The race to save Japan's incredible '80s PC gaming history before it's gone

Square, Enix, and Game Arts: 3 origin stories from Japan's PC boom, from inside the Game Preservation Society's archive.

It's late afternoon in Tokyo, and in the narrow three story home that serves as the headquarters of the Game Preservation Society, I've just learned about Jesus. In the west, when we talk about videogame developer Enix, we're probably talking about Dragon Quest, which inspired Final Fantasy and many other JRPGs on Nintendos and PlayStations over the years. Joseph Redon would much rather talk about a PC game like Jesus, which was made by Enix around the same time as the first Dragon Quest way back in 1987.

Like most of the thousands of games in Redon's collection, I've never heard of Jesus until he shows it to me. The mission of the Game Preservation Society, the non-profit he co-founded several years ago, is to collect, archive, and protect Japan's PC games, most of them made in the '80s and '90s before consoles took over and doomed games like Jesus to obscurity. Any game I point to he can tell a story about, casually dishing out some of the history of who made it and why it's special.

He loves every second of it. When he begins to talk about Enix, he slips into the role of a storyteller born into an oral tradition, passing down a lifetime of knowledge accumulated in Japan that could only be accumulated in Japan. Because off the island, Japan's PC games are all but completely unknown. The Game Preservation Society exists to make sure they aren't forgotten.

Enix: The publishing pioneers

Many other PC developers abandoned ship for the more lucrative Famicom. But Enix was different.

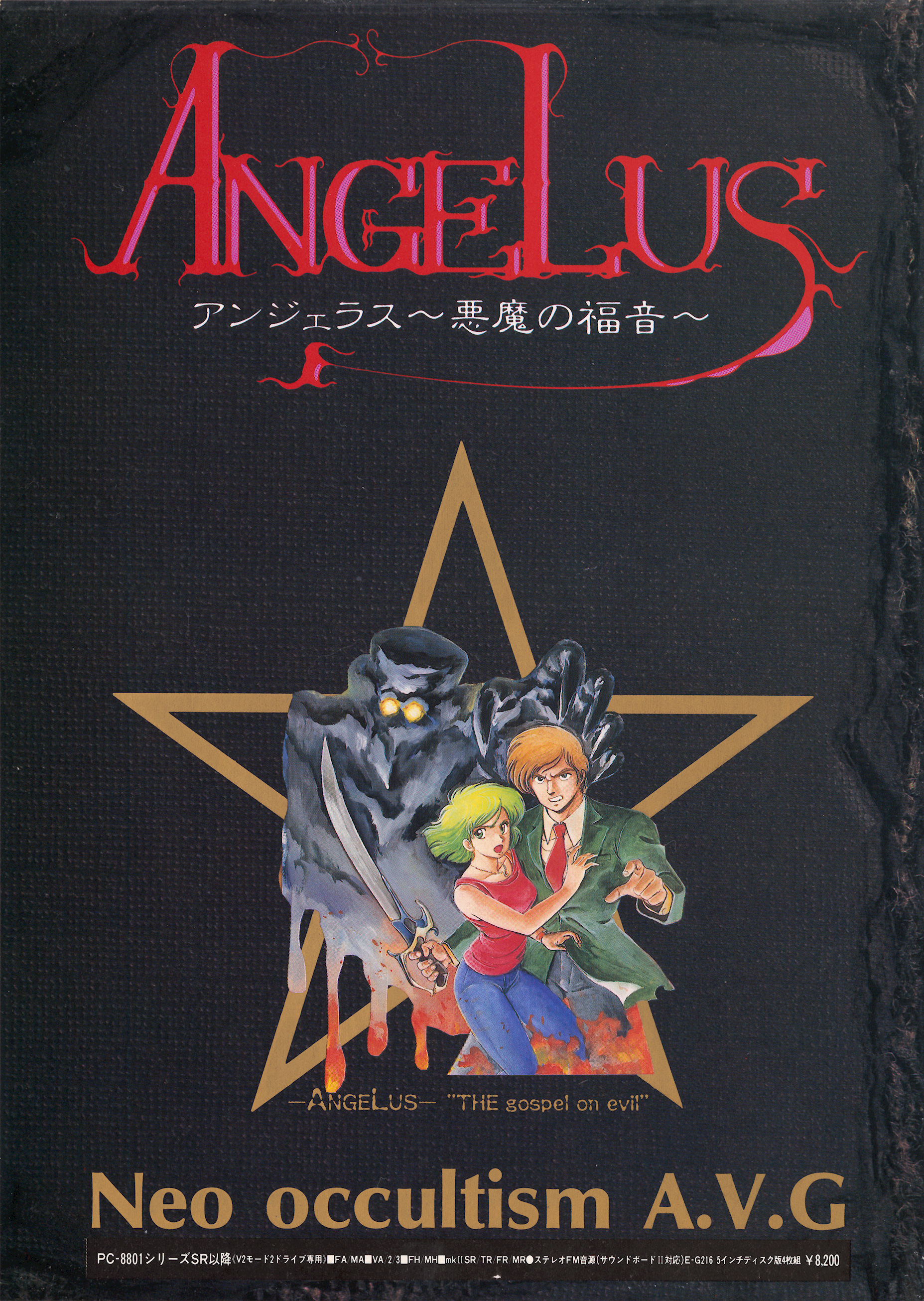

"Enix is a very great publisher, but this is not the history everyone knows," Redon tells me as we flip through the covers of '80s RPGs and adventure games. Cover after cover is imagination fuel that evokes a breathless "I need to play this." They look so polished it's surprising that back then, you didn't need to sell all that many disks for a game to be a big success.

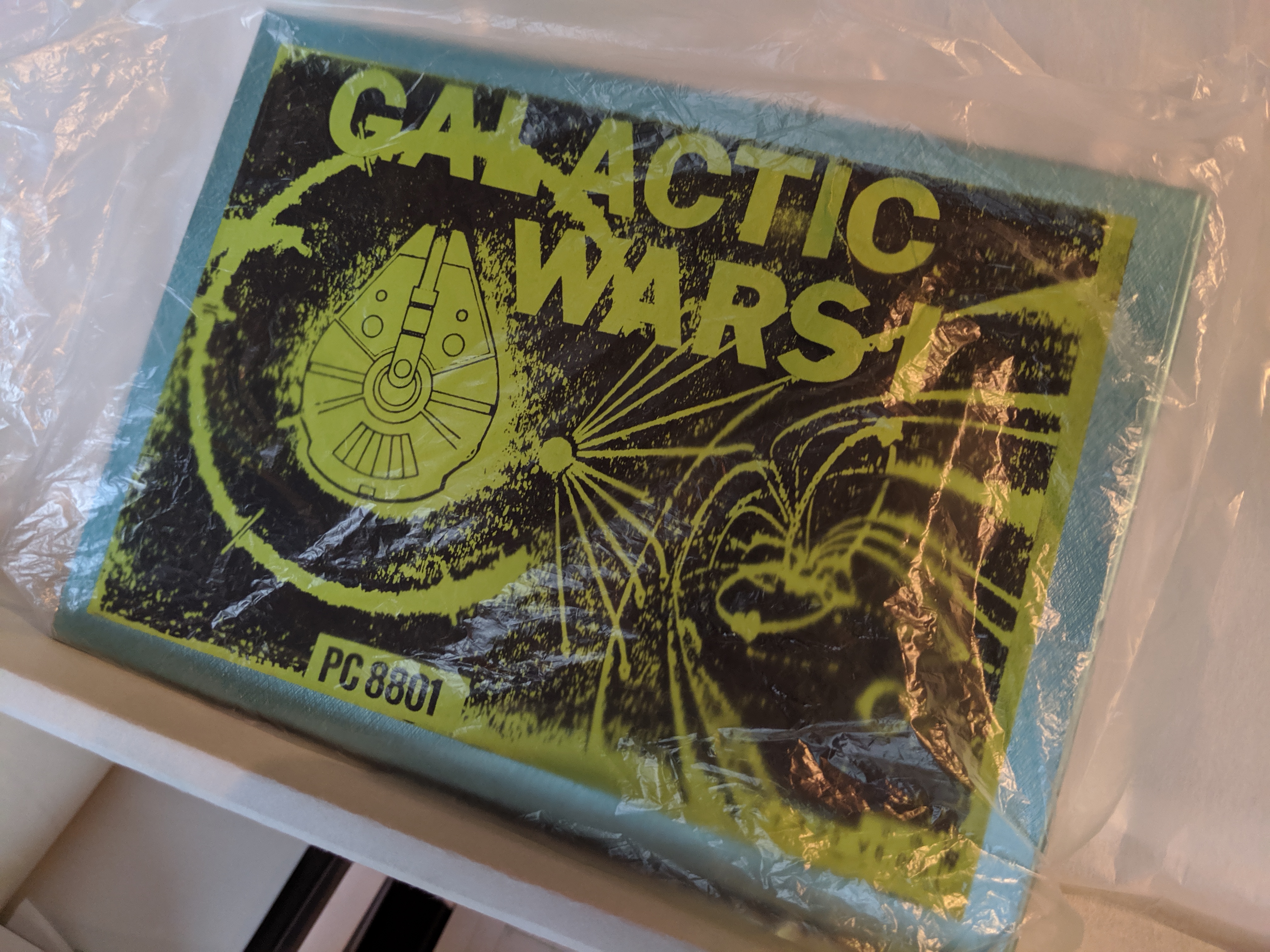

"When you sell 50,000 copies, you're rich," he says. That's how it was for PC developers in the mid-1980s—small teams or even individuals making games for an audience eager to use their shiny new computers, before Nintendo's Famicom took over. In 2019, the common wisdom is few Japanese gamers play on PCs. But you have to remember that in the '80s, Japan was riding high on an economic boom. Japanese technology was the hottest shit on Earth, and personal computers—specifically the NEC PC-8801 released in 1981—were selling gangbusters.

"Most houses were rich in the '80s in Japan, in the bubble," Redon says. "Buying new stuff every year. Let's buy a PC, a new car, a new TV." Enthusiast magazines popped up for PCs, promoting and reviewing software and games, which were typically made in months on tiny budgets. Enix started as a publisher, and decided to round up talent by offering a $5,000 prize to hobbyist programmers who submitted quality games. Out of hundreds of entries Enix picked the best to release on the PC-88 and competing PCs, quickly gaining a reputation for quality. Enix's collective of hobbyists included Yuji Horii and Koichi Nakamura, who teamed up to make a Famicom RPG: Dragon Quest. It's a smash hit, and Dragon Quest 2 is even bigger, selling millions, when most successful PC games sold only tens of thousands of copies.

And this is where Enix's PC history really gets interesting.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"Do you think they will invest time and money to make any more PC games that will sell only 10,000 copies?" Redon asks. "The games could even cost as much as a Dragon Quest [to make]. Even more, because it's PC. No limits in memory—just increase the number of floppy disks. You have to make a gorgeous package. A 100 page manual. Advertise in many magazines. Why would you do it?"

Many other PC developers abandoned ship for the more lucrative Famicom. But Enix was different. "It's a publishing company, but it's a collective of game creators. They don't dream about Famicom. They dream about making games. They dream about high quality graphics. About making digital music. About making always bigger games. Huge stories. They make entertainment, not money.

"So they tell Enix: 'We want to make games for the PC. This is the platform we think is the best for making the games we want to make.' And some developers, some publishing company investors, say no, it takes too much time. But Enix says: 'Okay, do it. Even if we don't make a lot of money, okay.' From the beginning we're here to follow the creators, help them to market their dreams.'"

Maybe that's a romanticized history. Then again, maybe not.

Enix did keep releasing PC games through 1993, including one Redon highlights, Misty Blue, in 1990, and the wonderfully named Jesus 2 in 1991. I've tried to imagine how my child self would've reacted to a Japanese game called Jesus 2 on a Wal-mart shelf, but the boldness and mystery of it probably would have shattered my mind.

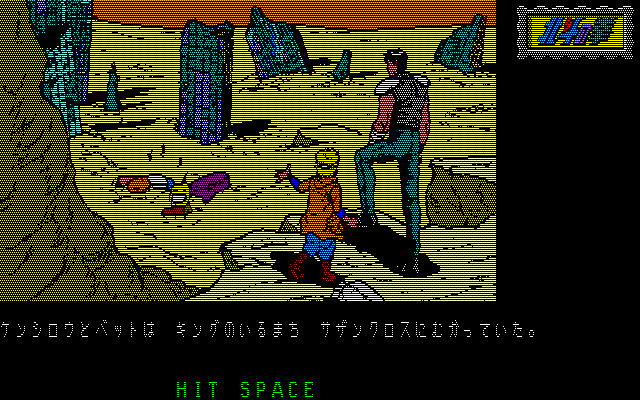

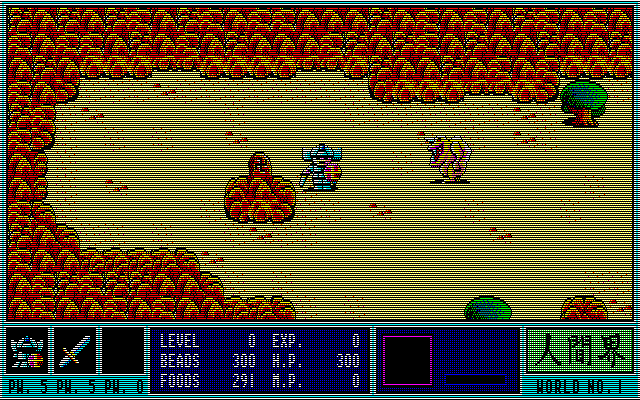

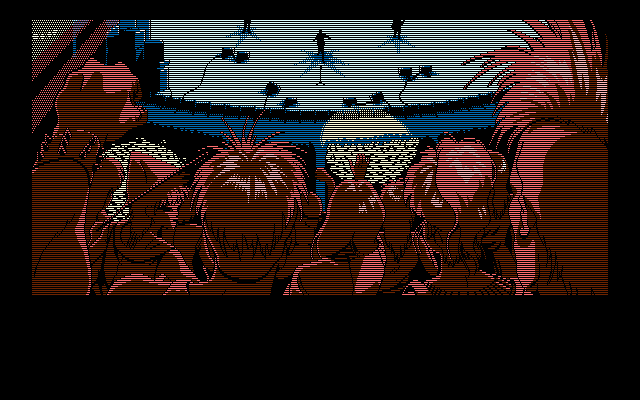

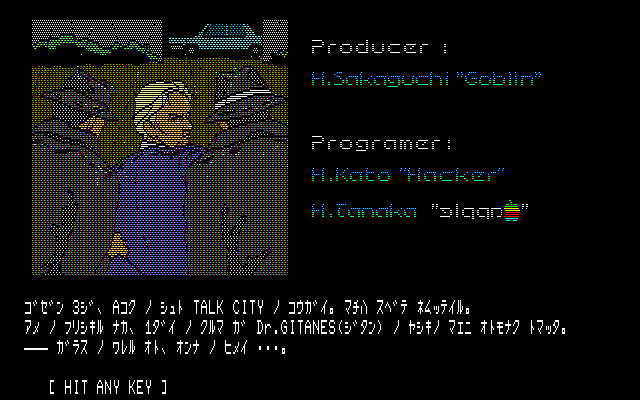

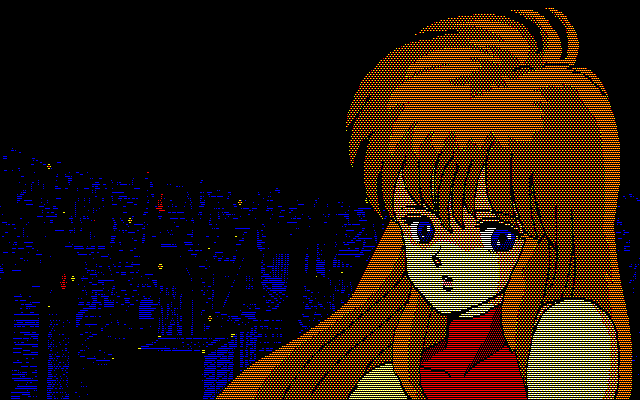

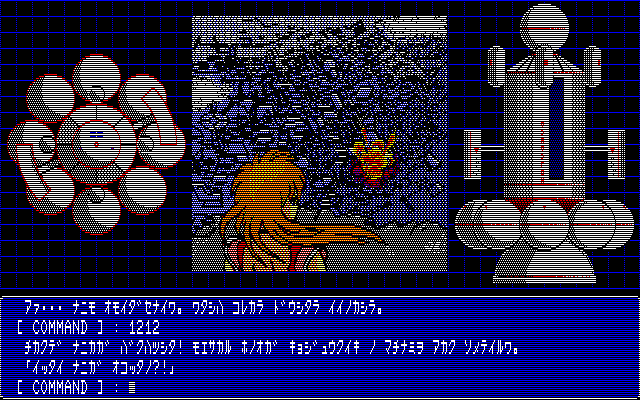

Jesus, you may be surprised to learn, is the name of an orbital space laboratory where this adventure game is set. It's more or less a playable manga about an Alien-esque monster loose in the station. Like many of the PC games of the era, Jesus is a text-heavy adventure, largely made up of static images and loads of dialogue.

"You have to understand that PC-88 is not made for gaming," Redon says. The computer didn't have hardware to support sprites or even scrolling, but developers worked within those limitations to make games that took advantage of the PC's strengths: High resolution monitors, storage space, and, starting with the 1985 model PC-88 MkII SR, a Yamaha sound chip that could do FM synthesis. It was the predecessor to the Sega Genesis/Mega Drive's famous chip, and gave musicians the power to write music that still sounds fantastic in 2019.

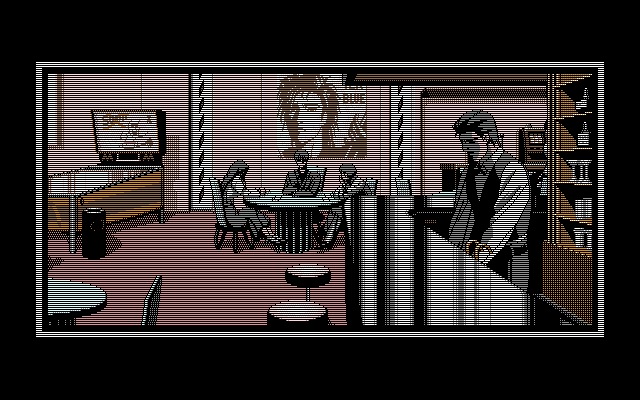

Misty Blue is the perfect example. It's a mystery starring a young musician trying to clear himself of a murder, with a banger of a concert intro. You spend most of your time in conversations with other characters, with a meter that fills or depletes based on your dialogue choices. "At that time, it was the most advanced graphical game you could find. Far away from what was possible on the Famicom or Sega Mark III," Redon says. Again it's essentially a digital comic, more stills than animations, but the pixel art is almost TV anime caliber. And that music. A year before Streets of Rage, Yuzo Koshiro was channeling '80s eurobeat pop into lively chiptune.

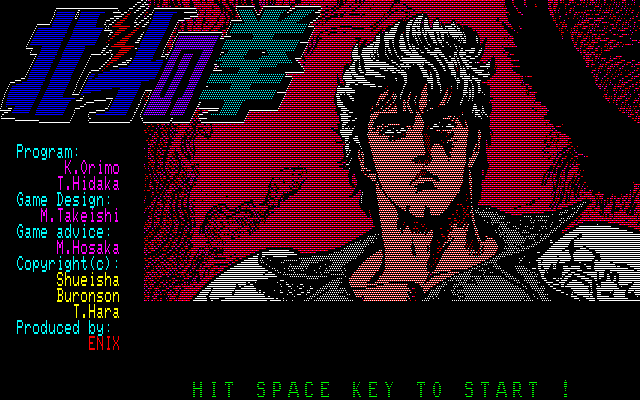

Enix's list of '80s PC games goes on and on, unknown in the west. Enix published the first videogame adaptation of Fist of the North Star, the famously ultraviolent post-apocalyptic battle manga (you may know it from the "You are already dead" meme). There's Gandhara, a cute-but-simple action-RPG with shades of Zelda. There's E.V.O.: Search For Eden, which actually was released in North America. Except that was the Super Nintendo version, a platformer, while the original is an RPG.

"For me, it's like a small bubble in PC history, where we're not here to make money," Redon says. He describes Enix's philosophy as: "Please yourself. Make the game you want to do, and we will publish it."

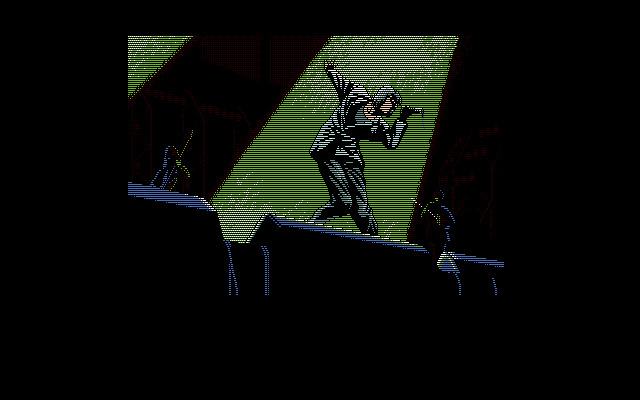

Game Arts: The tech wizards

While Enix released RPG and adventure after RPG and adventure, a small developer named Game Arts was doing things with PCs no one thought possible. They were making shooting games, and they were good. "They knew how to use the hardware, to push the limits," says Redon. Their first game was 1985's Thexder, a 2D platformer where you control a robot (which, of course, transforms into a jet) and fire a laser beam that undoubtedly blew the minds of kids used to visual novels.

Redon loves talking about shoot-em-ups, and describes Thexder's innovative shield mechanic in detail. You press a shield button to protect yourself for a few seconds, but timing it as enemies fire at you is critical, and your shield will collapse if you take too many hits. Choosing when to fight and when to run is more nuanced in Thexder than many similar games. Its follow-up, Silpheed, is even better (though it's hard as hell, and he still hasn't beaten it).

"Silpheed is only two disks. Really it's a marvel, that kind of game on only two discs," he says. "I think every byte was important. It's the best shooting game for the PC-88. The Mega CD version is not difficult [enough]. If you're a good player, you can beat it the very first day you buy it."

There's no crappy game from Game Arts. It's a team, from the beginning, of people who want to make great games.

Joseph Redon

At the time, most developers were releasing new games every few months. Silpheed was hyped up in magazines, but it took so long to finish, "people thought it would never come out and that for Game Arts, it's over," he says. "You have people to feed, a company to run. You don't put all your eggs in one basket and wait more than one year for a single title. But the game came out. And they wanted it to be perfect. So it was worth it." Silpheed is, notably, the first game to feature a digitized Japanese voice.

After Silpheed Game Arts made Zeliard, a platformer that actually made its way to the west for MS-DOS. Game Arts also made some Mahjong games with unusually advanced AI, starring parodies of popular '80s anime and manga characters. Soon after they'd transition to consoles and RPGs, with now-classics like Lunar and Grandia. But they left a mark on the PC in just a few short years. Game Arts even made a mahjong game that Redon holds up as a rarity from its era with genuinely good AI.

"There's no crappy game from Game Arts. It's a team, from the beginning, of people who want to make great games. They know what they want, and what is a good game. So I think they helped to really increase the quality of games on PC, and it's really a challenge to release a shooting game on a PC [at that time]."

Square: The hungry new kids

I couldn't fly 5,000 miles across the world, to an archive of thousands of obscure Japanese games, and not talk about Square. Anyone who likes Final Fantasy as much as I do inevitably digs into the developer's history to learn about some of its strange early games, like a Famicom RPG adaptation of Tom Sawyer. But in the beginning, like Enix and Game Arts, Square was all about the PC.

Its very first game was called The Death Trap, a silent 1984 text parser adventure with rudimentary art. "There is one very interesting thing about Death Trap: Until then, all adventure games in Japan, you had to type the commands in English," Redon says. "Death Trap was the very first one in Japan where you can not only enter your actions in Japanese, but also in English." And why were they English in the first place? "Because they were copying Apple II games," he quips.

1986's Alpha is notable for being an "eroge" or erotic adventure game from Square, but Cruise Chaser Blassty, released the same year, has more going for it. It's one of the first game designed by Final Fantasy creator Hironobu Sakaguchi, with Nobuo Uematu's first game music. And it's a mech sim, which is inherently cool.

Where Enix released excellent games throughout its entire PC life, Square was a humble developer until its big break with Final Fantasy. None of its PC games were big hits or left a lasting impression. But they do offer some insight into the truth behind the apocryphal legend that Final Fantasy's name came from Square's last-ditch effort to stay alive. Redon doesn't know if that's true, but he does have a theory.

"What you have to understand is that making a Famicom game—you needed to put cash on the table to get the license. It was $500 million yen. Huge. You had to put $5 million dollars on the table. So if they had decided not to release a Famicom game, they're okay. They couldn't fail. That's different. They were a recognised company, but they were clearly looking for a smash product."

The rest is history

It's been a long road for Redon to get where he is today, from a Japanese game-obsessed kid growing up in France to a fluent Japanese speaker, living in the country and turning that passion into a lifelong mission.

"This island is the worst place in the world for doing preservation," he says. It sounds like an exaggeration, but maybe it's not. On top of the earthquakes and other earthly dangers, Japan's copyright laws are draconian, and even the culture works against them. For many collectors, the concept of game preservation is to protect it from being released. A rare game isn't meant to be dumped online, but hoarded. For years, he's been slowly building up trust in the Japanese collecting community, convincing them that the Game Preservation Society can be trusted with Japan's gaming history.

The Society's games don't just sit on shelves—Redon is quick to distinguish preservation from hobbyist collecting. Each component is carefully stored separately. Glossy paper covers are slipped from their thick plastic cases and flattened in portfolios for easy browsing. Manuals and disks are stored separately, in special envelopes that won't damage the paper. It's all meticulously cataloged, boxes upon boxes lining cramped shelves, so Redon can look up a game in a database and pull each piece from its proper place.

We are going where no one is going.

Joseph Redon

It's an enormous effort, all made possible by donations and members who join the non-profit. All that money goes back into the archive: Running it, expanding it, and most importantly, paying volunteers to do the massive amount of work involved in digitizing magazines and covers and all the material related to these games. Redon admits he hasn't been great at spreading the word, and it can be hard to convince people to sign up when the Game Preservation Society's material largely isn't available online. But a public database is in the works, so that will hopefully change.

Seeing just a fraction of the games Redon has dedicated his adult life to preserving is a bit like opening Pandora's box: I know, now, how many games I wish I knew about but will never have the time or Japanese proficiency to play. It's also scary how perilous their survival is. Among all the retro game stores in Tokyo's Akihabara, only one, Beep, is dedicated to PC games. The owner is a member of the Game Preservation Society, and has helped Redon source some of the most obscure games in his archive.

There's simply less interest and nostalgia for this era of games, because their audience was never international. And when 50,000 sales is a major success, you can start to imagine how few copies of some of these games remain.

"We are going where no one is going," Redon says. "We are not only into PC games, we're into the preservation of games. Everything. But there are priorities. And the priority is stuff which is decaying very fast, stuff in which people have no interest, and stuff which is difficult to preserve."

In other words: Saving Japan's PC games, before they're forgotten or succumb to the bit rot that will eventually consume every disk, tape, and CD on Earth. Because, well, someone had to do it.

Subscribe to PC Gamer magazine

This article was originally published in PC Gamer UK issue 336. For more quality articles about all things PC gaming, you can subscribe now in the UK and the US.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).