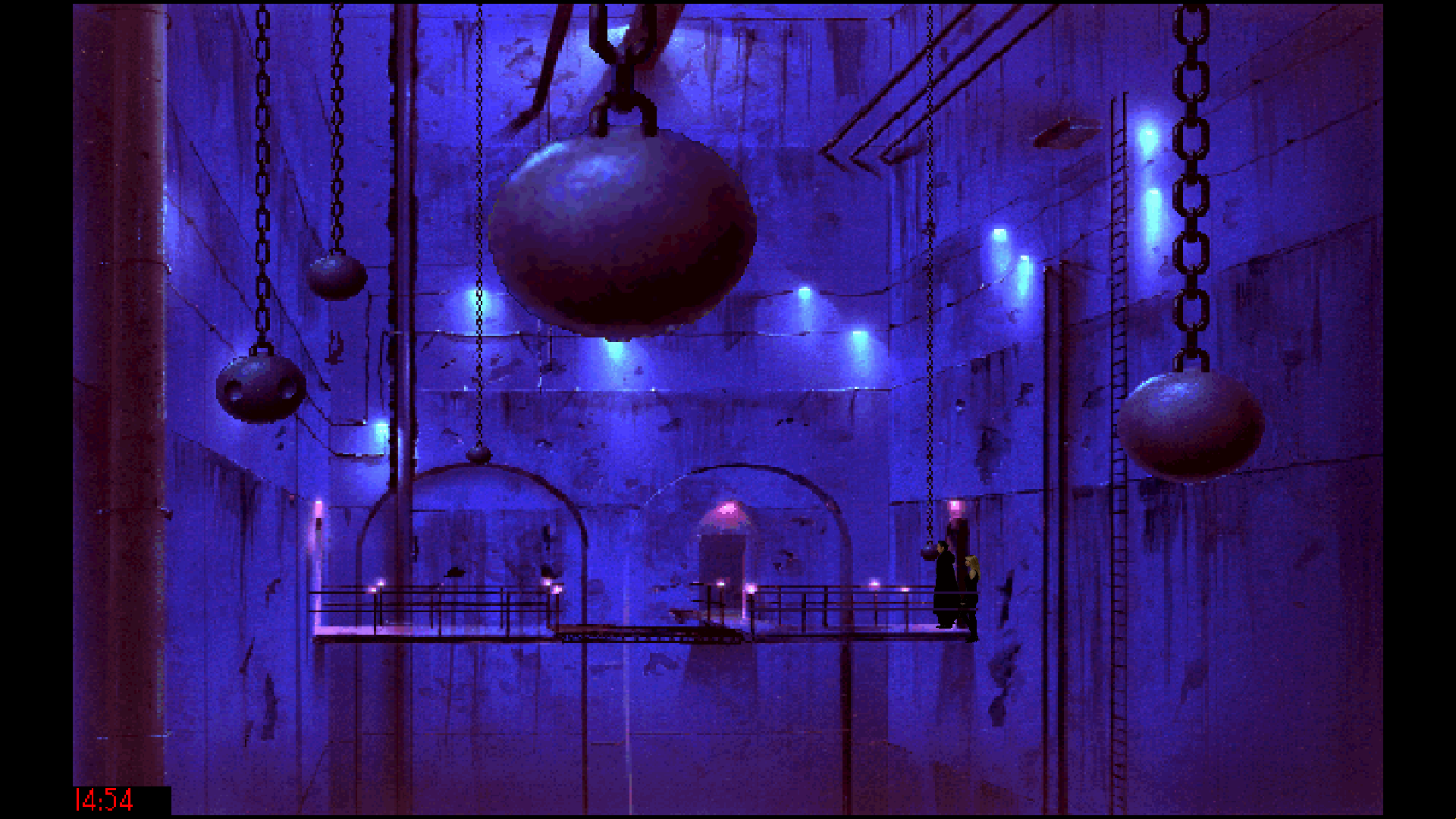

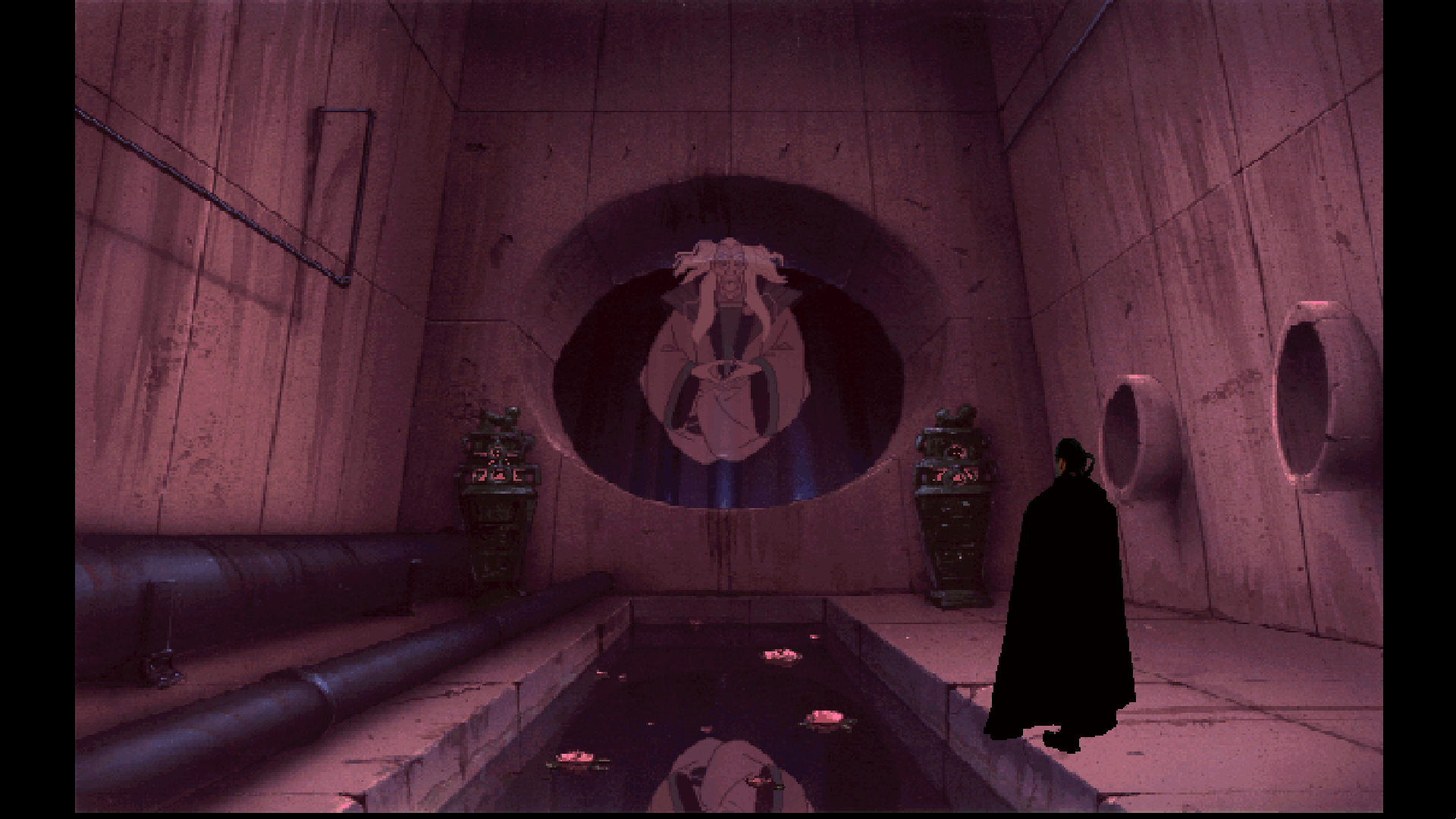

It wasn't an ordinary game by any stretch, though its premise is a familiar trope in the realm of male escapist narratives: protagonist Peter Grey gets sucked into the world of his favorite comic and becomes the superhero Darksheer. Released in 1994, it's very much a product of full-motion video's golden age, a sort of historical cool zone where big game studios didn't really know what they were doing yet. The writing is self-referential, goofy, but endearingly earnest. Its villains are delightfully sardonic send-ups of Batman-style antagonists that range from CGI mutants to prosthetic-clad monstrosities. The UI is, at first sight, fantastically arcane to our 21st-century eyes trained for easy usability—the menu and inventory system force you to engage with the game’s aesthetics on its terms, not yours.

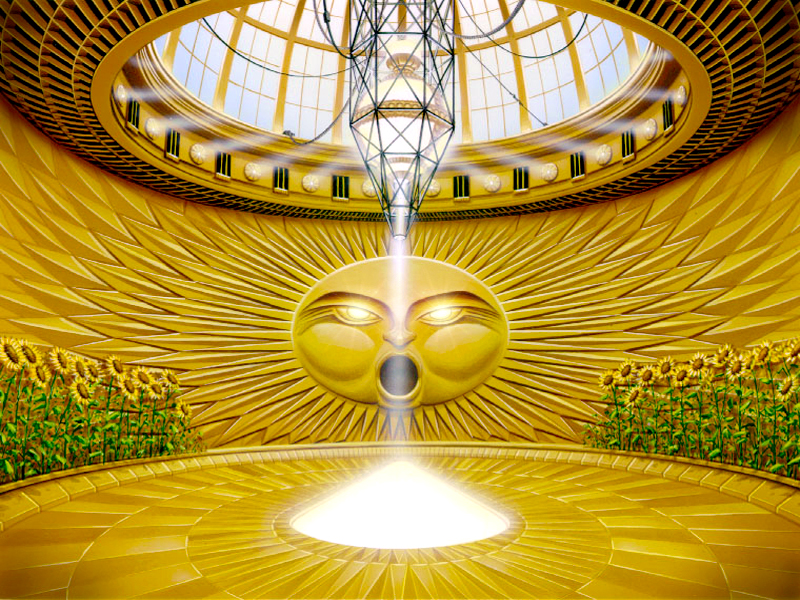

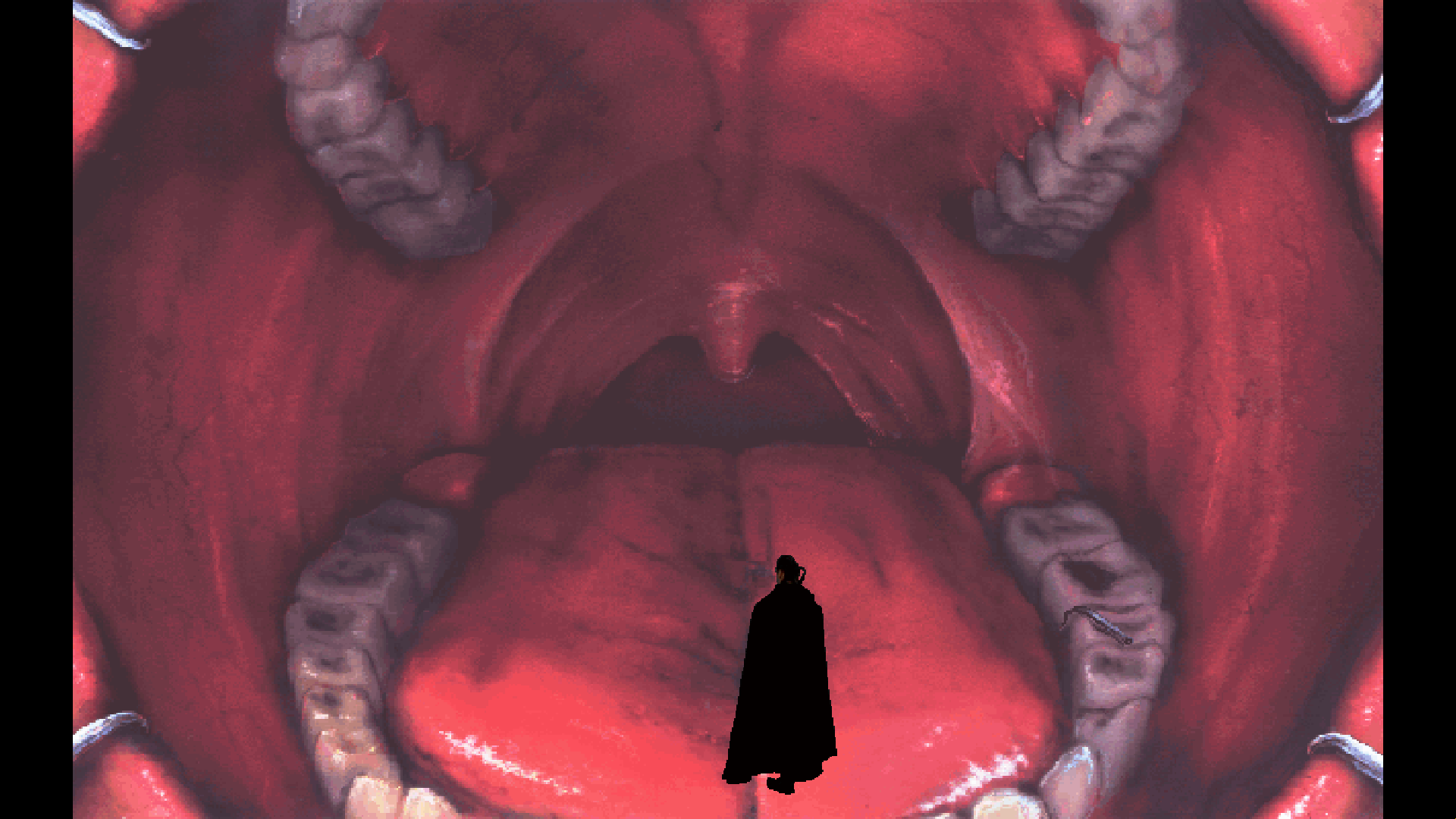

And front and center is the art—the stunning, painstakingly wrought backgrounds that evoke both a different era of game making and a different world. Booting up Noctropolis on Steam in 2020 is like time travel and an interactive lecture on old-school fantasy aesthetics in adventure games rolled into one.

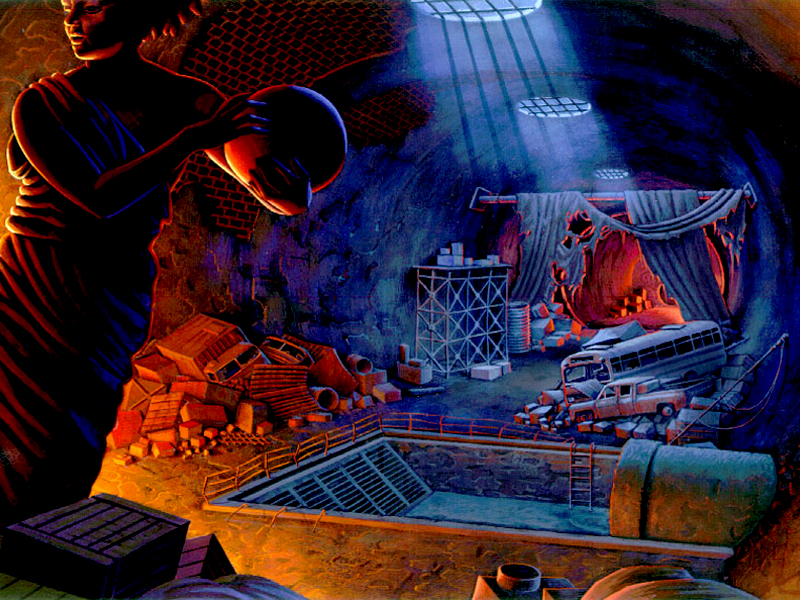

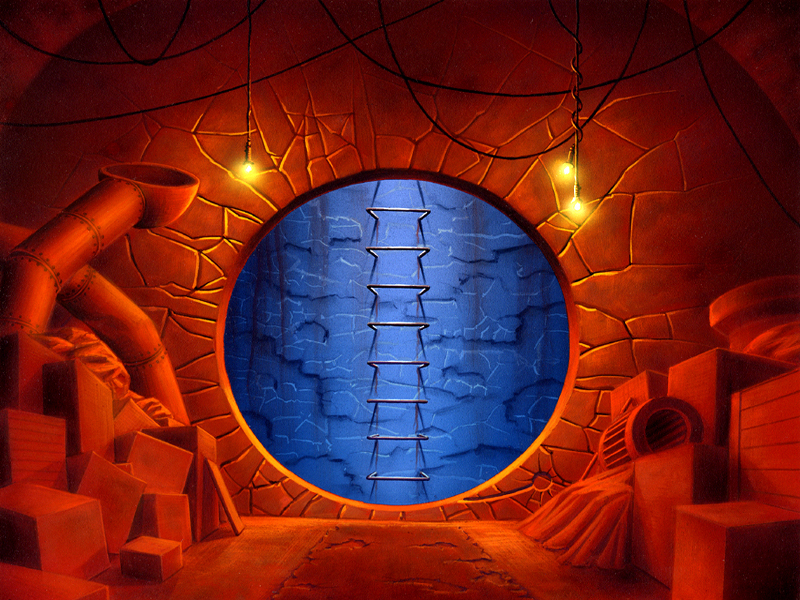

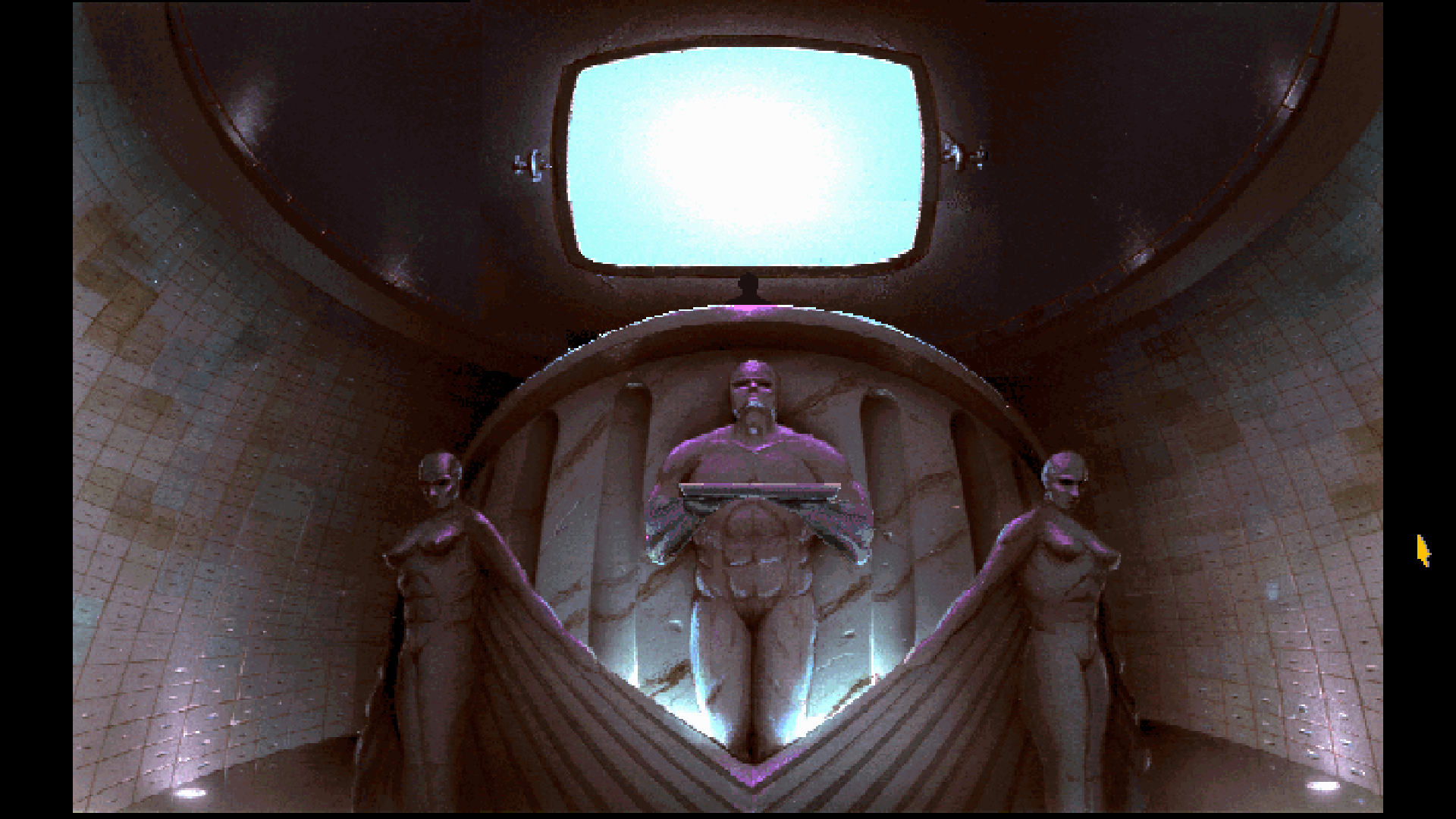

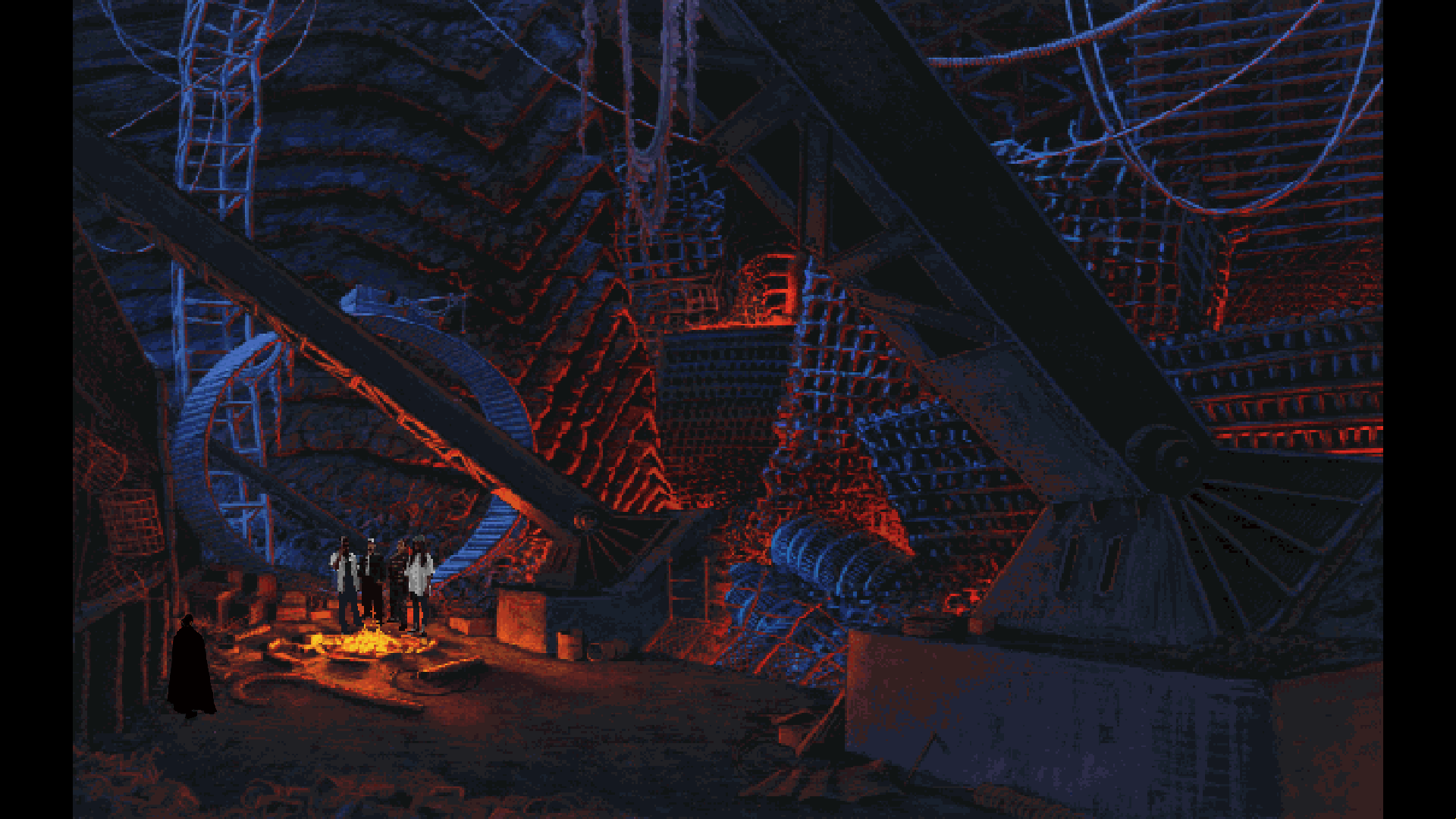

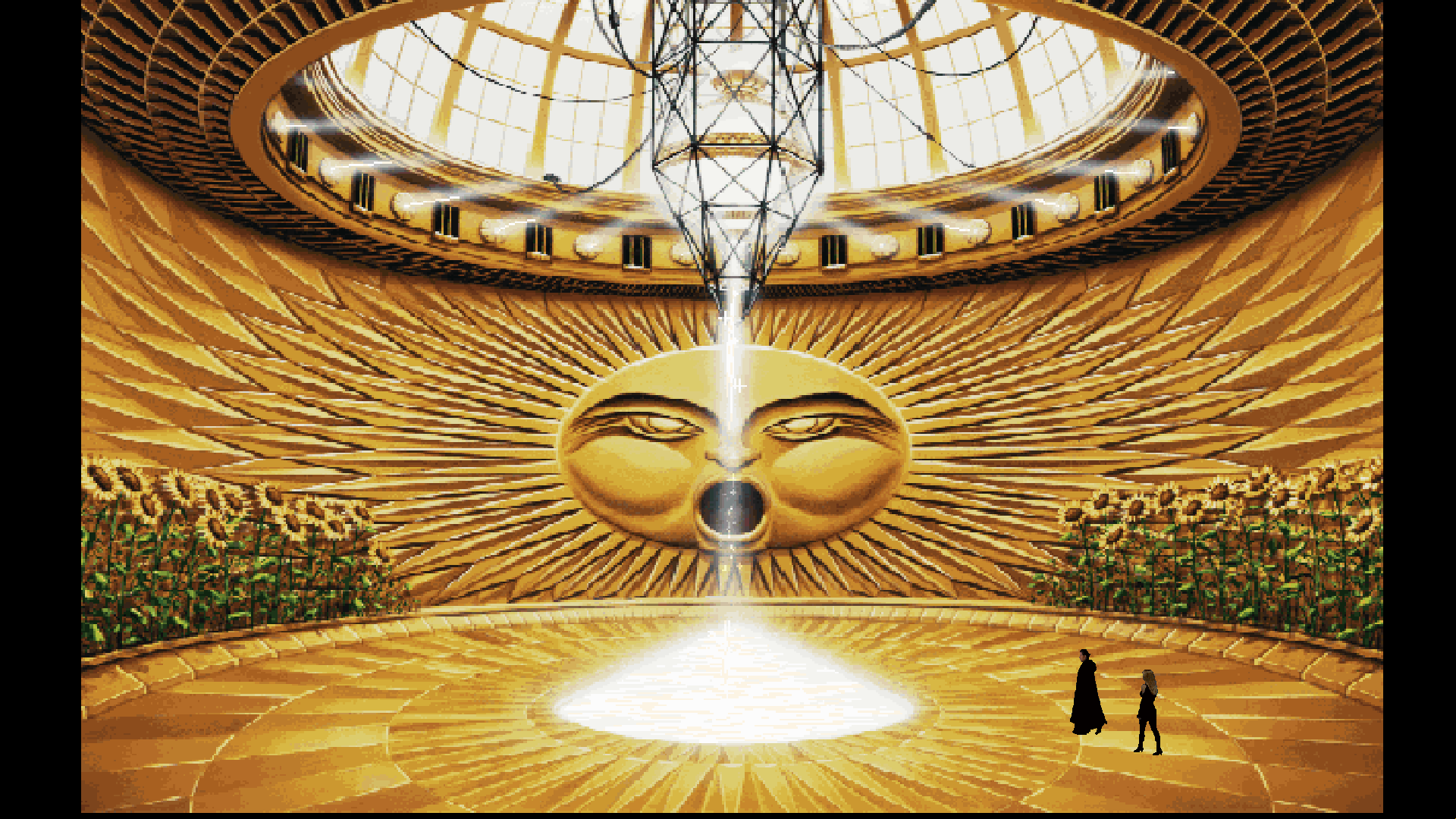

Playing it, I get little glimpses of its creators’ inspirations and influences. Standing below the colossal Promethean figures in the hall of records evokes the bureaucratic indifference in films like Brazil, right down to the bemused civil servant peering at you from a CRT screen. The cavernous underground below the opera house is rich with the promise of morlocks and other subterranean surprises—it's one of the game’s exquisitely hand-painted environments that hold the weight of a much bigger world. But perhaps Noctropolis' unorthodox production history is the very reason it became such a beautiful little weirdo in the first place.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Gone Hollyweird

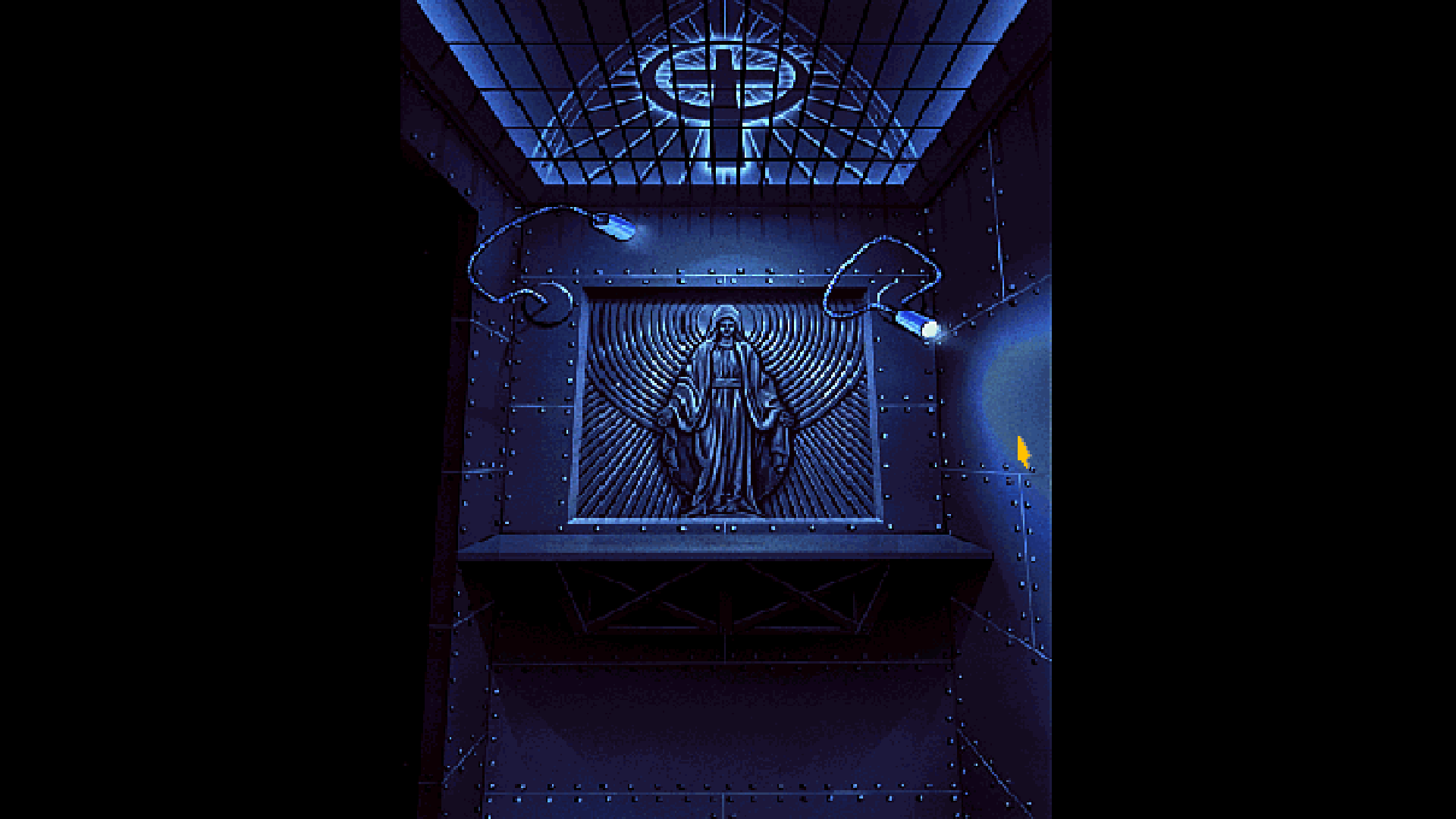

"The origin of Noctropolis was that it was kind of a comic property," explains Mitchell, who was also the game's creative director. "We couldn't afford any licensing, so we had to develop our own Batman knockoff." There's a whole prequel-style comic embedded in the game called Vigil's End, which introduces the player to a few of Noctropolis' villains, complete with a full page spread of a Watchmen-style clock. He describes the setting as an "alternate Gotham" inspired by the American architect Louis Sullivan, who mixed organic art nouveau details and ornamentation with modernist skyscrapers. From the titanic sculptures in the hall of records to the techno-catholic aesthetic of the church confession booth, each background in the game was a loving testament to the character of the city.

"The monolithic structures and statuary kind of took cues from Eastern European architecture that melded with this oppressive darkness that I thought gave the city personality," Mitchell says.

Like so many other cult games in the '90s, FMV was key to Noctropolis' identity. Erickson's experience working on the Tex Murphy game Mean Streets came in handy, and for Noctropolis, he wrote his own chromakeying software to work with the background art. "At that time, we didn't really have devices capable of capturing video, and so we developed software that would capture a frame of video one at a time and then composite them together into a video file," he says.

Soon after the Noctropolis team started shooting (on BetaCam, no less) in Mitchell and Erickson's home state of Utah, they were sent to Hollywood. "It was that same period of time where we decided to move from floppy disks to CD, and so the content that we were going to produce within the game expanded a lot," Erickson says. "So the decision was made to go to Hollywood and find some sort of professional resources, even though games were very new to Hollywood at the time. So even signing up the actors and those types of things... the Screen Actors Guild didn't have contracts that cover video games."

Mitchell remembers doing a reading at a hotel in Beverly Hills. Romance novel pin-up Fabio showed up to audition for the Darksheer role, and Erickson recalls meeting with cult B-list celebrities like the late Brandon Lee and martial arts icon Cynthia Rothrock. The team engaged Burman Industries for prosthetics—the Hollywood special effects company behind Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Goonies, and Teen Wolf (just to name a few). Costumes were designed by Mauricio Bizzarri, who worked on the Lynch film Lost Highway and the sitcom Who's the Boss? Mitchell even recalls working with Roger Pratt, who was director of photography on Batman (1989).

There were rehearsals, a hand-painted blue screen, and extra scriptwork for the numerous dialog paths in the game. It was the full analog Hollywood experience.

But after all of that, they ended up having to pack up and return to Utah to re-shoot the game footage. "It turned out that it wasn't fully sanctioned by Electronic Arts to do it in Hollywood, and so that caused some problems," Erickson explains. Both Mitchell and Erickson are, all these years later, surprisingly zen when recalling what most people might consider to be a huge setback. Erickson describes the do-over in Utah as a "bit of a waste of time" but concedes that they’d learned a lot from their brief time in Hollywood, even if they couldn’t use most of the footage they’d shot there.

Dark City

Both Erickson and Mitchell are clearly sentimental for the game, but now share reservations over its adult content

After returning to Utah, the developers re-cast Peter/Darksheer and partner Stiletto with local talent and Mitchell popped in to do a few small cameos. And they at least got to use some of the costumes that Mauricio Bizzarri made, keeping that small David Lynch connection intact.

There's a distinctly theatrical quality to the way Noctropolis' scenes are staged, in part due to artist Owen Richardson's background in theatre design. But the most memorable character in Noctropolis is undoubtedly the city itself. "When Noctropolis was developed, we didn't have 3D modeling software or great art tools, so we reverted to classical methods of producing fantasy art," Erickson says. Every background in the game was hand-painted on 8½ by 11-inch canvas by formally trained artists, including Richardson and Dave Butters. "We had to paint them small enough to fit on the bed scanner that we were using," Mitchell says. Coming from different backgrounds, everyone also had to agree on specific materials—gouache, acrylic, and some colored pencils.

When I ask Erickson where the original paintings are today, he isn't sure. "In '96, '97, Bethesda Softworks bought my company… so those were kind of part of the purchase," he explains. "I think Shaun and Owen probably kept a lot of the pictures they'd done."

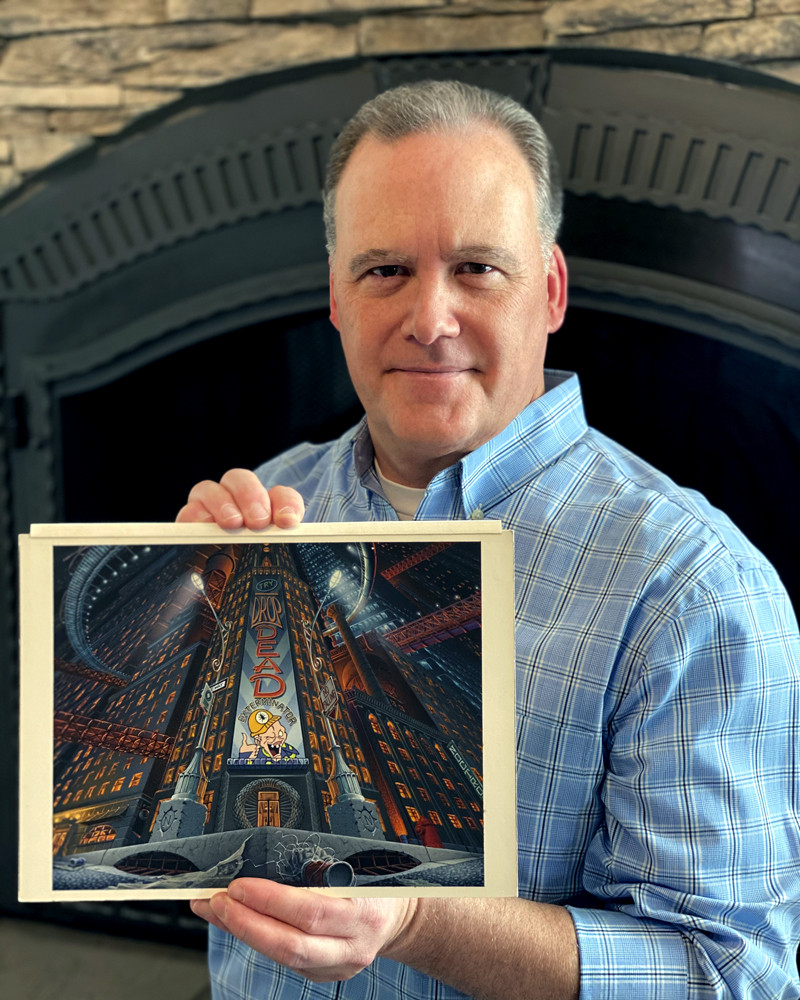

Sure enough, on a Zoom call with Mitchell, as soon as I asked about the paintings, he immediately held one up to the camera—the deep midnight-blue Noctropolis cover art, then the moody, dim interior of the confession booth. Each painting took around a week to produce. "I've had two or three guys from Europe reach out to me about the possibility of selling some of the artwork," he says, bemused. "It caught me by surprise because I just haven't been paying attention to gaming at all. It wasn't chump change that they were throwing around for this stuff." Mitchell left the industry around 2000 and now works in commercial graphic design and illustration. After consulting with his family, he decided to hang on to the originals.

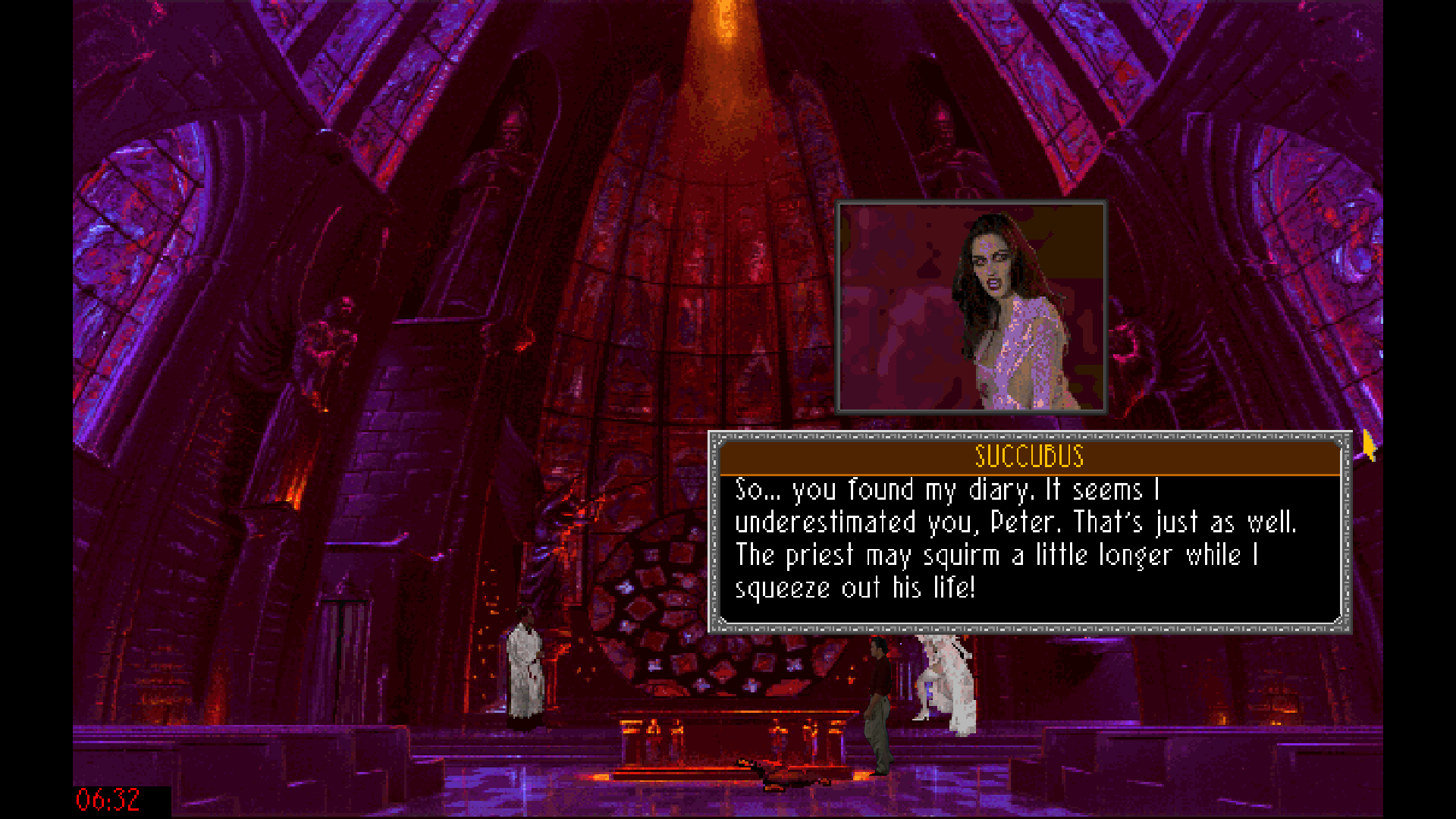

Both Erickson and Mitchell are clearly sentimental for the game, but now share similar reservations over its adult content. These are mostly brief moments of nudity, swearing, and an implied rape scene involving Grey and the villainess Succubus. According to Mitchell, that wasn't originally part of their plan. The adult angle had, in fact, been shoehorned in by EA. "They came back to us and said, 'can we maybe use this as a flagship adult-oriented product?'" remembers Mitchell.

When I point out that the story is geared for the male gaze, he agrees. "It would not fly today," he says. "If I had regrets about it, that would be a big one."

Erickson, too, is hesitant about how the adult aspect of the game turned out. "I think Noctropolis is one of the first games that had [nudity] in it, which I'm not necessarily proud of, but it was kind of a stretch for Electronic Arts for sure, to produce their first adult title," he reflects. "We had other ideas too, but just never got the opportunity to do it."

But Mitchell still dreams of keeping Noctropolis—his Noctropolis—alive in the form of an extended universe. Back then he'd already worked on a script for a sequel called Bedlam set in a similarly esoteric fantasy world. "What Darksheer was, was a kind of unholy marriage of 'hey we need a game idea' and 'comics are really cool,'" he says, going on to describe an entire system of natural phenomena that he'd come up with for the Darksheer mythology and a larger cosmology called The Glyph War Saga.

When I suggest a Kickstarter or a crowdfund, he says he hasn't thought about it. "[Noctropolis] was such a long time ago, but it's a property that keeps coming back to me," he says. "I like to pretend that I'm going to write someday… and every now and again, I'll reflect on it and regret that [those ideas] haven't been developed." I tell him there's still time to do it.

"There is," he says with a smile. "There's still time. I'm still breathing. It's exciting and terrifying at the same time, right? And I have all the freedom to make all the mistakes I want."

Alexis Ong is a freelance culture journalist based in Singapore, mostly focused on games, science fiction, weird tech, and internet culture. For PC Gamer Alexis has flexed her skills in internet archeology by profiling the original streamer and taking us back to 1997's groundbreaking all-women Quake tournament. When she can get away with it she spends her days writing about FMV games and point-and-click adventures, somehow ranking every single Sierra adventure and living to tell the tale.

In past lives Alexis has been a music journalist, a West Hollywood gym owner, and a professional TV watcher. You can find her work on other sites including The Verge, The Washington Post, Eurogamer and Tor.