Constance is a metroidvania that wants its monsters to mean something

I want them to mean something, too.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

Constance's store page on Steam insists its titular heroine, the one with a flappy cloak, slender weapon, and impeccable animation, is more than just another Hornet. This is a game set in "a colorful but decaying inner-world, created by her declining mental health" where I can "Experience playable flashbacks about personal struggle, creativity, work-life-balance, and inner purpose."

I'm not convinced something with boss health bars that lets me pogo-jump over spikes is the best way to explore such topics, but I am intrigued. A Short Hike managed to combine a cute adventure with personal growth and deep, touching concerns for others. Vampire Therapist does a masterful job mixing very serious and very human issues into a ridiculous and often genuinely funny tale. Celeste's tough climb is expertly interwoven with a moving story of depression and anxiety, and all the struggles that go with it.

Which is why several hours later I'm helping a silent Constance paint a picture during one of the game's surprisingly rare flashbacks. No matter what colors I pick or where I place them, every sketch and stroke seems to be wrong. A neglected plant sits in the background. Once this interactive depression session's over I get back to leaping about a colorful world, and this frictionless and uncommented memory is never, ever, brought up again.

Hoping all of this professed meaning has perhaps been packed into the game's monsters instead, I start playing close attention to everything I see. I have been promised "enemies and characters representing different aspects of her psyche and personal history", after all. That's basically Silent Hill territory, and I am all for poring over tiny little freaks packed with symbolism.

I get a walking bunch of keys with goop on them instead. They wander back and forth and do absolutely nothing else—such as run off and hide the way I'm sure my real-life keys do whenever I go looking for them—when I try to approach.

The enemies that follow are if anything even worse. What meaning am I supposed to glean from a boxing robot with a moustache and a propeller on its head? A flame-shooting armillary sphere? I hit them all with a giant brush and they disappear in the same flash of light and a splattering of grey paint. I don't color them in or clean them up. Constance has no thoughts, good or bad, on these violent experiences. They're just something to whack until they drop a little currency.

Constance not having any thoughts is a recurring issue with her adventure, the one that has gone out of its way to insist there is method and meaning behind everything I see. Does the dreamlike astronomy area exist because she finds comfort in stargazing? Or is everything in the place attacking her because the adults in her life wanted her to take a science-oriented path and she pursued a career in art instead?

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

No amount of careful analysis of her surroundings or her diary, which somehow manages to convey less personal insight and warmth than my weekly shopping list, unravels these superficial mysteries. Even after reaching the end credits I'm left with the awful feeling it's styled this way simply because the NPC found in the area, Vincent, is a visual homage to Van Gogh's Starry Night. I don't know if she likes that, either.

Other characters suffer from a similarly hollow train of thought. Frida, with her floral motif and prominent eyebrows, is an obvious tribute to the artist Frida Kahlo. Another resembles one half of Klimt's The Kiss. These are wonderful things to be inspired by; I just wish their significance for Constance didn't end at Noticing Things: Gamers Who Went to Art College Edition (hi). Understanding the people and works represented adds no depth to any of the simplistic "find the object, help the person" problems in here, all of which are solved by jumping around and hitting in the face anything that gets in my way.

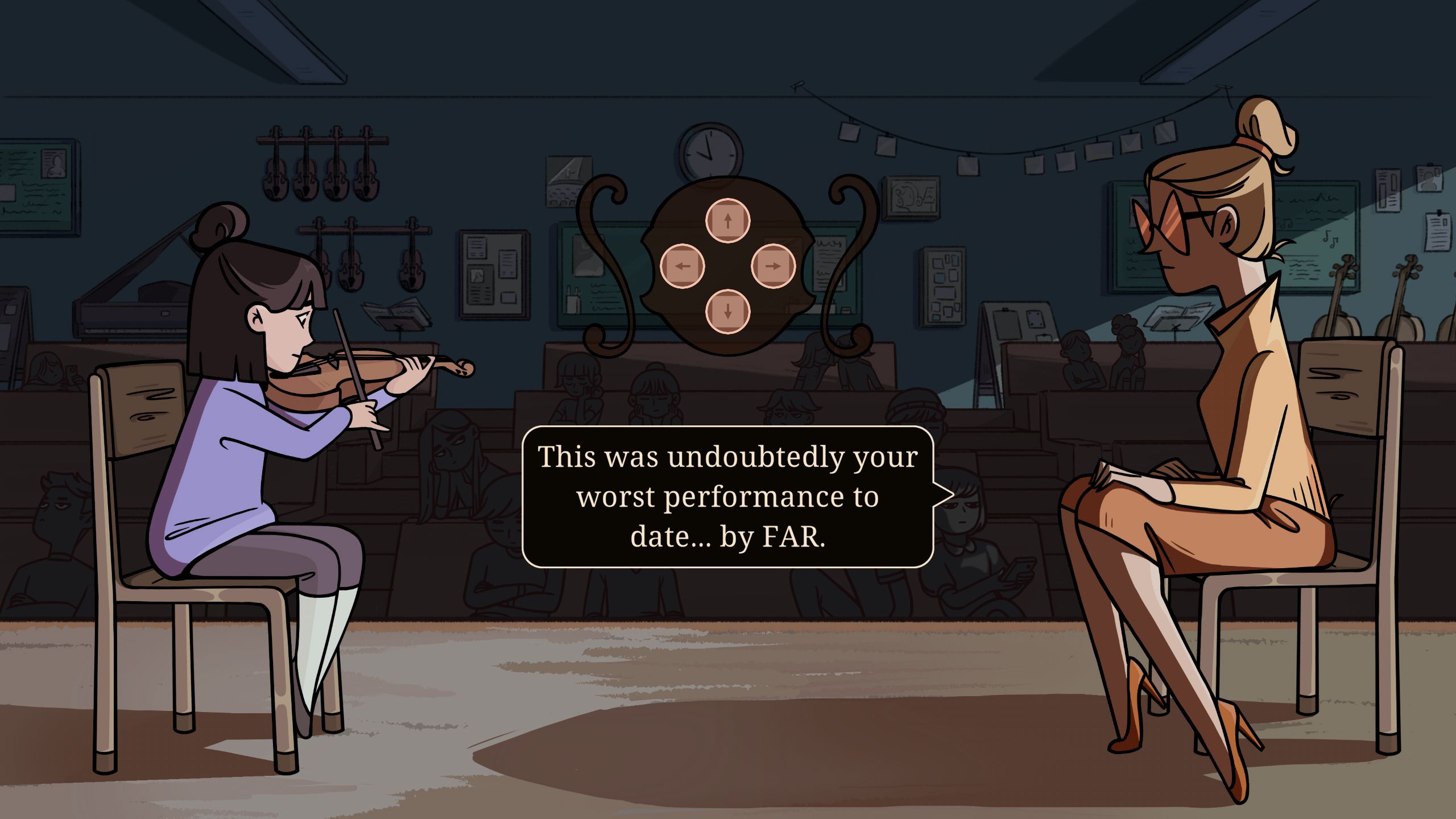

I think back to the warning screen, shown every time I start the game. "This game explores themes of mental health, including burnout, familial conflict, trauma, anxiety, and depression." I would like to have played that game. Playing through a nightmarish violin lesson opposite the world's most discouraging teacher is clearly upsetting and unpleasant, but it isn't an exploration of anxiety, especially not when the memory's brought up one time, discussed with absolutely nobody, and then swiftly pushed away forever.

I didn't need Constance to be profound. I didn't need to play a game that made me weep into my keyboard or launch a thousand thinkpieces. But I was hoping I'd get to play something that would at least follow through on its own ideas, and convincingly weave them into its genre of choice. The skills Constance gains along the way would have been the perfect place for this. These abilities allow her to literally reach new heights and easily achieve things that were impossible before. The metaphor pretty much writes itself.

It should, anyway. Instead Constance automatically paints new skills on blank canvases she just happens to find lying around, giving herself techniques she didn't need before this point, which nobody spoke to her about, and which don't mean anything outside of typical game-y traversal. Why does the sight of one compel her to paint a directional stabbing ability? What does that say about her and her personal struggles? I'm not told, and I'm not invited to dwell on the matter either.

I wouldn't have minded so much if the game hadn't been so keen on leading me down this narrative dead-end. The game itself, even when judged against all five million (-ish) metroidvanias with a twist already on Steam, is a good one. Movement's fun, fluid, and speedy. Every new area seems prettier than the last. Boss fights demand I attack and dodge with an engaging amount of precision. Speedrunning is encouraged (there's even a dedicated toggle in the settings), and I'd quite like to give it a go when I find some spare time.

I just wish the game had more to say—anything to say, really—about the one person it supposedly pins its entire existence on.

Kerry insists they have a "time agnostic" approach to gaming, which is their excuse for having a very modern laptop filled with very old games and a lot of articles about games on floppy discs here on PC Gamer. When they're not insisting the '90s was 10 years ago, they're probably playing some sort of modern dungeon crawler, Baldur's Gate 3 (again), or writing about something weird and wonderful on their awkwardly named site, Kimimi the Game-Eating She-Monster.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.