Here are all the times companies have tried to make 'Netflix for gaming'

From GameFly to OnLive, a lot of game streaming services have come and gone before Google's latest announcement.

Google announced Project Stream earlier this month, a "technical test" for a new service that will let players stream games. The idea is simple: instead of owning games or machines that run them, we'll pay a subscription service that does the heavy pixel-crunching remotely and streams great-looking graphics to us with minimal latency. The idea is often called "Netflix for gaming," and would theoretically allow us to play the latest games at the highest graphical settings without having to own a high-end PC.

Within a week of Google's announcement, Microsoft announced its own take on the same idea: Project xCloud. While Google is experimenting with Assassin's Creed Odyssey right now, Microsoft's first public trials won't start until next year. Graphics card manufacturer Nvidia also launched its own service called GeForce NOW earlier this month.

So many big names going all-in on this idea might mean the time has finally come. But for all the pie-in-the-sky sales pitch lingo, game streaming still has serious technical hurdles to overcome. These challenges are no joke. Connectivity, lag, and licensing issues are significant enough problems that they've sunk or delayed the idea every other time it's ever been tried. Here, in brief, is a history of the pursuit of 'Netflix for gaming.'

G-cluster (2000 - 2016)

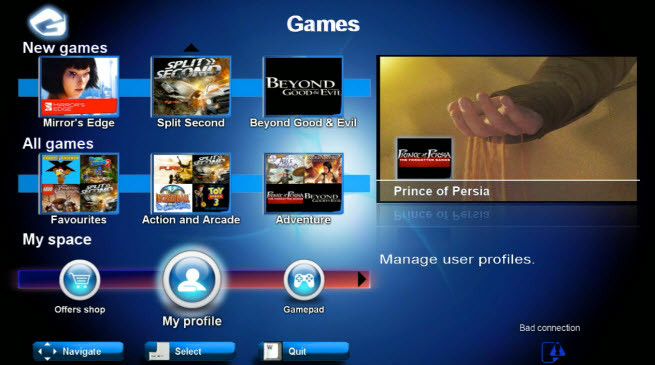

By far the earliest attempt at cloud-based game streaming was G-cluster, which started in 2000. Its focus at the time was entirely on console games and family-friendly puzzle games. Essentially, G-cluster wasn't pitching the idea to gamers, it was pitching it to cable networks. If a cable provider or ISP already has a set-top box installed in everyone's living room, they realized, then adding a plug-in device that streams games should be an easy sell.

And it worked, at least for a while. G-cluster got its biggest break in 2010 when French telecom giant SFR used its tech to launch game streaming services to eight million customers. Even though this was a big breakthrough for them, that success never gained momentum. G-cluster filed for bankruptcy in 2016.

Untitled Crytek Streaming Service (2005 - 2007)

Crytek is best known as the developer of Crysis, the game hardware-obsessed PC gamers spent a decade using as the ultimate benchmark. If there was anyone who could make really high-end graphics playable over a streaming connection, it would have been the folks at Crysis. Though Crytek spent two years researching it, it stopped the untitled project because of "doubts about economics of scale," according to Crytek CEO Cevat Yerli. Bandwidth was just too expensive to make it viable, he said.

Yerli's response sets up a pattern that was be repeated again and again—most of the technology to make a "Netflix for games" work exists, but we're all waiting on bandwidth and internet speeds to get faster and cheaper.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

OnLive (2010 - 2015)

When it launched in 2010, OnLive was labeled as a "console killer" by prognosticators who could clearly see the potential of game-streaming services. "OnLive breaks the console cycle," OnLive founder Steve Perlman was quoted as saying to the BBC. "We don't need new hardware devices."

OnLive is also the closest we got on this list to those pie-in-the-sky ideas we started with. Any device could stream and play a game, even your crappy laptop that wasn't powerful enough to play high-end games with advanced graphics tech. The trouble was the lag. Usually the video streamed well enough, but lag between control inputs and on-screen action varied widely from game to game.

As a result, OnLive didn't kill consoles or PCs so much as just add an unnecessary fee to them. It was convenient to play free game demos without downloading them, but was it worth $5 a month just for demos? "Renting" a game with OnLive was effectively the same as buying it, and prices over and beyond the monthly service fee ran accordingly: $40 to rent Assassin's Creed II, $50 to rent Just Cause 2, $60 to rent Splinter Cell: Conviction. It's not much of a sales pitch. 'OnLive: It's $5 more expensive than just buying the game, plus it doesn't work very well.'

In 2015, Sony purchased all of the most important parts of OnLive's technology, and OnLive shut down.

GameFly Digital / GameFly Streaming (2011 - 2018)

When it comes to aiming for "Netflix for gaming," GameFly took it literally. Back before Netflix was an online streaming powerhouse, it was a quaint company that ran a DVD-by-mail rental exchange service. GameFly ran the same way, literally mailing game discs and console cartridges for handheld games like the PlayStation Vita and Nintendo 3DS.

Like Netflix, GameFly started expanding into game streaming after purchasing Direct2Drive, an early Steam competitor, in 2011. Going by GameFly Digital, the service struggled with all the same problems experienced by its competitors: restricted bandwidth and laggy streams. GameFly sold GameFly Digital in 2014, and the online streaming tech was relaunched by its new owners as, weirdly, Direct2Drive. GameFly continued to offer game streaming services under the name GameFly Streaming until Electronic Arts bought everything associated with game streaming technology earlier this year.

As of now, GameFly is still trucking along with its original business: mailing physical game discs to customers as rentals.

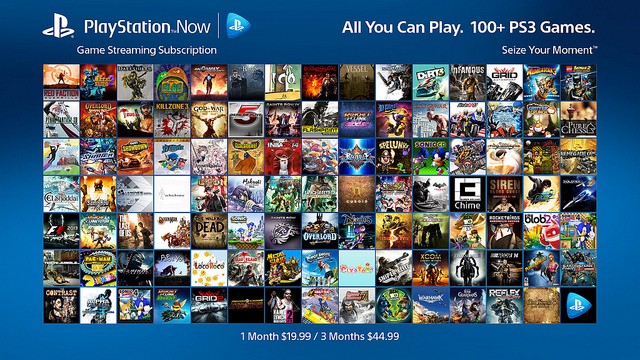

PS Now (2014 - )

Sony launched its own private streaming service in 2014, and it might have been an early indicator of how the next few years are going to go: a subscription service for every company, a dozen separate subscription charges to pay for every month for gamers. PS Now was at least a great addition to us here in PC gamer land. Because it launched on PCs as well as on PlayStation consoles, for the first time PC gamers had access to PlayStation exclusives.

For the most part, that probably wasn't a big deal: if you really, really wanted to play the new God of War, you could just buy a PlayStation, after all. But for a lot of PC gamers, PS Now gave us a cheap way to explore decades of PlayStation-exclusive classics like Journey, The Last of Us, and Shadow of the Colossus. Naturally, we had to write up a list of our favorites.

PS Now also got closer than ever to the quality level that makes a streaming service viable. The games available play well and lag is minimal, at least depending on how far away from a data center you are and what your internet connection is like.

The future

It's understandable that many PC gamers are skeptical or outright hostile to the idea of game streaming. We love tinkering with our hardware, building and overclocking PCs to get the best performance we can. It's part of the hobby. And though properly owning a new game is far rarer than it used to be—we have to look to specialty distributors like GOG to find DRM-free games—streaming even further distances us from ownership, to the point that we won't even host the game files locally. What of modding, then? Or simply tinkering with a config file?

Game streaming feels like the final step toward turning our PCs into mere screens that we use to access subscription services. While some companies will surely hold onto the old ways, be prepared to face change, or at least an attempt at it. With all the money being invested in streaming by Sony, Microsoft, Nvidia, Google, and others, you can pretty safely bet that within the next five years, 'streaming exclusive' will enter our vernacular.