Our Verdict

Clash’s brilliantly surreal world is hampered by uncompromising combat and level design.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A third-person brawling adventure from the makers of Zeno Clash and other oddities.

Expect to pay £25 / $30

Developer ACE Team

Publisher Nacon

Reviewed on RTX 2070, i7-10750H, 16GB RAM

Multiplayer? No

Steam Deck N/A

Link: Official site

Clash: Artifacts of Chaos is like the anti-God of War. It bears a family resemblance to Sony’s franchise revival, enough to invite comparison, but its design philosophy could hardly be more different. In particular, if you ever thought God of War would benefit from a more hands-off approach to nudging you through its adventures, then rest assured Clash keeps its sweaty palms strictly to itself.

If that sounds heavenly for those who prefer their games not to be littered with symbols and NPC chatter telling them where to go and how to get there, however, beware the old adage: "Be careful what you wish for, you might just get it." Pushing through Clash’s lush world and sprinkled narrative is often a richer experience due to the absence of supervisory noise. Yet it swings the pendulum of player guidance so far to the opposite extreme you may find yourself crying out for a quest marker or eager companion to show the way.

At times, it seems as though Chilean developer ACE Team really is making a point about God of War, not least because protagonist Pseudo almost seems to be a parody of Kratos, like the runt of the litter that the Greek champion emerged from. This nobody hermit is a misshapen muscle sack, all wonky shoulders and unevenly spread toes, whose bald head sticks out, literally, like a sore thumb. And while he shares Kratos’ gruff demeanour, he’s really a big softy, who sounds more like George Clooney than a battle-hardened warrior. His diminutive travelling companion, meanwhile, is a sort of spherical owl referred to only as ‘the boy’. Make of that what you will.

What is for sure is that the visual design of Pseudo and his homeland will only enhance ACE Team’s reputation for mind-popping surrealism, previously established in the Zeno Clash series (of which this is a continuation) and The Eternal Cylinder. The evocative oddness here is further enhanced by something Clash does have in common with God of War—a love of vibrant colour. Despite the AA production values, ACE makes its environments and their inhabitants sing by transforming them into coloured pencil drawings, decked out in bottomless hues and crosshatched shading. It’s a mesmerising effect (aside from an occasionally erratic framerate) that demands you drink in the green on every alien shrub you pass.

There’s a level of that colour in the story too, though more lowkey. Pseudo meets his companion by chance after the boy's grandfather is killed, and decides to help the little chap find refuge. When it turns out he's wanted by some shady characters, however, the two find themselves on an adventure. It’s a journey that takes them all around the land of Zenozoic, into factional territories and the paths of would-be bounty hunters. Much of the time here, might is right, so you have to fight for your interests, but Clash also uses its cast to mull over some fantastically twisted ideologies, including a memorable encounter with a group of fatalist thespians.

This is a sign that Clash wants you to think strategically before steaming in.

Whatever their role, the folk and wild animals you meet and battle are extraordinary to behold. Although, in the case of the people that’s often because they look like a series of back-fired experiments aimed at merging homo sapiens and beasts. They're chunky, rubbery beings with rough accents and faces that could find a home on Picasso’s Guernica. When the first one you meet, a stocky individual with his head squashed down into his torso, slaps his own face to prepare for battle, you know you’re in for a show.

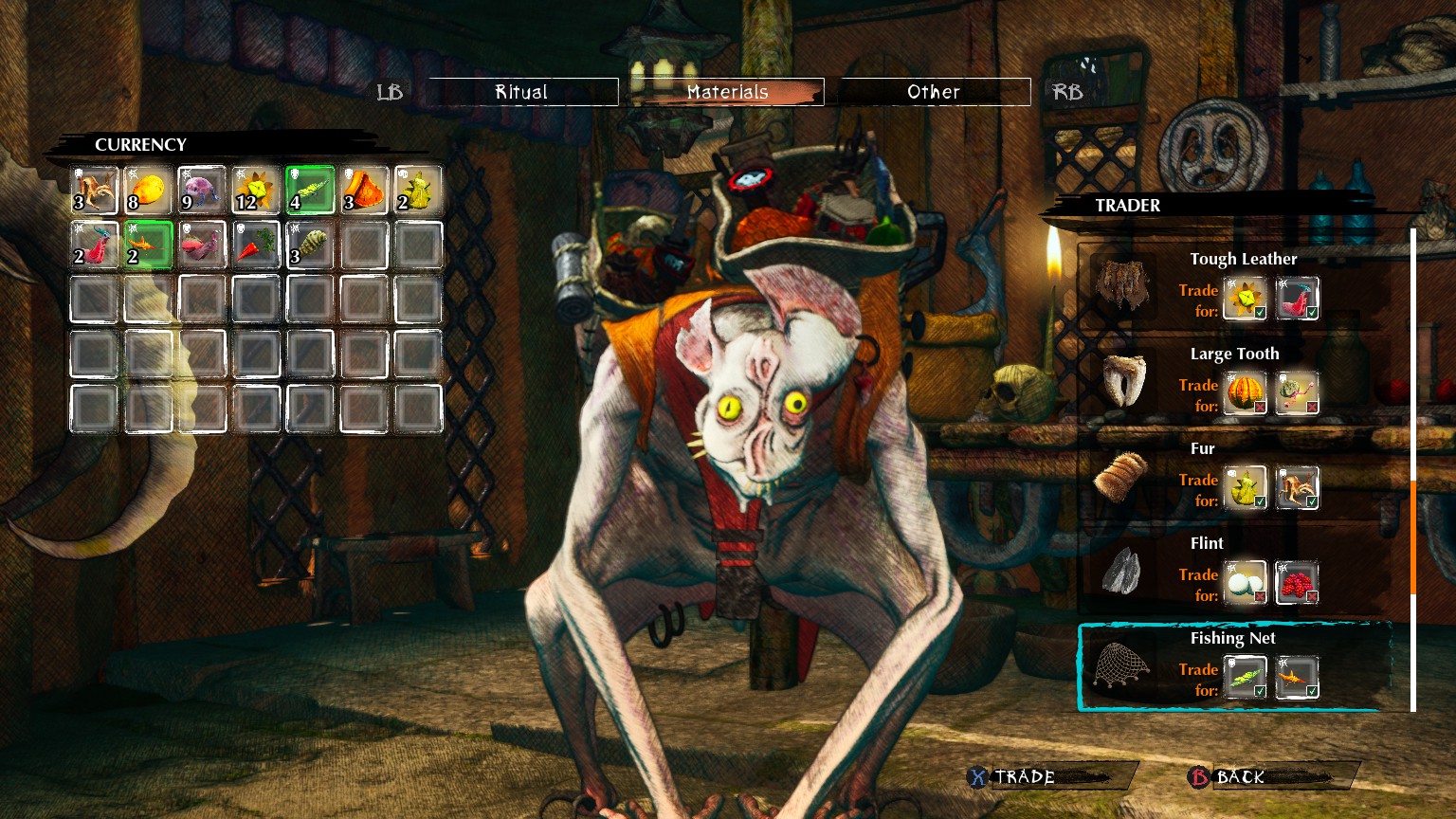

These encounters become more meaningful due to a ritual you can opt into before the fight kicks off. The ‘one law’ of the land is that any combat challenge must be accepted, with the two sides first playing a game of dice and the loser performing a forfeit of the winner’s choice. Maybe they have to drink a slow poison, for example, or are tethered to a peg with a rope, limiting their movement. Sometimes the results can be trivial but in others they can tip the balance in battle, and the ritual itself is a neatly tactical affair.

This is a sign that Clash wants you to think strategically before steaming in. The game’s first fights are like drunken bar fights, as you and a rival exchange blows with fat fists until one of you drops, or hilarity ensues as multiple opponents line up and accidentally slap each other. But as the game makes clear, most enemies are stronger than you, while you’re faster, so you soon have to play like a boxer punching above their weight, jabbing and retreating, or sidestepping swings to squeeze in a quick combo. In doing so, you build up a power metre which you can trigger when full to enter first-person mode (a call back to Zeno Clash), causing quick damage before executing a finishing move. Alternatively, you can wade in with weapons—mostly crude hammers and clubs—but they break after a while, and are often best saved for the toughest customers.

Despite the measured approach to hitting people Clash encourages, however, actually executing your plan is far less satisfying. Because you’re weaker than your opponents, small mistakes can be very costly, and because enemies are unpredictable it’s highly risky to get in close and rely on dodging or the spongy parry mechanic. You also can’t be certain when your attacks will interrupt theirs, so committing to a full combo is dangerous. Especially when outnumbered, your best bet is to circle at a distance, attacking with your projectile throw ability (an essential find) and baiting foes into hitting each other. The moment you try to land a strike, you risk getting blitzed.

The one mercy here is that when Pseudo dies, he reawakens at night in a body made of wood and nails and red woolly stuff, and this after dark form presents you with a second chance against those who bested you. If you can beat them, you can revive Pseudo’s flesh form and carry on your merry way. Fail on this second attempt, though, and it’s back to your last save point. It takes the edge off the frustration knowing you’ve got this backup shot, even if less punishing systems or flexible difficulty settings would be preferable.

Get lost

Unfortunately, this apparently open world is too knotted for its own good.

As for why Pseudo has a nocturnal timber alter-ego… well, one of Clash’s endearing qualities is that it doesn’t feel the need to explain. It’s a mysterious feature of a strange world that maybe gets clarified and maybe doesn’t, but either way adds to the sense that there’s more going on under the surface. That’s also a reason that Zenozoic is intriguing to venture into, even more so because you often get to navigate quietly, considering the lie of the land, contemplating what it all means. The boy breaks the silence occasionally, but doesn’t feel the need to fill every second with chat. It’s enough that the views are stunning, fading to pastel hues over long distances, and some of the music is hauntingly spiritual, a little like that in Nier: Automata.

Unfortunately, this apparently open world is too knotted for its own good. At first, it feels suffocating—a maze of dense paths carved into shin-high obstacles that signal invisible walls—only to spread out later in bewildering fashion, with no visual logic to prioritise one direction over another. Side paths lead to treasure, but also further side paths, branching off each other until you barely recall where you started, while main thoroughfares may be half-concealed, demanding repeated sweeps of an area to uncover. Locations lack the same intuitive connectivity as in something like Dark Souls, or the instantly distinctive geography, or unique shortcuts that help you mentally link the place together. You can spend a lot of time feeling lost in Clash, or erroneously looping back to where you’ve already been. I’ve stored pre-emptive sympathy for anyone who takes a break from playing it halfway through then tries to return.

Even the map is utterly hopeless—a small square on an inventory screen that takes six button presses to view. Pseudo appears on it as a tiny circle rather than an arrow, surrounded by nothing more than a handful of place names and vaguely sketched landmarks. That could work if the landscape consistently enabled you to see your destination in the distance, but it doesn’t. Fairly early in the game, for instance, you’re advised to head to ‘the town’, and there’s nothing that looks like a town visible on the horizon. Nor does it help much when you do get your bearings, because the route is unlikely to be a straight line.

Clash is almost offensively obtuse next to games like God of War, then, while its challenge level oscillates between a breeze and a gale. It also fails to either drip feed small rewards or produce a sense of achievement when you come through tough spots, since success often comes from attritional stubbornness. Yet there’s something to be said for Clash’s refusal to explain its ideas, places and oddball creatures the way God of War would. It’s more efficient in its world building, characterisation and plotting, and thus more generously open to interpretation. Pseudo may be Kratos’ smaller, weaker (and poorer) sibling, but at least he’s got a deeper and more interesting soul.

Clash’s brilliantly surreal world is hampered by uncompromising combat and level design.