If you want more Fallout in these trying times, have you considered playing Wasteland 3?

It's a short hop from one irradiated hellscape RPG to the other.

The next Fallout is so far away it's not even worth speculating about when it'll happen. Fortunately, just like in Star Wars, there is another. You can always play a Wasteland instead. The game that directly influenced the original Fallout eventually gave rise to a series that collected the debt by continuing the style of the original, isometric Fallouts, culminating in an under-rated CRPG more people should play.

First, let's rewind a little. The history of every roleplaying game goes back to Dungeons & Dragons eventually, but Wasteland arrives there via a particularly direct route. When D&D came out in 1974, its rules were more toolkit than game—a messy bundle of ideas that had to be house-ruled into shape. Ken St. Andre decided to put together a simpler alternative, designing Tunnels & Trolls to play with his friends, and publishing it in 1975 so other people could play it with their friends. It was the second tabletop RPG to be professionally published.

Michael Stackpole, who would go on to write a towering stack of BattleTech and Star Wars books, worked on Tunnels & Trolls as well. He also took its basic rules, bolted on a skills system, and turned it into a modern-day tabletop RPG called Mercenaries, Spies and Private Eyes that came to the attention of Brian Fargo, the founder of Interplay.

At this point Interplay had just released the first two games in The Bard's Tale series with Electronic Arts. Traditional fantasy RPGs, they'd been successful enough that while EA wanted another RPG, the studio had relatively free reign to make it about whatever they wanted. Fargo, a Mad Max lover, wanted to go post-apocalyptic.

He brought on board a trio of Tunnels & Trolls designers: St. Andre and Stackpole, as well as Liz Danforth, who would go on to become quite well-known as an artist, illustrating Magic: The Gathering cards among many other things. They brought the ruleset from Mercenaries, Spies and Private Eyes with them, including its skills. The implementation in Wasteland feels clunky today—when a boy tells you there's a cave hidden by some bushes you have to walk up to every bush in the area selecting the Perception skill and then a bush until you find the right one—but still, building characters by selecting skills rather than race and class was something few other CRPGs of the 1980s offered.

Wasteland cast you as Desert Rangers in post-nuclear Arizona, a squad of troubleshooting wanderers who traveled from town to town dealing with problems. It wasn't a particularly gritty vision of the post-apocalypse, peopled with mutant molerats and cyborgs as it was, but that random mashing together of sci-fi influences made for a nice contrast with the dry military sf of the Desert Rangers themselves.

Something else brought over from Tunnels & Trolls, which catered for solo play with scenarios in a "choose your own adventure" style, were numbered paragraphs of additional story text in the manual. Shifting a significant amount of the game's text onto paper had the advantage of reducing the disk requirements, which was a big deal, because Wasteland needed plenty of space for its persistent, open world. Where many other RPGs of the time consisted of dungeons and wilderness locations that reset each time you returned to them, your actions left marks on Wasteland's post-nuclear Arizona. Not all of your actions, but enough to be notable. The defining memory of Wasteland for a lot of players is killing a rabid dog, then being attacked by the kid who owned that dog, shooting him too, and then having events escalate until they go to war with an entire settlement.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

There was only one save game, so you'd have to live with any outcome you survived. Given that many players didn't have hard drives when Wasteland was released in 1988, if you didn't make a copy of the floppies beforehand you'd never be able to replay the pristine version—your save would straight-up overwrite the world data.

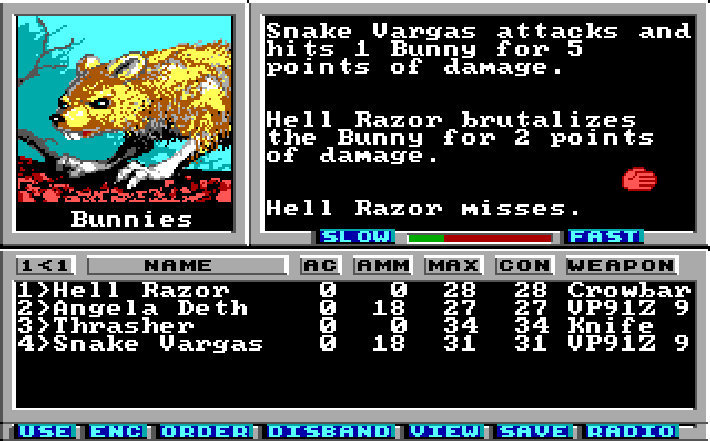

Wasteland was rereleased in 1993 as part of Interplay's 10th anniversary anthology collection, and honestly even back then it was too harsh for me. While it shared a deep silliness with the light-hearted Tunnels & Trolls, it was also intensely punishing in the style of the time, and you were likely to be killed by bunnies before uncovering much of the story. There was a slightly improved version released in 2020 called Wasteland Remastered, but it's the kind of clunker I wish had a full remake rather than a spit-polish remaster.

Wasteland 2: Nuclear-powered Boogaloo

Electronic Arts planned to make its own sequel to Wasteland in-house, without Interplay, though when it was finally released under the name Fountain of Dreams it was no longer billed as a Wasteland game. Which is probably for the best, given that our own Richard Cobbett compared it to "a piece of homework started at 5AM on the day it's due to be handed in, after three weeks of doing anything else."

It's well-known that while EA was sitting on the rights to Wasteland, Interplay made Fallout as a spiritual successor instead. But the desire to make a direct sequel remained, and when Fargo obtained the rights in 2003, he finally had the chance—though it wasn't until the Kickstarter boom of the early 2010s set off by Double Fine Adventure that he found a way to make it work.

When his studio InXile pitched Wasteland 2 on Kickstarter, it raised $2,933,252—more than three times its $900,000 goal. St. Andre, Danforth, and Stackpole returned to work on it, and all that excess Kickstarter money paid for additional hires including members of Obsidian and composer Mark Morgan, who had worked on the Fallout games.

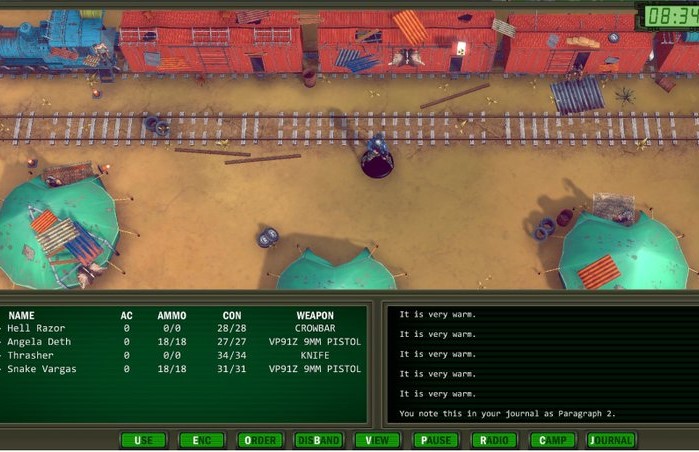

Where the original Wasteland had the menu combat of The Bard's tale and an overworld view reminiscent of the Ultima games, Wasteland 2 looked and played a little more like the first two Fallouts, complete with isometric view and tactical combat. It kept plenty of nods to its predecessor though, like the fiddly skill system complete with seemingly useless but actually vital abilities like Toaster Repair. It also nodded at the original's cast, having one of the first game's pre-generated party members called "Angela Deth" return as an NPC to act as your Wasteland guide.

It also got a bit bloated, attempting to justify that excess budget with excess scope, and a second half set in Los Angeles that's not as good as its first half, set in the Arizona desert. Still a good game, but held back from being a great one.

Third time's the charm

Even though Wasteland 3 was another crowdfunding hit—on Fig this time rather than Kickstarter—the scope was kept in check. It's a meaty RPG but one that isn't 100 hours long, which is why it's the Wasteland game to play if you've yet to give the series a chance.

Though you play a squad of Desert Rangers again, this time the setting's much less arid. Snowy Colorado provides a backdrop for a fish-out-of-water story about outsiders come to clean up local problems and oust corrupt authorities. In some ways it feels more Fallout than ever, giving you a vehicle to cross the overworld map in like the Fallout 3 we might have got if Interplay had kept making them. But it also does things Fallout can't, thanks to having a pre-apocalypse timeline much closer to our own. That's most obvious in the questline involving an AI based on Ronald Reagan that's now worshipped as the God-President.

Wasteland 3 is the Wasteland game to play today because it's the culmination of everything good about the Wasteland series, and about the isometric Fallouts. It's got dynamic combat—unlike Wasteland 2 it has both stealth and called shots, with characters earning "precision strikes" they can unleash to, for instance, target a robot's AI core and turn it against its allies. It's got wackiness on the side, like the aforementioned digital Reagan, as well as a love of killer clowns and a set of animal sidekicks to collect, but it's also got a serious central questline about figuring out which of the competing factions to back. And if you put in all the effort to get the car working in Fallout 2 then were annoyed none of the sequels let you do something similar, well, Wasteland 3 gives you a truck you can upgrade until it's basically a goddamn tank.

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.