Our Verdict

A streamlined peep at the events which build up to Life is Strange. Emotionally satisfying, but sometimes clunky.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it A prequel to Life is Strange telling the story of one of its key relationships.

Expect to pay £14/$17

Developer Deck Nine

Publisher Square Enix

Reviewed on Windows 10, 16GB RAM, Intel Core i7-5820k, GeForce GTX 970

Multiplayer None

Link Official site

Third-person teen drama Life is Strange: Before the Storm has that challenge peculiar to prequels of having to provide the build-up to a story which managed fine without it. I’m playing and reviewing the three episodes of the Before the Storm miniseries having played and loved the original. That undoubtedly affects my thoughts about this game, so bear that in mind if you were thinking of playing them in timeline order rather than release order.

Before the Storm takes characters from Life is Strange and digs into their lives a few years prior. The main focus this time is Chloe Price; a gawky ball of unresolved grief, an exuder of teen rage and a serial player of hooky. We join her after the death of her father, William, just as class princess, Rachel Amber, crashes into her life.

To give a broad verdict for those who don’t want to risk spoilers, Before the Storm offers a more streamlined experience than its predecessor, prioritising conversation over puzzle-solving and fleshing out the relationship which is at the root of most of the action in Life is Strange. It leans harder into genre tropes and, as a result, its greatest strengths are intrinsically linked to its most pronounced weaknesses.

One of the things I loved about the original game was how it seemed to embrace the tropes of original teen fiction which used to rub along in subsections of fanfiction websites. That’s not a strand of fiction which usually gets space in gaming outside indie projects and I’ve seen it mocked and derided; lumped in with casual dismissals of everything on Tumblr.

That tranche of fiction can be overly dramatic, self-serving or steeped in wish fulfilment. Despite that (and because of that) you’ll also find spaces where people are figuring themselves out, writing their identities into being, having confrontations they can’t have in real life, conjuring up escapes from the frustration of adolescence, being their own heroes.

The first Life is Strange used that as the lens through which to unfurl its tale of gigantic storms and time jiggery-pokery. Before The Storm sees developer Deck Nine take up Dontnod’s tale. It offers a similar character-driven adventure with light puzzling but cranks the tropiness up and the game ends up better and worse than the original as a result.

I far prefer being Chloe to playing as Max. I like her anger and her action. I enjoyed hanging out with Rachel Amber and watching her relationship with Chloe erupt with the bewildering intensity I remember from being that age.

There are also some ace scenes—Chloe can have a foray into D&D which made me laugh out loud, there’s a people-watching improv segment which reminded me of doing the same thing with a friend I haven’t seen in years, and there are so many little moments of sincerity where the body language and the efforts of the characters to connect with each other feel just right.

There is also plenty of wish fulfilment. While Life is Strange wound its storytelling around a central mystery, Before the Storm hones in on Chloe and Rachel’s story. The first game (or at least my own canon playthrough) supported satisfying ambiguities with regard to relationships. This time I went headlong into romance. It was great. Dramatic and sincere and absolutely replete with moments designed to be screengrabbed, rendered as fan art or converted into gifs.

Girl aloud

Losing the storm story means the previous time rewind mechanic has been replaced with a backtalk challenge. In practice I found this to be a little hit and miss because you’re essentially arguing your way through a scene in a pretty artificial way. But it felt like a decent fit for Chloe’s character. Where Max is the exact sort of person who would want to painstakingly relive each and every moment to do the right thing and have the right answer, Chloe would definitely just shout at the problem until it stopped being a problem.

Then there are the segments where Before The Storm doesn’t exactly miss the mark, but I suspect playing it when I was 15 as opposed to in my 30s would have significantly altered my response.

Current Pip thinks that there’s definitely such a thing as too much pathetic fallacy. Current Pip is also burnt out on school plays as devices for teenagers to express their feelings, attractive people who don’t realise they’re attractive suddenly revealing an unlikely level of proficiency in some constructive or creative field, meaningful dream sequences, and conversations about starlight.

I do remember when those moments would have been just the right amount of over-the-top, but for me nowadays they tend towards heavy-handedness. (That said, I also stuffed my screenshot folder with moments from those sequences.)

That heavy-handedness also holds true when it comes to the more threatening moments in the game. They are in line with the rest of the drama but I found the relish in extreme expressions of bad situations uncomfortable.

I found my mind wandering during some scenes as conversations took on a stop-start quality

Partly that’s because Before the Storm sometimes wanders into simplistic melodrama with pantomime villains (as did its predecessor). But partly it’s because the game has played out against the backdrop of #MeToo. I’ve found it harder to watch violence and abuse in entertainment generally because of the relentless reminders of its presence in day-to-day life—they’re harder to separate. Life is Strange as a series also makes me let my guard down because I love those characters, so blows land that little bit harder.

On the overtly negative side, character movement—especially the running and walking animations—can be distractingly odd. In fact, characters generally have a very strange lack of physicality in the world. Sometimes that manifests as feet not seeming to interact with the ground, sometimes it’s a blow to an object which doesn’t make convincing contact. The body language itself manages to express some pretty subtle emotions, but it can struggle against this weirdly jerky movement in the characters.

Accompanying this is a stilted element of the dialogue—there are some unnaturally long pauses between lines and a propensity to tell not show. I found my mind wandering during some scenes as conversations took on a stop-start quality, maundered through exposition or were peppered with distracting animations.

Licensed content

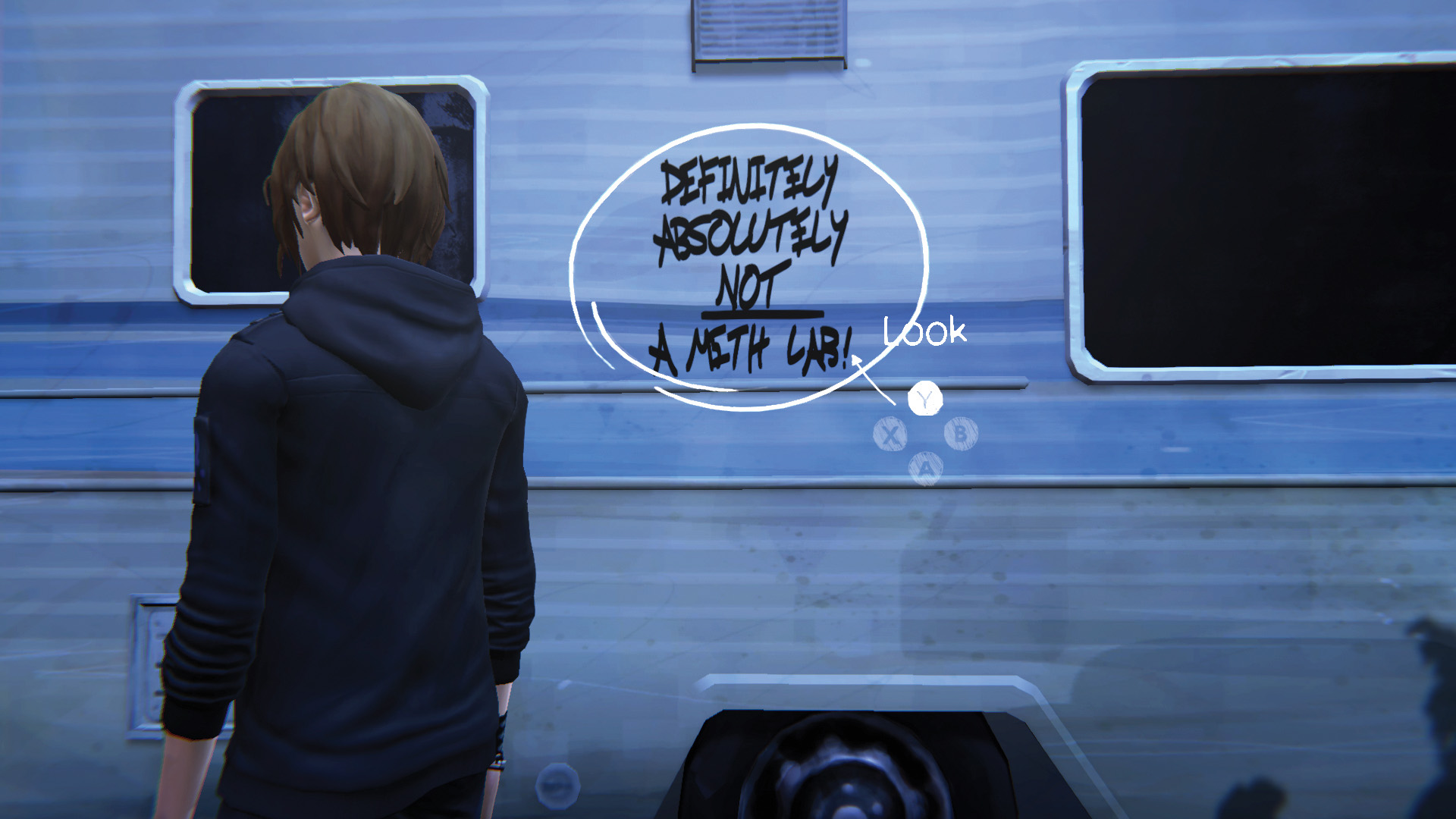

There are also moments which took me out of the game. Licence plates are the main offender here. It’s hard to concentrate fully on the opening scene where Chloe is playing chicken on the train tracks if you’re busy rolling your eyes at the ‘1337’ plate plonked on the front of the engine. Same goes for the ‘BRK BD’ plate on your dealer’s RV and a set of jokey plates on bikes you encounter early on.

Nods to and teasers for the original game are variable. Some add context to story and characters, others seem more about enticing players into picking up the other game. There are also points where coherence or logic are pushed to one side in service of emotions or aesthetic.

One minor example involves the repurposing of a night light which I suspect will only annoy me. A more significant example is the character of Chloe’s mum’s boyfriend, David. His alternating rudeness and vulnerability have been given no depth or coherence, serving only to augment, excuse or trigger situations with other characters. How my playthrough ended also doesn’t dovetail with Life is Strange.

Whether you are bothered by that will depend on how much disbelief you’re willing to suspend to get a pleasing aesthetic or emotional payoff.

One key difference between Life Is Strange and Before The Storm is that Chloe is now voiced by Rhianna DeVries instead of Ashly Burch. The change is a result of the SAG-AFTRA strike, which saw union voice actors take action in support of changes to how the games industry employs and pays them. SAG-AFTRA was pushing for secondary compensation, transparency about the nature of the work when signing contracts, and measures to help guard against injury during vocally stressful performances as part of their list of proposals.

Burch still participated in Before The Storm but as a consultant, helping shape and refine Chloe’s character and dialogue. The result is a performance I couldn’t actually distinguish from Burch’s Chloe.

Strike that

In terms of the game experience, that’s great. In terms of labour politics, the substitution muddies how I feel about the studio and the game. It’s worth reading the various interviews and points of view online to make up your own mind whether you want to support the studio and this outing for the franchise.

With that caveat in place, Before the Storm benefits from being more focused and more of a character piece than Life Is Strange. It gets rid of most of the clunky puzzling, provides emotional payoffs for Chloe fans, and puts a gay teenage girl front and centre in a valuable way.

A streamlined peep at the events which build up to Life is Strange. Emotionally satisfying, but sometimes clunky.