US government deems it legal to circumvent DRM to repair electronic devices

A big win for consumers and the 'right to repair' movement.

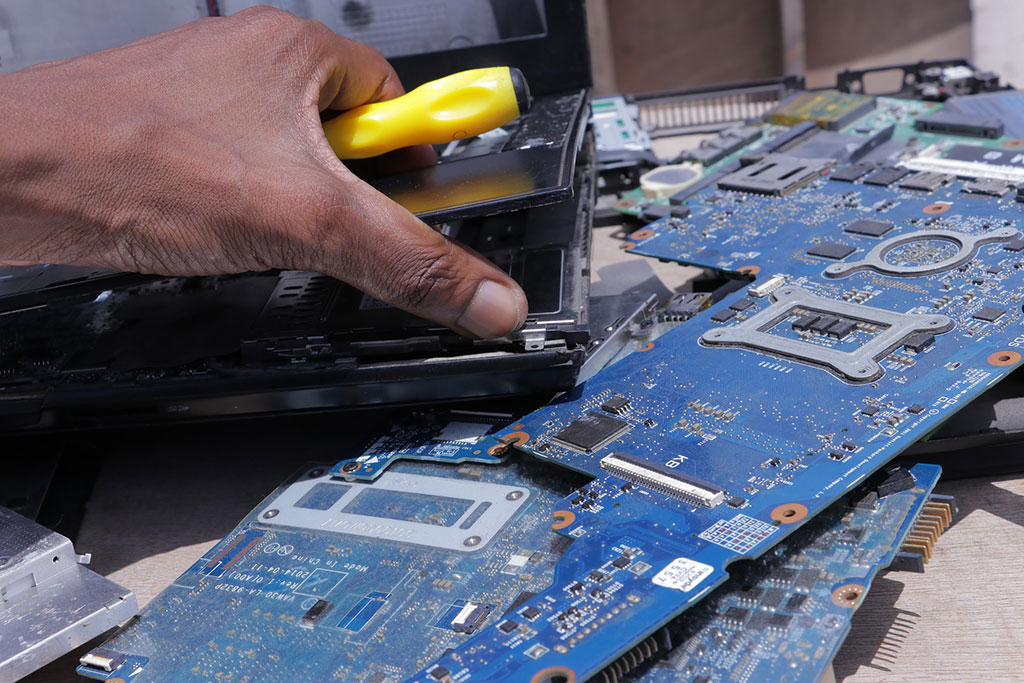

Digital rights management (DRM) schemes are not disappearing anytime soon, but your right to thwart these mechanisms in certain situations is being added to copyright law in the US, Motherboard reports. This effectively expands consumer protections when it comes to repairing and maintaining the original functionality of a host of electronic devices.

The Library of Congress and US Copyright Office outlined the new set of exemptions to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) in a "final rule" document (PDF) spanning 85 pages. In it are several new protections that legally allow consumers and repair shops to hack the firmware on devices like smartphones, tablets, smart TVs, mobile computing devices, and several other gadgets where technological protection measures (TPMs, but not the same as a Trusted Platform Module) stand between the consumer and a functioning product.

"The Acting Register recommended a new exemption allowing for the circumvention of TPMs restricting access to firmware that controls smartphones and home appliances and home systems for the purposes of diagnosis, maintenance, or repair," the document states.

Where necessary, the new rules give consumers the right to bypass DRM and TPMs in general for "the maintenance of a device or system... in order to make it work in accordance with its original specifications." It also protects consumers when breaking DRM is required to repair a device.

This doesn't mean it's now permissible to circumvent DRM in order to access other copyrighted works. In other words, this isn't the US government calling out DRM as evil and giving consumers a legal pass to do whatever they want with protected content.

However, the exemptions are broad and even covers "computer programs, where the circumvention is undertaken on a lawfully acquired device or machine on which the computer program operates, or is undertaken on a computer, computer system, or computer network on which the computer program operates with the authorization of the owner or operator of such computer, computer system, or computer network, solely for the purpose of good-faith security research and does not violate any applicable law, including without limitation the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986."

There's also a section on videogames that covers instances "when the copyright owner or its authorized representative has ceased to provide access to an external computer server necessary to facilitate an authentication process to enable gameplay."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

In such instances, a new exemption allows for "copying and modification of the computer program to restore access to the game for personal, local gameplay on a personal computer or video game console."

How this all works in practice remains to be seen. As Motherboard notes, there's nothing (yet) stopping manufacturers from being particularly devious with anti-repair mechanisms. For example, Apple built a kill switch into the MacBook Pro that stops the systems from functioning when it's been opened and repaired by someone who is not authorized to do so. The mechanism relies on embedded software that dials into Apple's servers to verify an authorized repair.

I'm not a lawyer, but the exemptions seem to say that users would be able to thwart the embedded software in that example. Unfortunately, having permission and the ability to do something don't always go hand-in-hand.

"Getting an exemption to reset the device is pretty different from having access to the firmware to actually do that," Nathan Proctor, head of US PIRG's right to repair campaign, told Motherboard.

That is true, but this is still an overall win for consumers, and a needed step in the right direction.

Paul has been playing PC games and raking his knuckles on computer hardware since the Commodore 64. He does not have any tattoos, but thinks it would be cool to get one that reads LOAD"*",8,1. In his off time, he rides motorcycles and wrestles alligators (only one of those is true).