Why I love setting videogame traps

And why I'm even quite fond of being on the receiving end.

In Why I Love, PC Gamer writers pick an aspect of PC gaming that they love and write about why it's brilliant. Today, Joe shares his love of laying traps—even when he winds up the bait.

As I lie crouched in the long grass next to a gathering of Sir, You Are Being Hunted's hostile robot pursuers, I'm transported back to my childhood. I'm back in the Glasgow housing scheme I spent the majority of my youth running around in, all the while hiding from gangs of tougher lads from neighbouring areas because I'm a shitbag, a fraidy cat, a chicken—similar to how I am now, neck-deep in reeds in one of Sir's procedurally-generated pastoral landscapes.

But this time it's different. This time it's all for the sake of bringing down a relentless automaton army, and I've got my tactics down to a tee. Ever read Sun Tzu's The Art of War? I did once, and while I struggle to see any credible correlation between the late military strategist's battle text and modern day entrepreneurialism, taken literally it's helping here. There's water at my back, a hillside flanking my left, and fences to my right. I'm all set for victory.

Until I stand in a bear trap. And not just any bear trap. My own fucking bear trap.

In an instant the gig is up, mechanical gunfire is rained upon me and, needless to say, my maker is very promptly met. I'll chalk this one up to yet another misadventure in my enduring relationship with videogame traps, and while I'd love to tell you I'll learn from my mistakes I almost certainly won't. I've been here before, you see, on several occasions.

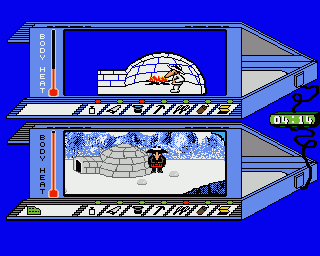

The first time I remember inadvertently blowing myself up with a self-set bomb was when playing Spy vs Spy on my dad's Atari ST in the early '90s. I was so taken with the idea of 'secretly' planting bombs in drawers for my splitscreen opponent to haphazardly stumble upon, that I'd often fill too many areas with traps and wind up catching myself out.

I spent years thereafter tracking games which offered similar levels of trap-based autonomy. Plenty of games throw traps at players as forms of obstacles, where they exist simply to be avoided or deactivated, but there's something magical about the ones which leave the responsibility with the player—be that in attack, defence, or, you know, reckless self-harm.

BioShock's plasmid system is a wonderful example of intuitive trap setting, whereby players can adopt a mix-and-match approach to the disposal of enemy splicers. Sure, taking them on head-first with melee and/or conventional weapons is the most obvious route to surviving Rapture, however the thrill of setting bad guys alight before sending a lightning bolt into the pool of water he or she is dousing the flames in is second to none. I once asked the game's lead designer Paul Hellquist why he thought setting virtual traps was such an enjoyable endeavour, to which he replied: "It makes the player feel smart."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

And, for me at least, that's exactly right. No matter how crude my plans ultimately play out, successfully snaring an unwitting opponent by way of a well-placed trap is an absolute joy. The first time I took down a Super Mutant in Fallout 3 involved me taunting the beast with some pithy pistol rounds, before leading it down a Vault 87 corridor towards a nearby succession of mines. I stood too close and was also offed in the blast radius, however was also delighted to thwart such a tough adversary—as bittersweet as this particular 'victory' was. Perhaps I'm not as smart as I think.

I performed this trick several times recently with Resident Evil 7's remote bombs, however perhaps the best instance of trap setting befalls Dishonored and its vermin-ridden Dunwall. By leveraging a combo of Corvo's Possession power and a spring razor, the masked protagonist can attach the trap to a rat, possess said rat, and lead set rat into a group of enemy sentries—breaking the possession at the last minute, just as the razor activates to devastating effect. Chain-linking this trait in Dishonored 2 yields some equally impressive effects, as does a number of the sequel's newly introduced powers.

Furthermore, contrary to well-thought out virtual trap laying, games like Orcs Must Die prove there is just as much fun to be had in mindless set ups—where the sole purpose of the game is using traps to simply thwart your enemies. It must be said that orcs get a pretty hard time across all game genres, but there is a lot of fun to be had in dropping them into tar pits or squishing them with spiked contraptions nevertheless.

Between being made to feel in smart and being offered choice, laying traps in games is an activity I'll never tire of. Be it in successfully defeating an irradiated monster, eliminating the white mouse with a well-place drawer bomb, or by standing in my own friggin bear traps—I'll continue to challenge game obstacles by thinking outside the box or die trying. Die and die and die trying.