How players brought the freeform world of Genesis LPMud back from the brink

The 20,700 room universe is still going strong.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

This article was originally published in PC Gamer issue 323. For more quality articles about all things PC gaming, you can subscribe now in the UK and the US.

Genesis LPMud is one of the oldest online multiplayer games in the world: it’s been running for nearly 30 years. But six years ago it almost came to an end. This is the story of how an enthusiastic cadre of fans rallied to save it from extinction.

MUD (Multi-User Dungeon) was created by Roy Trubshaw and Richard Bartle at the University of Essex. It was a text-based fantasy adventure that multiple users could play over the university’s network. The first version was made in 1978, but in 1980 the university connected to ARPANET, the precursor to the internet, and MUD became the first online multiplayer RPG.

The original MUD, also known as MUD1, closed down in 1987, but it spawned a whole host of imitators, including Genesis LPMud. Genesis was made by the Computer Society at Chalmers University in Gothenburg, Sweden, and the ‘LP’ stands for Lars Pensjö, who created the game’s programming language—and who still materialises to rescue players from death whenever they get killed in the game. Genesis launched in 1989, and it’s been going ever since. US-based Cooper Sherry, aka Gorboth, is the current ‘Keeper’ of Genesis, the leader of the volunteer band of developers, or ‘Wizards’, who keep the game running. “We’ve never had a paid staff,” he says. “Nobody ever pays anything to play the game, so it’s all just hobbyists, creating the content as they have time.” He notes that little of the 1989 version of the game remains, “other than the oldest bones on which we still build the code structure”, but there is still content in the modern game that dates all the way back to 1992.

Magnus Holmgren, a Wizard who also roleplays as the thief Kiara, recalls he began playing Genesis in 1997 in the computer labs at his school in Sweden. “The internet was new at the time, so it was very cool,” he says. Along with around ten of his friends, he became totally hooked. “Most people didn’t finish school because of the game! They had to take an extra year, because they skipped too many classes.” Eventually, a ‘restrict’ option was added to the game to enable addicted players to actually ban themselves from Genesis for a set period of time.

<explain game>

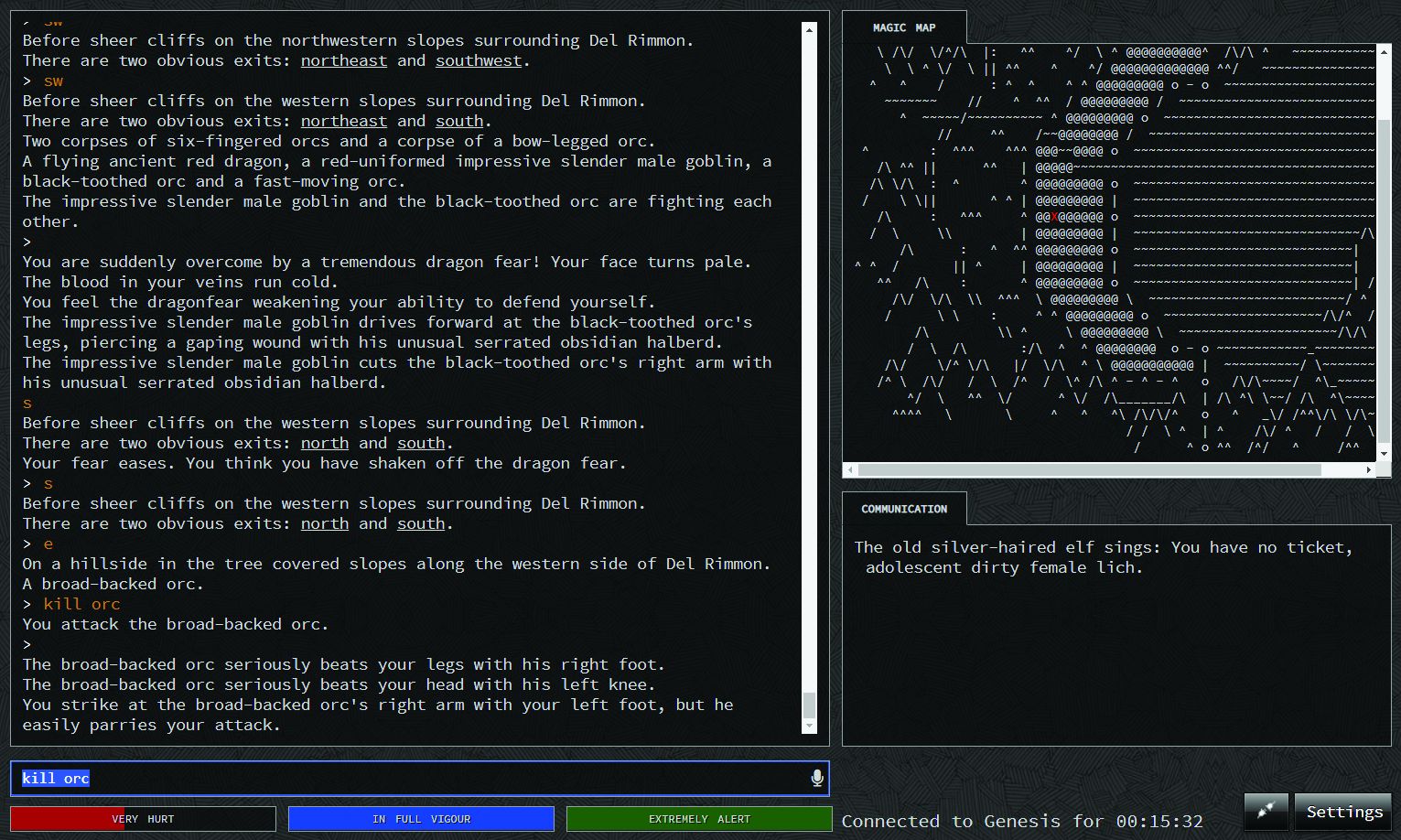

The game itself is a classic text RPG in which you travel by keying in compass directions and defeat baddies by typing ‘kill’ to attack them. But this simple interface belies bewildering complexity, a legacy of nearly three decades of gradual iteration. Magnus tells me that there are tens of thousands of different items to be found, all coded in by successive developers down the years. And those developers have gradually expanded the world to enormous proportions. “It’s been created over so many years that nobody knows how big Genesis really is,” Magnus informs me. He recounts a recent event in which players attempted to count all of the rooms in the entire game: they ended up finding more than 20,700.

But the key appeal of Genesis is its strong emphasis on complete player freedom. “The only thing I’ve ever heard that competes in a large scale with what we do, or any MUD can do, is EVE Online,” explains Cooper. “Just because EVE gives you these limitless options where you really can just create your own potentials, do ridiculous things, create, or ruin months or years of someone else’s work in one fell swoop. Our game allows that.” There’s no solid level cap in Genesis as such, he notes, “so people who have played for 25 years really have developed that much experience”. But once players reach the top rank of ‘Myth’, a punishing algorithm means that it becomes progressively harder and harder to attain more power.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The most powerful players rise to become heads of one of the nearly 70 guilds in Genesis, which include such esoteric outfits as The Secret Society of Uncle Trapspringer, The Rockfriends and The Bloodsea Minotaurs. There’s even an Actor’s Club. Some guilds will let anyone join, but the more hardcore roleplaying guilds will demand that prospective new members complete a series of tasks to prove their worth, says Cooper. “And who knows what the tasks are going to be? It’s nothing the game decides, it’s what the players decide.”

And that roleplaying is what really elevates Genesis in the eyes of its players. Because the game is so freeform, events can escalate at a player’s whim. In the past, the game world has been riven by an epic war between vampires and mystics, which snowballed to the point where every player ended up having to choose a side. But Magnus’s fondest roleplaying memory is a bit more intimate. “I remember one Christmas Eve when I got a bit too curious and got strapped to a chair in one of the biggest evil guilds,” he recalls.

The guild in question was the Morgul Mages, headed by a band of Nazgûl in the Tolkien domain. Peter Spellman, aka Celephias of the Morgul Mages, has been playing since 1992—and he was the one doing the tying up. “Kiara was being a proper pain in the behind,” he remembers. “She’s a clever thief type and was stealing anything that wasn’t nailed down. There was a price on her head and rather than simply try and find her and kill her, I entreated her to come to the tower to resolve the issue.” Unbeknown to Kiara, the room Celephias brought her to contained a special ‘shackle’ command that straps the player to a chair—once he typed the command, it completely disabled almost all of Kiara’s inputs. “I couldn’t move,” Magnus remembers, “I couldn’t even quit from the game—I couldn’t use any commands except talking. I didn’t know then it even had that feature!”

The only option for Kiara was to talk her way out of the situation. “I had to bargain to get free,” recalls Magnus. “A lot of other people got involved, and we were roleplaying for hours. That was a lot of fun!” Eventually, late on Christmas Eve, Kiara managed to trick her way out of the prison, but Celephias still has fond memories of their encounter: “Of course I was duped, but I think everyone involved had fun.”

End of days

But all this fun almost came to an end earlier this decade. After its glory days in the ’90s, Genesis began haemorrhaging players as graphical MMORPGs arrived on the scene. “The first game that was bad for us was EverQuest,” remembers Magnus. “And it was very similar to Genesis, too. People left for that. And then of course World of Warcraft, people left for that.”

This was the beginning of Genesis’s dark age. Cooper recalls this nadir: “The toughest period in the game was probably from around 2005 up until 2013. World of Warcraft came out around 2004, and created this new opportunity for people who wanted to live alternate lives online, which is what people had been doing with Genesis since the early ’90s. We saw a steep decline, and 2012 was our lowest point ever. That was when we really had existential thoughts, like, ‘Are we going to be able to continue?’ The lowest point was when I logged on and I did the so-called ‘who list’, which just tells you who else is on, and it said ‘you are alone in the realms’. I was the only player logged on. That only happened one time, but it was kind of an incredible moment for me, and I thought, ‘Wow, this could be the end.’”

Magnus had similar thoughts: “Everyone was saying, ‘Is this a sinking ship?’ and, ‘It’s dying and we’re going to have to close it soon,’ and stuff like that. That was sad.”

Cooper and the other Wizards spent most of the ’00s trying to modernise Genesis and make it a bit friendlier for the new players they so desperately needed. Cooper recalls that when it first began, Genesis was a somewhat forbidding place: “The game in the early years had a very big reputation of really unfriendly administrators who would just delete you on a whim.” Players who hadn’t logged on for over 100 days would have their characters summarily deleted. And Magnus remembers that being killed in the game came with an unbelievably harsh penalty for players: “You lose a lot of experience when you die. And when I started playing, it was 25% of all your experience, which is a lot.”

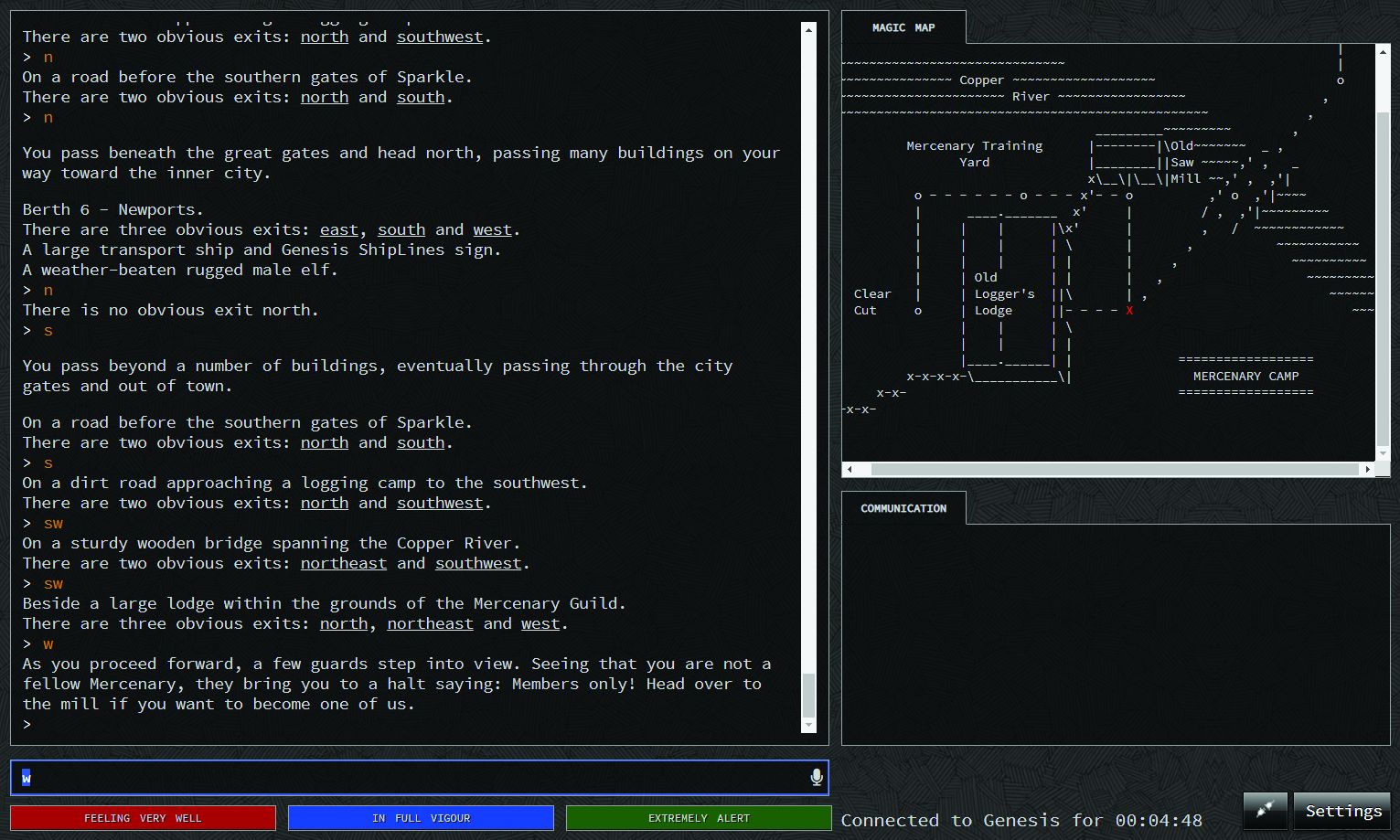

As well as dialling down the death penalty and generally being less draconian, the Wizards worked on making the game a bit less intimidating. For a start, it was almost impossible for new players to learn how to play Genesis, an old hangover from its birth in cliquey computer clubs, says Magnus: “In the old days people relied on being in computer labs with other people and learning from them.” To help new players learn all of the many text commands and intricate systems, Cooper coded a lengthy tutorial – so now when you begin a game, the first few hours are spent learning the ropes on Tutori Isle.

And in the early days, players were expected to draw their own maps on paper to keep track of where they were. To make things easier, the Wizards decided to add an ASCII map to the game. But as Magnus notes, “It takes a lot of time to change stuff around here, because you’re relying on people doing stuff in their spare time.” This, combined with the dizzying number of rooms in the game, meant it took an astonishing ten years to complete Genesis’s map.

Another big change was the creation of a fancy new website in 2010 with detailed explanations of the game world and a forum for players. Genesis members even raised funds to pay Denis Loubet, the artist for the ’80s Ultima games, to illustrate it. Yet even after all of these painstaking improvements during the ’00s and early ’10s, Genesis was still losing players at an alarming rate.

The comeback

The big turnaround finally happened in 2013. The Wizards created a new client that would allow the game to run on any browser instead of requiring players to download third-party software. But most importantly, the Wizard Cotillion (Erik Gävert) decided to add the game to the Google Chrome Store. “That was probably what saved us in the end,” says Magnus, “because then we were exposed to a lot of new players and got ranked really high, really quickly. We did some campaigns to get our existing players to give us good reviews, and when new players came in, a lot of old players heard about it and returned, too. And it’s been going in the right direction since then.”

Now, Cooper reckons they have around 2,000-3,000 active users who show up at least once a month, and around 200-300 who log in daily. And whereas once the average number of daily users dipped into the single figures, now it’s common to find 50, 60 or even 100 users online at once. “It’s funny because, you know, World of Warcraft would find [those numbers] to be the end of the world,” smiles Cooper. “But honestly our game could probably only reasonably handle, at the very extreme ends of things, maybe 200-300 players online at once, which would double anything we’ve ever seen.” Indeed, the sudden influx of new players after the Chrome Store launch caused parts of the rickety old game to break, necessitating speedy fixes.

One of those new players is Mateusz Nowak, who began playing MUDs in Poland 20 years ago and now lives in the United Kingdom. Over the years he gradually drifted away from text-based games in favour of MMORPGs and various console games. But he discovered Genesis just three weeks ago and is already hooked. When I asked him about the appeal of text-based games like this one in an age of dazzling MMORPGs and blockbuster releases, he replied: “What I like the most is the feeling of not being bound to certain paths or options, and—of course—the need to use your own imagination to visualise things, players and locations in your head. When you and your friend read the same description, you probably visualise the same thing in completely different ways, which is brilliant. You are not simply given everything, you have to use your imagination all the time.”

For Cooper, however, the main appeal is the people: “The thing that I find most compelling about Genesis is the social interaction. I think the fact that it’s so entirely governed by players rather than just game mechanics is what’s magical. It’s just wide open, the scope of what you can do in the game, and the type of person you want to be in the game.”

Couples have met through Genesis and got married, and the children of some of the oldest players have even started playing the game themselves. Now, thanks to a group of dedicated volunteers, their grandchildren might get a chance to play it, too. If you want to join them, head over to the Genesis MUD site.