Wonderful WASD: Legend of Grimrock and the value of easy input

I like most of Legend of Grimrock's impenetrable puzzles. I like the way it makes consumables scarce. I like its shadows. I like the way its spell system feels like Simon. I don't like its damn electric bats . I like that it's the most insulated I've felt in a game space since BioShock.

But an under-mentioned thing I love about it is that I can play it mostly one-handed. You know, while swirling a tumbler of Mountain Dew, or something.

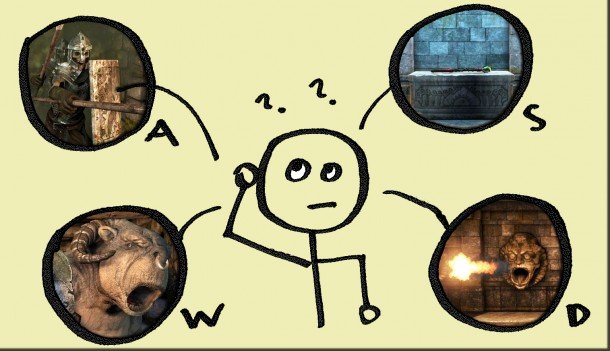

This is a pretty basic observation. But I think it's a valuable one—it's a joy to touch a control scheme that mirrors the design of the game space itself. In one way, WASD is the intersection of two axes, divided into four units. Grimrock is played on two axes that you traverse by stepping north, south, east or west in one-unit increments. As physical metaphors go, it's 1:1.

http://youtu.be/sYbTgRBMiKM

That scheme makes piloting Grimrock on WASD (using Q and E to rotate) feel like a cozy joystick. But it also helps express Grimrock's guiding theme of helplessness. The literal tunnel vision of the first-person camera—you can only view one quadrant at a time while moving—represents the eyes of a quartet of prisoners, all thrown into a dungeon-tower designed to kill you and break your mind. You're powerless, and you have to play by the crypt's cryptic rules to escape.

Having a maximum of four movement options at any time those options can be meaningfully restricted or taken away. It's a system that creates incidental verbs that reinforce that guiding feeling of helplessness: players can be blocked, attacked from behind, trapped, surprised, surrounded.

It also asks the player to visualize areas of the game space that they can't see. At a given moment, your brain might retain: “If I move left onto that trap door, I'm dead. There's a wall to my right. There's a skeleton in front of me, I can't go that way. Behind me is clear.” It's a set of simple, consistent rules built for problem solving; some rooms draw on your spatial awareness directly with puzzles that ask you to move in a specific pattern in order to pass.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

If Grimrock had foregone the quaternary style of movement of Dungeon Master , its spiritual predecessor, this mental process of elimination wouldn't be possible. If the player had gradients of movement—if they could shift around in small increments or move diagonally—being surrounded or blocked wouldn't have the same binary effect. It's a mild reminder that freedom of movement isn't necessarily the universal fun-producer we may think it is.

This is a just long compliment, I guess. I think it's a wonderful system, and it's an instance of an old design that arose from technical limitations still having a place and purpose in modern gaming. I like it when that happens. It's a sensibility you can notice in games like Unity of Command , which sticks its complexity beneath the skin of the game. Understanding how a supply chain works will help you win, but operating the game itself is a cinch: click on a dude, click where you want to go, click on who you want to kill.

You also see the payoff of simple movement in Dawn of War II's spin-off mode, The Last Stand. It went from being a single-map co-op survival mode to a $10 stand-alone release with seven pieces of paid DLC . That's unprecedented. Plenty of games have survival modes: Mass Effect 3, Left 4 Dead, Age of Empires Online, Call of Duty—what did The Last Stand do? Instead of shepherding an army, you controlled a single hero character. That eliminated the selection click entirely, which probably halved the amount of input needed to play the game. It's not unlike the control schemes of MOBAs like League of Legends, most of which cut out the selection click middleman.

PC gamers have more buttons and modes of input at our disposal than anyone else. I can jump into Arma 2 with an infrared head-tracker mounted to my face , steering wheel in my lap, and desk-mounted joystick. But I love PC designers that exercise the restraint to make "less is more" their method.

Evan's a hardcore FPS enthusiast who joined PC Gamer in 2008. After an era spent publishing reviews, news, and cover features, he now oversees editorial operations for PC Gamer worldwide, including setting policy, training, and editing stories written by the wider team. His most-played FPSes are CS:GO, Team Fortress 2, Team Fortress Classic, Rainbow Six Siege, and Arma 2. His first multiplayer FPS was Quake 2, played on serial LAN in his uncle's basement, the ideal conditions for instilling a lifelong fondness for fragging. Evan also leads production of the PC Gaming Show, the annual E3 showcase event dedicated to PC gaming.