Remembering Planet of Death, Ubisoft's post-apocalyptic racer

POD was one of the first pieces of media to make me truly consider the end times.

This article first appeared in PC Gamer magazine issue 360 in August 2021, as part of our 'Reinstall' series. Every month we load up a beloved classic—and find out whether it holds up to our modern gaming sensibilities.

Created as a graphical showcase, POD was an elaborate tech demo, a grim science fiction racing game that came baked in with a lot of computers using Intel Pentium or Pentium II MMX processors, and some AMD K6 systems. Back in 1997, it was one of the best-looking games you could play.

If you grew up in the ’90s and knew anyone into PC gaming, it was probably on their computer at some point. POD was one of those cultural artifacts that huge swaths of the public were involuntarily introduced to, like when They Might Be Giants’ song “Older” came packed in with RealPlayer on so many early ’00s HP prebuilts, or Chip’s Challenge in a Windows 3.1 entertainment bundle. Ubisoft later released a retail version, but POD was birthed from the same tradition as Norton Antivirus and McAfee: OEM software, baby.

Following one of the most essential PC gaming myth arcs, my uncle had a gaming PC in his basement, nested in one of those huge faux-mahogany desks that shouldn’t have been able to fit through the door. The CRT was too big for its available surface area and audibly hummed for about two minutes after it was powered off, the keyboard stuffed into a wide drawer not meant for keyboards resting on a soldier’s stew of thumbtacks, erasers, pencils, and pennies. A very domestic strain of cosmic horror.

But the dust illuminated by a tiny window (a fi recode violation for sure) only elevated POD’s grimy, nihilistic excuse for racing. I almost felt like a two-faced booker, watching the races from some remote warehouse location. The only thing missing was a cigar and a frosty mug of spoog or grumm, or whatever future wasteland beer alternative existed in POD’s universe. The whole thing foretold my obsession with Thumper, because POD was the first time I remember playing a game purely for the bad vibes.

Fun guys

It’s the distant future on a planet very creatively named Io. Humanity builds a bunch of weird, bulky skyscrapers as fast as possible, eventually covering what looks like the entire surface area of the planet, all in the name of job creation. A capitalist critique is incoming, but no, humanity isn’t its own undoing. This is a story about nature getting its revenge. And yes, it’s a racing game, too, I promise.

A super fungus creeps out of the planet’s surface and feasts on all those wacky skyscrapers—and mankind too, for dessert. People dip out on ships in droves until there’s just one space taxi left. Naturally, every remaining human alive calmly agrees to conceptualize, plan, and enact an elaborate mid-apocalypse racing circuit for the final seat. The whole story is laid out in this elaborate, four-minute intro cutscene, where the music moves from synthy sci-fi to electric guitar power ballad. We go to space, see civilisations rise and fall, and cars shaped like bird feet crash into skyscrapers. At the time, it blew my head off. Today, it’s incredibly dumb, but so are my sensibilities. God, I love POD.

Well, I love POD as I remember POD. I remember the most beautiful palette of greys and browns and greens and oranges streaking together I’d ever seen in a game. Beltane is a sprint down the city freeway, a dour purple sky in contrast with the yellow glow of the last remaining skyscrapers with power. I love the surreal hillsides of Pompeii with its roads stretching out at impossible angles into the distance. Plant 21 is what Bowser’s Castle would look like if it was set in an abandoned industrial shipyard, and if Bowser was a 50-year-old mob boss, I suppose. Then there’s Roc, which imagines the art of HR Giger as a river, a psychosexual racetrack of spires and jet black organic-seeming pipes and machinery forming hypnotic, pulsing patterns on every surface. If you’ve ever wanted a track to make you horny and sad, POD’s got you. There’s so much more to see, too. With over 30 tracks in the final version, it’s worth at least checking out the sights in each.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Pod is preserved so well in my memories because of its simple premise

I remember cars that felt heavy and powerful, and that every impact with another vehicle resounded with a deep impact that sold the fantasy of driving a future tank cobbled together with slabs of rusted, corrugated metal and gas line pipes refitted for the express purpose of going fast. I remember an overwhelming sense of menace and dread from the odd scenery running beside every track, and how the sharp angles of every car spoke to some alien knowledge of aerodynamics and technology. My mum’s ’97 Astro van looked even more like a cinder block in comparison—though, to be fair, it was very grey and very rectangular.

POD was one of the first pieces of media to make me truly consider the end times, and it was all filtered through The Rule of Cool. Ubisoft made an unnerving, sickly thing for my simple eight-year-old mind, whose only other conceptual playdates with the end of civilisation were limited to the dirt towns I made for the ants in the backyard. Even so, I couldn’t look away. I didn’t want to.

The truth is that, even though POD is easy to find and run through an updated version on GOG.com, it has aged far worse than I expected. If you play it anyway, find the POD entry on PCGamingWiki.com and install the PodHacks patch for some bug fixes and more flexibility with the forced 800x600 resolution, which can cause some issues on dual-screen setups. There’s a widescreen hack too, though it breaks some of the skyboxes which I’d argue are The Point of POD. If you’re one of these smug post-gamers like myself, maybe you can appreciate the game falling apart in front of your eyes. I do, but I don’t go around telling people about it. Can you imagine being that insecure?

Pod racing

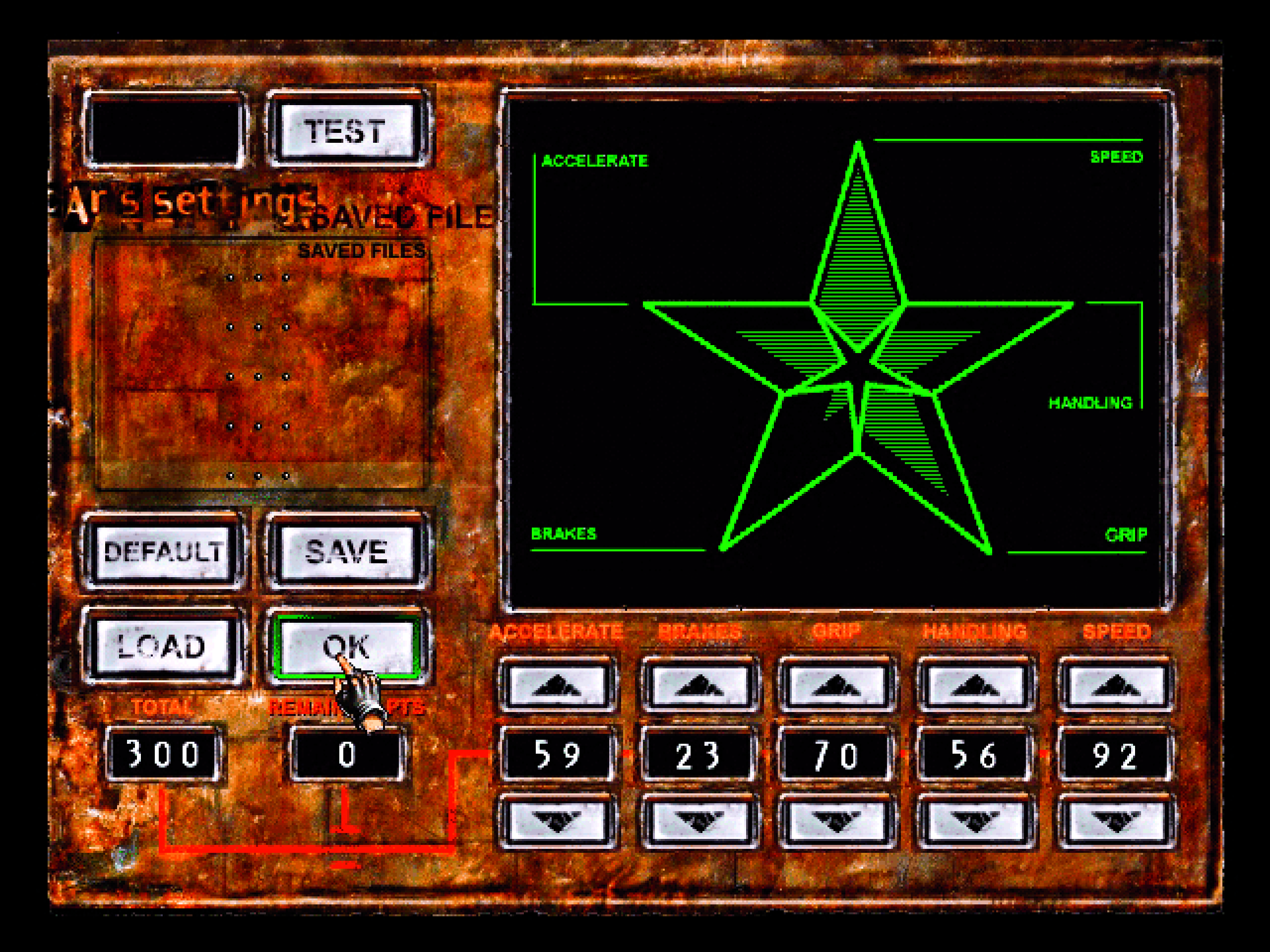

My hands are too big for the simple arrow-key controls, and cramped up after just a few races. Handling is awful too, with cars accelerating wildly from short taps of the keys. A seemingly deep stat system allows you to reallocate 300 points wherever you like, into braking, acceleration, turning, and the like, though it doesn’t add up to much in action. POD has a fixed meta, favouring speed and turning, so long as you’ve got the requisite track knowledge. You either get to know the tracks like the alleys of your hometown, or die.

POD plays into early racing game design, where success was primarily based on extremely granular muscle memory, both in track memorisation and turn acceleration. Staying on the course is the primary challenge. Avoiding the walls is the fun. Game design really has come a very long way since POD’s days.

But POD is so, so touchy and the tracks so narrow and crowded that you spend a lot of time bouncing off the railings and other cars. I’m reminded of F-Zero, the way you can get into a flow state of perfect key presses and depresses once you’ve built up enough familiarity with a track, but without the same sense of speed and far more abruptly windy, punishing turns. And if you have POD’s damage system turned on, getting through a single race is a monumental, frustrating challenge.

I respect the implementation of a damage system, especially to sell the fi ction that these are shitty, rusted carapaces barely holding together – but the cars break down faster than I do looking at myself in the mirror. The landscape of my brain just isn’t built for this kind of skeletal trial and error anymore. I am old now and have important stuff to do, like compulsively checking my phone and worrying for no reason.

Pod was one of the first pieces of media to make me consider the end times.

One of these clips in my mind: murky brown skyscrapers on the horizon, a skybox like vomit, and my wheels sailing through the air over the main track below. I found a shortcut for the very first time in a racing game. I remember recognising them in later racing games, like Star Wars Episode I: Racer, where you had to not only make sharp, quick turns but flip your racer horizontally to squeeze through a tiny crevasse; or in Lego Racers, where an early track on an alien planet opens up a shortcut based on secret sequence of coloured gates you drive through.

Maybe Lego Racer’s puzzle-solving and Episode I: Racer’s needle-threading ruined me. POD’s shortcuts are boring and bad, 90-degree turns into tighter hallways with the occasional ramp as a treat that barely saves time. I’m grateful to POD for teaching me to pay attention, but in retrospect I feel a little cheated. Time is mean, man. POD is preserved so well in my memories because of its simple premise, and for how evocative its courses and cars are of a world with an accelerated history in ruin, all without ever explicitly detailing the goings-on of the world. It might’ve been my first ever apocalyptic setting, and more than anything I remember the mood POD put me in.

Tune in

Music was a major component, with a soundtrack put together by Daniel Masson of Rayman 2 fame. The score isn’t very long, but it works on repeat. As you race, the same looping 15 minutes of trance play out, a steady journey from sparse celestial arrangements to more percussive industrial movements that wouldn’t sound out of place in the original Half-Life. If you do play, I recommend turning down the SFX and juicing the music. Get rid of the other racers too and POD basically transforms into poor man’s Thumper. Even though it’s lacking the syncopation, it’s a more immediately hypnotic way to play, at least before the arrow-key cramps ruin your hand for the day. If that’s too much, the 15-minute MP3 is right there for the taking in the POD game directory. Add that to your favourite playlist in WinAmp, throw on a good visualiser, do some future post- apocalyptic sci-fi drugs that don’t exist, and shake out those cramps.

This might be the first Reinstall where I’ve actively ruined a game for myself, where I’ve written over strong childhood memories with the sad impatience only 31 years of adequately comfortable living can produce. But like the ending cutscene of POD—in which you barely escape the planet before it’s completely enveloped in fungus and ride away on the final ship as Io blossoms, the literal crust of an entire planet splitting and flowering, farting out globules of pollen into the cosmos—it’s OK to move on. Something else will take its place, like a huge-ass space flower, or more voracious evil colonisers, or Mario Kart: Double Dash or whatever. I don’t know anymore.

James is stuck in an endless loop, playing the Dark Souls games on repeat until Elden Ring and Silksong set him free. He's a truffle pig for indie horror and weird FPS games too, seeking out games that actively hurt to play. Otherwise he's wandering Austin, identifying mushrooms and doodling grackles.