The history of RPGs

Our comprehensive guide to PC RPGs spanning four decades—from Dungeon to The Witcher 3.

Computers and RPGs have always gone hand-in-hand. Even when the best adventurers could hope for visually was a few letters and numbers on a screen, what better way could there be to handle stats, die-rolls and complex calculations? Soon enough, though, computer RPGs were capable of doing much more.

The original PC RPGs—such as MUDs, or multi-user dungeons—appeared in the mid-70s. These weren’t for home computers, but mainframes, typically found in universities. They tended to be based on either Dungeons & Dragons, which itself launched in 1974, or be variously disguised takes on Tolkien. These included Dungeon, DND, Orthanc, and Oubliette. A few, such as Oubliette, had simple graphics, though most started out as just text or used ASCII’s standard set of text-mode graphics.

Despite the primitive technology, these games often offered surprising depth. Don Daglow’s Dungeon for instance, a 1975 D&D pastiche, offered control of an entire multiplayer party, mapping, NPCs with AI, line-of-sight-based combat, and both melee and ranged attacks. Moria, from the same year, served up wireframe graphics for its characters, and even featured rudimentary 3D views of its corridors. Small ones, with no detail, but let’s not forget that even Space Invaders wasn’t out yet!

THE QUEST BEGINS: 1975—1990

Bringing it home

For those outside universities, the genre really began around 1980. There had been games for home systems before that, including Temple of Apshai for the TRS-80 and Beneath Apple Manor for the Apple II, but few of them made real waves. 1980 saw the launch of Rogue, the first true dungeon crawl game, whose combination of randomly generated content and permadeath set the tone for today’s ‘roguelikes’. It would be a few more years before it and its clones would be available on home computers—the PC version landed in 1984—but the basics were here.

The most successful dungeon crawler of all time is, of course, Blizzard’s Diablo. But Rogue’s longest-lived descendent is arguably a much more interesting game—1987’s Nethack. Technically, it was based on a Rogue clone called, yes, Hack, but let’s not quibble. Nethack takes the basic dungeon crawling concept and adds several decades worth of development. Ever wondered if throwing a custard pie in a basilisk’s face will stop its petrifying stare? Nethack not only answers that question (it will), but also implements blindness if you get hit by a pie yourself, causes you to break your code if a vegan character eats one (seriously), and ensures the attack doesn’t count if you’re on a pacifist run (it does no damage, no matter your combat bonus). This level of detail lead to the saying “The Dev Team Thinks Of Everything”. Many versions are now available, from the original ASCII-based game to graphical overhauls like Vulture’s Eye. All are free, as a condition of the distribution licence.

As home computers became more popular over the ’80s, they began to take over—and many of the big names are still with us. Wizardry, for instance, launched in 1981, and the series ran until 2001. It used simple graphics and played out mostly using menus, in a way that most Western RPGs would soon try to move away from. However, its popularity in Japan led to it largely defining what that market thought an RPG was. Later games like Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest still follow its lead today, albeit with those systems endlessly refined and prettified. The Bard’s Tale followed in its footsteps in 1985, with three games, and returned last year courtesy of a $1.4 million Kickstarter.

Into the dungeon

Almost all RPGs of this era were fantasy based, though there were a few exceptions like Origin’s car-based Autoduel (1985, based on Steve Jackson Games’ Car Wars) and Starflight (1986), which swapped the traditional party for the crew of a spaceship on a quest to explore the universe and find out why the stars of the galaxy are flaring and destroying everything around. (It would later inspire the wonderful Star Control 2, as well as be one of the lynchpins for BioWare’s Mass Effect series.)

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

This shouldn’t, however, be much of a surprise. Fantasy worlds were easy to both produce and to understand—the difference between a shortsword and a broadsword being easy to parse. They also didn’t require much in the way of story, which was good, because they rarely offered much more than go forth and slay the Bad Dude/retrieve the Golden Whatever/rescue the Generic Princess. That wasn’t their fault, and it wasn’t simply that nobody wanted to tell stories. It was that doing so was difficult.

Most games of this era didn’t have the disk space for text. A 51⁄4 inch floppy disk held around 720KB of data. Its more compact successor, the 3 1⁄2 inch floppy, held up to 1.44MB. The more floppy disks a game needed, the more expensive it was to produce.

Most games of this era didn’t have the disk space for text. A 51⁄4 inch floppy disk held around 720KB of data. Its more compact successor, the 3 1⁄2 inch floppy, held about 1.44MB. The more floppy disks a game needed, the more expensive it was to produce. This is why, for example, the first Eye of the Beholder doesn’t have an ending sequence. One was planned, but it would have required an extra disk. The publisher said no. Instead, your reward for getting to the end was a quick burst of text going, more or less, ‘well done you won’ (the Amiga version retained the cinematic, so you can find it on YouTube now if you still feel ripped off ).

Some games found ways around this problem. Wasteland, for instance, released in 1987, came with a printed book that resembled a Choose Your Own Adventure. The idea was that when you reached a critical part, the game told you which paragraph to read. This saved space on the disks for more maps, graphics and other good stuff that RPGs really needed.

Most games got around it by shrugging and not worrying about it at all. Dungeon crawling was what people expected from these games, and dungeon crawling is what they got. 1987’s Dungeon Master, for instance, which offered a huge 3D viewing window on the dungeon (redrawn in chunks, step by step, not a fluid 3D engine), real-time combat, rune-based magic, and seemingly endless maps to explore. To put expectations into context, this was a time when anything 3D was impressive, and a game could make waves by letting you go outside—even when ‘outside’ meant painting the ceiling blue, replacing the dungeon walls with trees, and claiming it was a particularly dense forest.

The trick was still working by 1993’s Dungeon Master II: The Legend of Skullkeep and Westwood’s Lands of Lore, despite games like The Bard’s Tale long having experimented with ‘dungeons’ that were, say, the streets of a monster infested town, and even the UK TV show Knightmare, which went a couple of seasons inside computer-painted dungeons before ‘upgrading’ to location footage. The general rule was that dungeons could be first person, but overworlds were top down. We craved the day when that would change; when a company like Origin would announce Ultima Overworld to go along with its beloved, dungeon-exploring Underworld brand.

Dungeons and Dragons

Strangely, despite Dungeon & Dragons’ influence on the genre, the source made few waves at the time. This isn’t because there weren’t official games. Just about anyone who was anyone bid for the licence when owner TSR finally made it available in the mid-’80s, which was ultimately won by a company called Strategic Simulations Inc. This makes some sense. D&D started more as a wargame than a story-rich property, and wargames were what SSI did. Its most prominent attempt at an RPG was called Wizard’s Crown, which focused heavily on combat and character development mechanics. It had also dipped into the genre for the Phantasie series, and with Questron, a game so close to Ultima in design that Ultima’s creator, Richard Garriott, filed a suit against it.

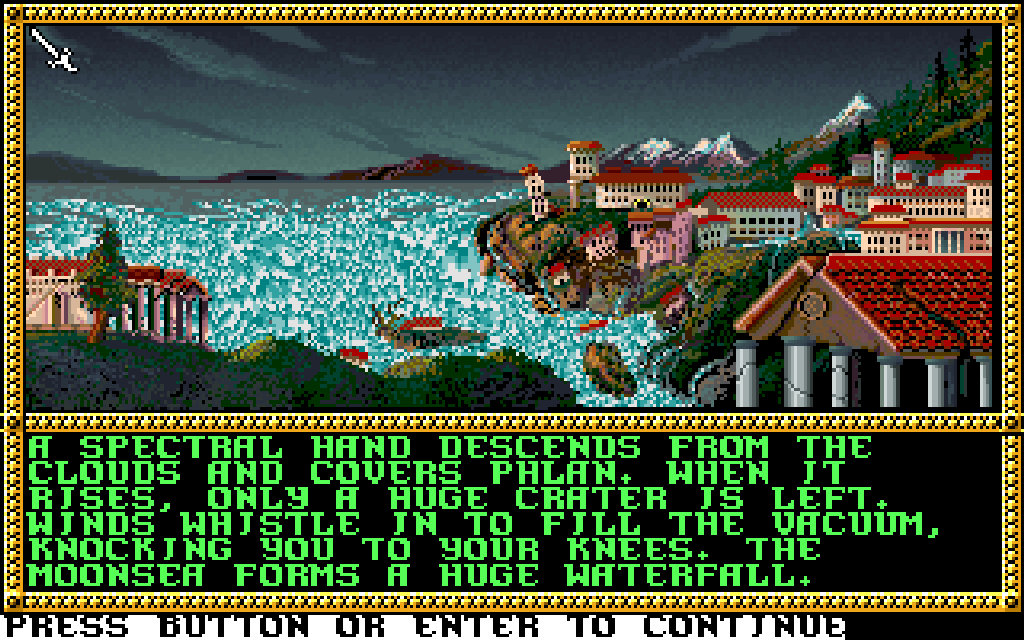

SSI’s later AD&D-based RPGs became known as ‘Gold Box’ games, based on, quite simply, the design of their boxes. Examples include Pool of Radiance and Death Knights of Krynn. They were popular, but rolled out on a production line, featuring top-down worlds, menu-based combat and very similar graphics—despite whether the world was fantasy or, as with Buck Rogers: Matrix Cubed, 25th century sci-fi. Still, the series was better received than many of the spin-offs that SSI published, like the side-scrolling Heroes of the Lance and its instant deathtraps. Until Baldur’s Gate came along, the Gold Box series was the defining D&D experience, despite a great many games coming out using its settings over the next ten years.

Of the others, one of the most interesting, though often forgotten, is Westwood Studios’ DragonStrike—a 3D dragon- hunting game that combined fantasy and early graphics technology to let you ride your own beast and take on others in action combat. It was billed as a Dragon Combat Simulator, and there’s no good reason why that didn’t become a genre.

Overall, while these games were popular at the time, they didn’t contribute a vast amount to the growing RPG genre. The source material was much better picked through for ideas, rather than full conversions. Gold Box games were popular, but quickly outstayed their welcome and are now best remembered as a thing of their time, while most others around them are best forgotten.

Ironically, many of the fondest remembered are the ones not from familiar parts of the D&D world (which in games, has tended to be Forgotten Realms and Greyhawk), like the Eastern themed Al-Qadim: The Genie’s Curse. The big exception is the aforementioned Eye of the Beholder, which cemented future Command & Conquer creator Westwood as a studio to watch.

The Ultima effect

Easily the most important series of the era was Richard ‘Lord British’ Garriott’s Ultima. The first, not including Garriott’s unrelated Akalabeth, came out in 1981, though it was re-coded and re-released five years later. It was an impressive game for the time, offering a top-down mode for exploring the world, a first-person wireframe dungeon crawling mode, and, for no particularly good reason except that he had space left on the disk, an outer space section where you shoot down TIE Fighters to be declared a ‘Space Ace’, and unlock a time machine that allows you to go back and kill the invulnerable villain Mondain before he has a chance to become so. This mixing of genres and throwing in random ‘cool’ stuff for the heck of it wasn’t unique to Ultima—Wizardry quickly developed a taste for merging fantasy and sci-fi—but this was still pretty surprising at the time.

Still, Ultima was simply another popular RPG until Ultima IV. Tabletop RPGs were taking a lot of flak from the moral minority at this point, up to and including being accused of promoting Satanism (magic, demons, all that good stuff ). PC RPGs were no different. Fed up with this, or so the story goes, Garriott decided to make Ultima IV about something unquestionably positive—the quest to become a better person. While there are monsters and dungeons, there’s no big cackling villain. Instead, winning means coming to embody the Eight Virtues of Truth, Honesty, Compassion, Justice, Sacrifice, Spirituality, Humility and Valor, to become the Avatar of Virtue; a symbol to look up to. This meant, for instance, not murdering peaceful creatures for their XP, or paying for goods with stolen gold.

This put Ultima on a fascinating path. Each new game not only offered a new engine, often stretching the limits of current PC power, but set about trying to tell a story that mattered. Having explored the Virtues in Ultima IV, Ultima V flips them. You return to Ultima’s world, Britannia, to find it under the control of a tyrant called Blackthorn, who is using the Virtues as weapons of moral absolutism. If you do not compassionately give half your income to charity, then you lose all of it. If you do not correctly support virtue, then you’re a heretic. It’s the Avatar’s job to depose him and the three Shadowlords who have perverted his thinking.

Ultima VI is arguably the cleverest of the set. This time you’re recalled to find Britannia under siege by an army of demonic looking ‘gargoyles’ who are trying to destroy the Shrines of Virtue. Everyone, including ‘wise’ Lord British (cue hollow laughter from every Ultima player) wants you to sally forth and beat up these monsters. In practice, though, the whole story is an allegory for racism and the importance of communication—the gargoyles revealed to not be an evil species, but one with their own moral codes and sense of honour. Most importantly, they have a valid grudge against both Britannia and the Avatar—the quest in Ultima IV having destroyed their homeworld. The next two games would pick up on the ease with which religion can be subverted, and explore the idea of the ends justifying the means—the Avatar stuck on a world that he ultimately has to sacrifice in order to return home and deal with a bigger threat.

Ultima raised the bar of the types of stories RPGs could tell, and proved they could be about something. It didn’t hurt that, along with this, the series contributed heavily to the growing genre—advancing what was possible with every new game. Ultima VII in particular stood as proof that an RPG could look gorgeous without sacrificing detail, (as long as you could actually run it.) It brought dialogue trees and day/night NPC schedules to the series, and its simulation elements have yet to truly be bettered. Players could shear sheep, spin the wool into yarn and then weave it into cloth. Or combine flour and water to make dough, then cook it to make bread. The series proper sadly ended in shame in 1999, with Ultima IX: Ascension, but Garriott is currently working on what he hopes to be a return to the series’ high points—Shroud of the Avatar, coming out soon.

Bonus XP

By necessity, I’m skipping over many games here—some famous, some not. By the end of the ’80s, though, we were firmly in an age of innovation, with many obscure games that deserve a quick call-out. Drakkhen, for instance, released in 1989, offered one of the first fully explorable, real-time 3D worlds. It was a simple one, full of deathtraps, random encounters and poorly translated dialogue that made it tough to tell what was actually going on. But it still did it.

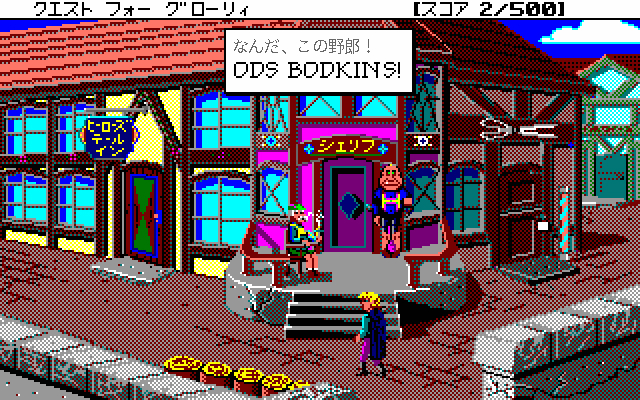

Then there was Sierra’s Hero’s Quest, also in 1989, which merged adventure gaming with RPGs to great effect. Unfortunately a licensing issue meant a swift rename to its better known title, Quest for Glory. They’re more on the adventure side, and so I won’t be covering them in any detail, but they have enough RPG in their DNA to still be worth a mention. There was also Worlds of Ultima, which took the Ultima VI engine and used it to create two spin-off games. The first, The Savage Empire, took place in a Doc Savage-style jungle world filled with tribes drawn from various historical periods. The second, Worlds of Adventure 2: Martian Dreams, was set on Victorian version of Mars. World of Ultima was going to finish with an Arthurian tale for good measure, had Origin not decided to focus on its core series instead of dabbling in spin-offs.

In short, after the first 10 years or so on home PCs, RPGs still had to get over the hump of being complicated, often very hard, and geeky, even by gaming standards, but they’d established themselves as a genre to be reckoned with. All they needed was the technology to turn their worlds from things to imagine into places we could genuinely explore. It was about to arrive. Or so we thought.

Continue to page 2 of our history of RPGs where we explore the genre between 1991—1997.