Mail trucks and millions of dollars: how shareware transformed PC gaming forever

We can thank floppy disks in Ziploc bags for the FPS genre as we know it.

The year is 1982. The internet won't exist for several months yet, and the Web won't go World Wide for another decade. But if you send a formatted floppy disk to a man named Andrew Fluegelman, he'll pop a copy of his communications program PC-Talk on it and send it back free of charge. If you like it, you can make further copies for your friends. In the event you really like it, you can send Fluegelman $25. "If you order the program and are disappointed," wrote PC Mag in its August-October 1982 issue, "you've lost nothing but a stamped, self-addressed envelope."

By the end of the '80s, Apogee's Scott Miller was making $100,000 a year through cheques showing up in his mailbox

Fluegelman characterised this model as "an experiment in economics more than altruism", and sure enough, it soon started making people rich. Free distribution gave software developers such enormous reach long before internet downloads that even voluntary payments from a fraction of their users resulted in huge profits. They settled on a name: shareware.

Apogee founder Scott Miller grew up in a household with a former NASA engineer for a dad and an IBM PC packed with shareware. "My father had even sent a couple of guys some money," he says. "So it was on my mind." By the mid-80s, the younger Miller was coding videogames in his spare time at college and making them available much the way Fluegelman had.

"I had written some text adventure games in the style of Infocom, released those into shareware and asked people to send me money," he says. "And it just was not working out at all. I wasn't making anything worth talking about."

What Miller was missing was an enticement—a way to lure players into payment, without giving away a whole product. In 1987 he put out a trilogy of fantasy roguelikes named Kroz: The first, a 25-level game, was released for free, but the second and third parts cost $15 each. "That was the magic trick that worked," he says. "No one else was doing that. I immediately wrote another three Kroz games and did the same thing with those."

By the end of the decade, Miller was making $100,000 a year through cheques showing up in his mailbox. He quit his day job and began reaching out to other game authors through pre-internet services like BBSes and CompuServe. One was Todd Replogle, an "amazing, amazing talent" who dreamed up Duke Nukem with Miller and worked as a programmer on the series from its origin as a platformer through to its final, 3D form.

Another was John Romero. At the time, Romero and the team that would become id Software were pumping out a new game every month for Softdisk, a company that promised subscribers 12 original games over the course of a year for a total of $89.95.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

John Carmack had blown Miller away with his demo of a smooth-scrolling platformer on the PC—a feat akin to distilling Super Mario in his garage (id literally did that, too). But the nascent id Software wasn't convinced of the merits of shareware. "If you want us to make a game for you," they told Miller, "you gotta pay us $2,000 to do it." Miller practically punched the air, knowing he would have gladly paid 10 times that amount to publish id's first game.

Keen dreams

The postal service actually sent an empty truck to our office, just to load up all the packages and everything we were sending out

Scott Miller

In December of 1990, Miller uploaded Commander Keen's first episode to bulletin board systems that served as file sharing hosts. For $30, players could order the two follow-up episodes on floppy disks in Ziploc bags. And they did. In droves. By the end of the month, Miller had sent Romero and co. $10,000 in royalties.

The next cheque, in January, was for $25,000. "It just grew from there," Miller says. "At that point, they were completely sold on the whole idea of shareware."

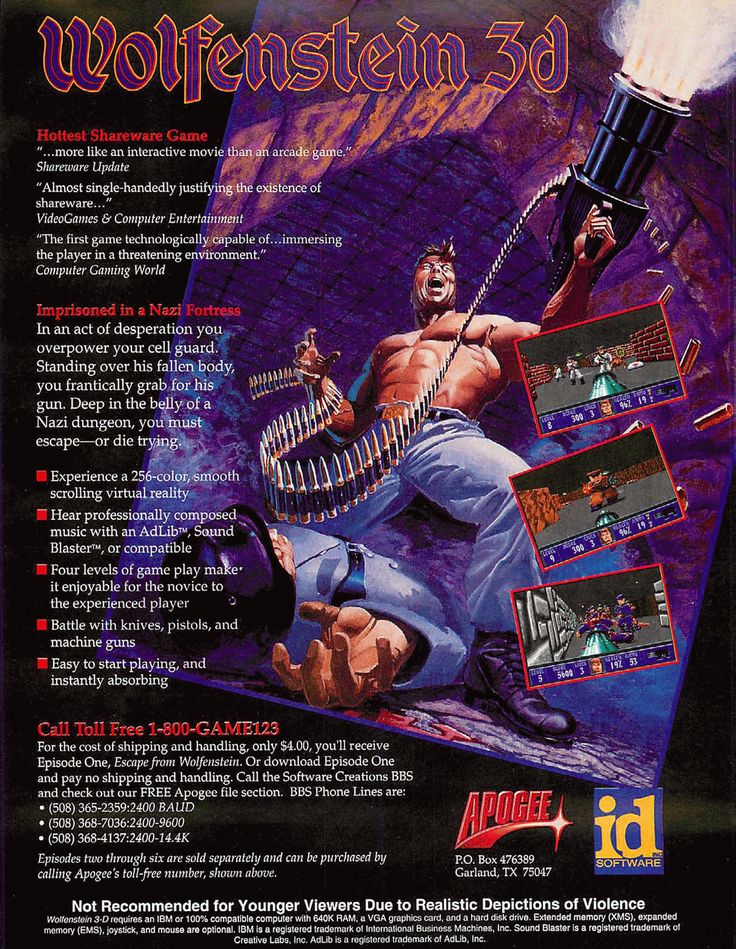

Yet shareware wasn't solely a pact between the publisher, developer and consumer. It required the cooperation of the postal service, which was completely fascinated by this new mail phenomenon—taken to a new level by the launch of Wolfenstein 3D. "They actually sent an empty truck to our office, just to load up all the packages and everything we were sending out," Miller says. "We got really close to them, and also developed a really good relationship with our local printer for all the labels and everything. Early on, Apogee developed more as an order-taking company."

Only in the months after Wolfenstein 3D, as id Software's star continued to rise, did Apogee move into internal development. While the company was still working with several shareware creators, Miller knew that Romero and Carmack would want to break off on their own, and so asked former id Software designer Tom Hall to lead work on Rise of the Triad, a new Apogee FPS that would keep the company's mail order staff and infrastructure busy.

"It actually started off as a Wolfenstein sequel," Miller says. "Wolfenstein 3D: Rise of the Triad. That's why it has the whole military angle. But about 10 months into development we got a call from John Romero, who said, 'You know, we really don't want another Wolfenstein game coming out. We'll let you continue to use the engine, but you can't call it Wolfenstein anymore.'

"Their worry was that it was going to be released too close to their coming game, Doom, and they didn't want the competition."

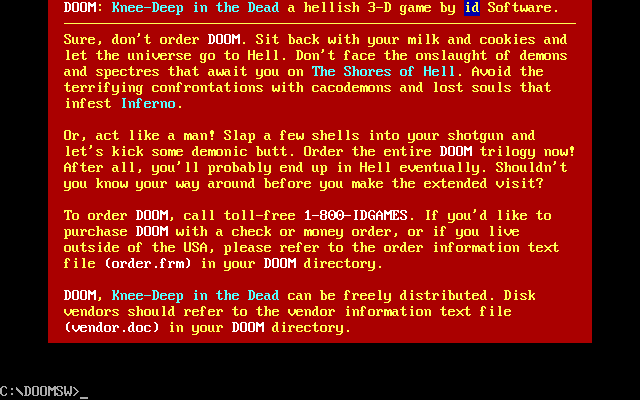

Doom ended up sweeping away any and all competition. Shareware players bought 1,154,541 copies, placing it among the best-selling games of the '90s. In the process, Doom brought shareware to the attention of an enormous audience, and inextricably associated the model with the budding FPS genre. By then shooters were becoming too large and complicated to be developed as trilogies like Kroz and Commander Keen, so the convention was to release a generous set of taster levels for free. If players wanted more, they could mail in for the rest.

Shadow war

Shareware's sales structure couldn't help but have an impact on the shape of a game itself, tempting developers to stick the finest levels upfront to make the best possible impression. At Apogee, though, development tended not to pan out that way. "We gave a lot of thought to maybe developing the middle episode first," Miller says. "And once we become experts in making our own game, then we can do the first episode, make sure we get it right. But it never worked out, we always made the first episode first. For a lot of our games, the later episodes were the better ones because of that."

Of course, many players never saw those later, more refined episodes. For Rocksteady web developer Jason Burt-D'Arcy, who was a young teen living in the small Southampton suburb of Netley Abbey in 1994, access to free games was a revelation. Wolfenstein, Doom, Heretic, Duke Nukem 3D, Shadow Warrior, Rise of the Triad, Descent, Quake—he played them all. Up until they asked for a cheque, that is.

"You got some levels, a bunch of weapons and a cool boss to kill at the end," he says. "Because these games, Doom in particular, were so good you would just go again. It had scaling difficulty and loads of hidden things so there was still plenty to do. I never felt like I wanted more because I'd been given so much already."

By the late '90s shareware had shaken the traditional industry to its core

At the time Miller reckoned that Apogee's games were in some cases reaching tens of millions of people: "My estimate was that about one or two in every 100 people that would download a game would end up sending us money for it," he says. "Nowadays, ordering on Steam is just pressing a button. Back then you had to pick up the phone and have your credit card ready or write a cheque. There was a lot more friction."

There were additional barriers for international players, too. Apogee established a worldwide network of partner distribution companies and published lists of local dealers that could be accessed via the menus of its games. Yet even so, some customers were put off by US-centric advertising in an age when the oceans between continents felt wider. "I remember taking one look at the purchase information and it was 0800 numbers and dollar signs," Burt-D'Arcy says. "I wouldn't have known where to start."

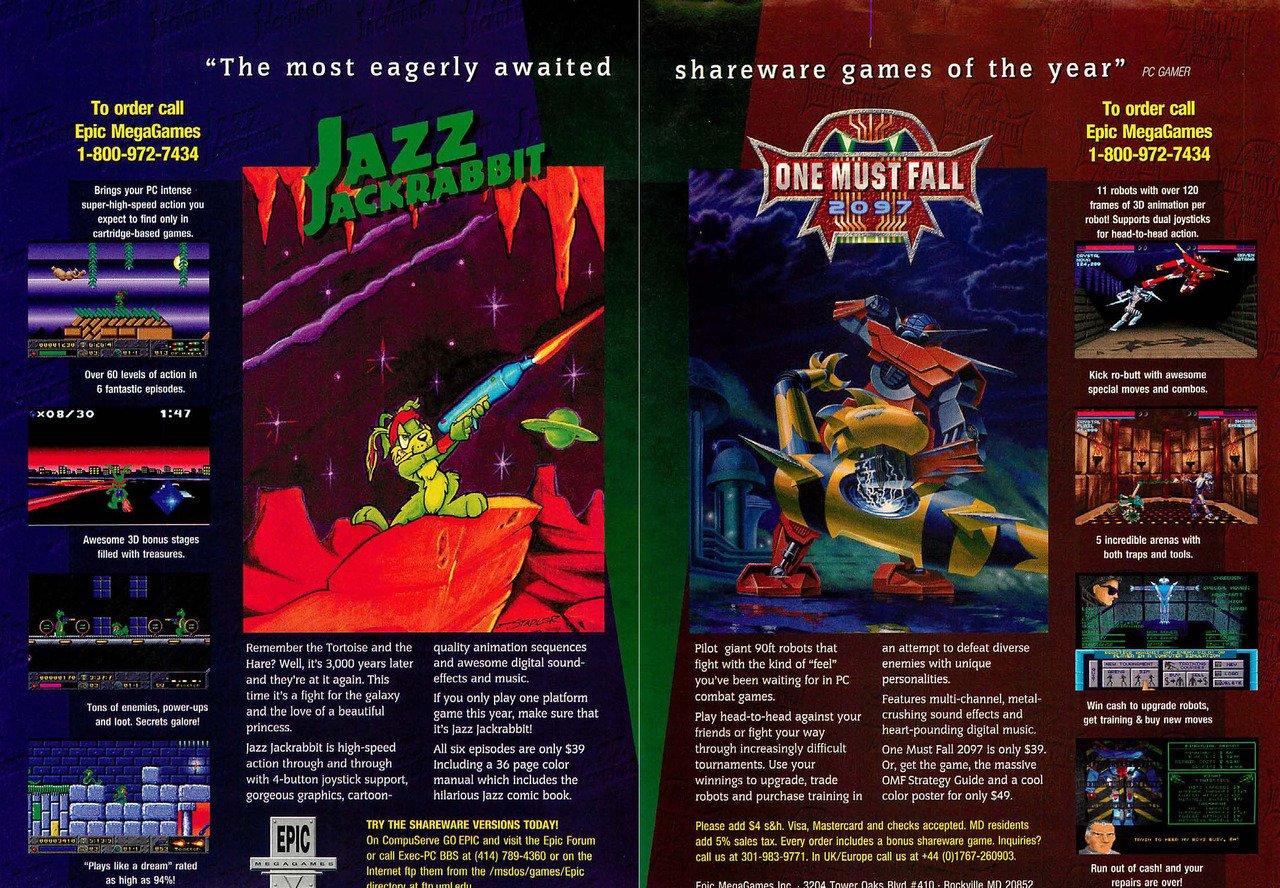

Those borders came down with the internet, and by the late '90s shareware had made enormous successes of not just Apogee but other lasting companies like Epic Games. It had shaken the traditional industry to its core. "I remember hearing a story that there was a board meeting at Electronic Arts," Miller says. “And one of the top people slammed Wolfenstein 3D on the table and said, ‘How are these guys beating us? How can some little company out of nowhere be making better games than us?’”

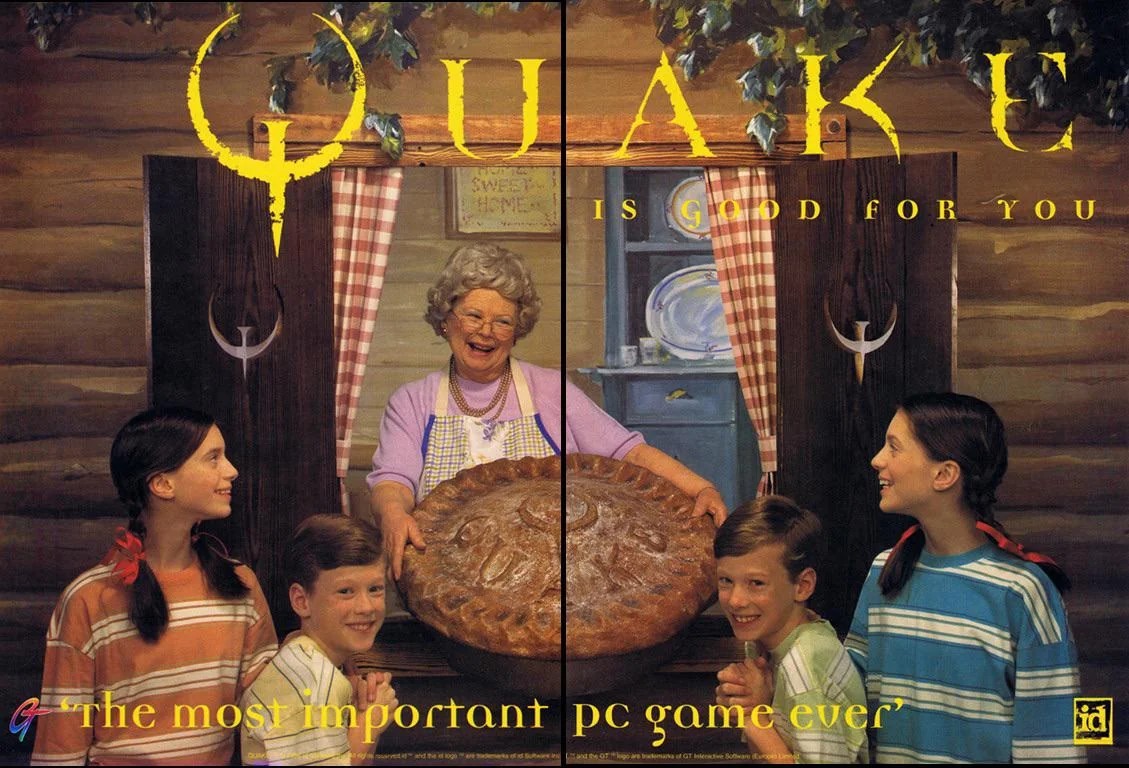

By 1996, Quake’s shareware edition was the sixth-best-selling game of the year in the US.

But in the end, the internet brought down shareware too. Over time it became possible, and then trivial, to download full games online, making mail order the preserve of lavish collector's editions.

Sharewhere?

While the idea of episodic gaming still appeals to developers, it's often proven to be a poor fit for the volatile and unpredictable nature of game production. Valve abandoned Half-Life 2's expansion episodes after two entries stretched across multiple years. And although Hitman's World of Assassination trilogy is now a huge commercial success, that wasn't true while its first levels were releasing one-by-one—most players prefer to wait for a whole, finished product before investing.

The original Telltale Games remains the biggest name in episodic gaming—yet financial insecurity and the crunch associated with an aggressive release schedule saw the company unravel in sad, spectacular fashion back in 2018.

So where does the spirit of shareware live in PC gaming today? Not with free-to-play, according to Miller. "There's always some sort of grinding element that you can somewhat bypass if you pay, which I'm just not a fan of at all," he says. "We never had anything like that. There were no throttle [points] in the shareware releases of our games."

Miller's more keen on demos, which have seen a reemergence in recent years thanks to both the rising cost of full-price games and high-profile events like Steam Next Fest. "They're super important for game developers to be doing nowadays," he says. "Even more than early access. Because what you're trying to do with a demo is just get your game out there, allow people to download it for free, and once again get hooked to the point that they wishlist it."

Crucially, demos are a way to spread word-of-mouth without exposing an unfinished game to Steam user reviews. "It's a way to have the public help you playtest, get great feedback from them and modify your game as necessary," Miller says. "At most you want to give away about 25-to-30% as your demo, which is what we did back in the shareware days." It's a model the modern-day Apogee will be following for all its upcoming releases.

As an adult, Burt-D'Arcy works as a web developer, and sees something like a shareware spirit in his field. "The sheer amount of code that is written and given away for free is completely mind blowing," he says. "So much of the systems that run our daily lives is [built] on code that people wrote because they love making things."

Yet in games? "I don't think there is anything really like it anymore," he says. "Shareware was about faith. Faith in your own ability to make something good, and faith in people to respect and respond to that." It wasn't altruism, as Fluegelman pointed out in the beginning. But it was rooted in something pure—an optimistic belief that generosity would be rewarded in kind.

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.