Prison Architect: how Introversion avoided jail by embracing their hardest project yet

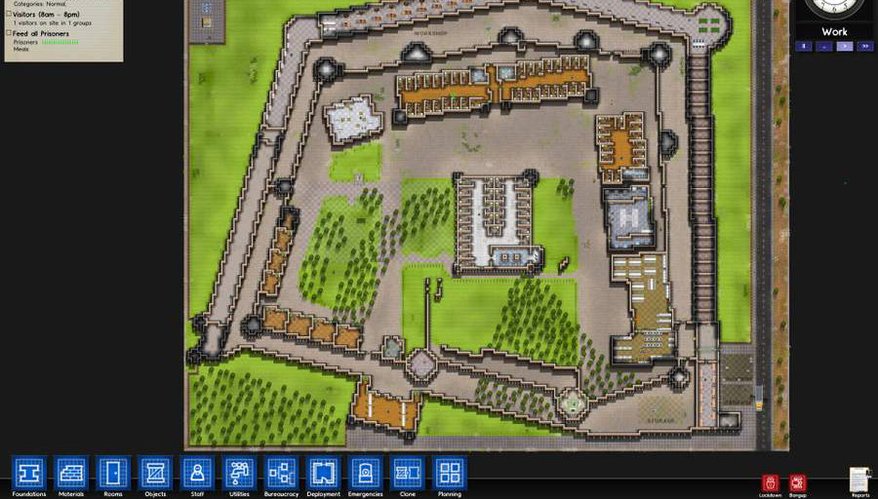

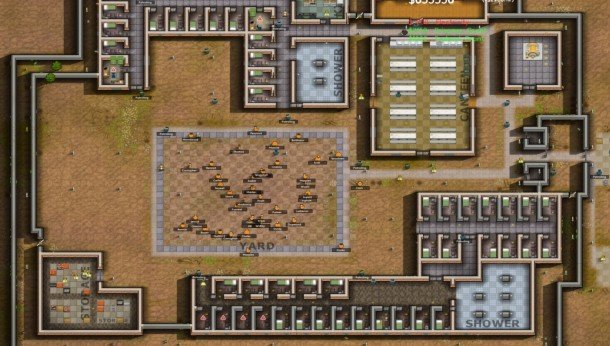

Right now, in alpha, the optimum strategy tends to change with each new version. “Everybody's got really into workshops,” says Chris. “They generate so much money, they keep your prisoners happy, and eventually they'll also give skills to your prisoners as well. So they're all good.”

This is one of the reasons why the revised contraband system is coming next. “Turn on the contraband overlay and you find that there are hacksaws and hammers and escape tools in the workshops in abundance, and that you can't possibly stop your prisoners from stealing them all, so you'll have that trade-off,” says Chris. “If you want to have an enormous prison workshop, you'll have to have a corresponding enormous security setup to stop the proliferation of tools and the digging of escape tunnels.”

If you do decide to build that enormous security setup, with metal detectors, dogs, and random searches, it will come with its own downsides. “More metal detectors and more dogs and more searches will piss off your prisoners and result in more trouble, so there's always going to be upward and downward pressure, and it should self-balance as a result.”

If all the talk of political ideology, race and simulation bias sounds grown-up, it's because Chris and Introversion are grown-ups. The game balances its dark subject matter with the cuteness of its sprites, and some humour. But for all the times when we think of indie development as being scrappy and punk - that Hotline Miami model of sloppy provocation - it's striking that Introversion have been doing this for almost 15 years. They are nearer to 40 than they are to their 20s. Two of the founders have children. They have mortgages.

It's taken a long time, then, but it's heartening that Prison Architect is Introversion's break-out game. Both because I'm talking to Chris from his home office and not a cell, but also because it means that indie development - the developers, the movement, the games themselves - are sustainable.

It's worrisome to consider how close Introversion came to collapsing. “When we were getting ready to close up and declare bankruptcy, I did actually apply for jobs at other games companies,” says Chris.

“I applied to Ninja Theory. Alas, I think I'm unemployable. I think they wrote a letter to me saying, 'although you've written a few indie games, we don't see how you're going to work in this big team.' I think they were probably right to be honest. I'm 35 now, the last time I had an actual job at a proper company I was 21. “Thankfully they said no, and that was when I decided I was going to stick it out with Introversion.”

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

This was in 2010. Development on Prison Architect started in September that year.