Is PC gaming for everyone yet?

Accessibility has come a long way, but it's still a work-in-progress.

This feature is part of PC Gamer's Accessibility Week, running from August 16, where we're exploring accessible games, hardware, mods and more.

Last year's installment of The Game Awards celebrated the first Innovation in Accessibility award. This was alongside numerous other events recognising accessibility for the first time, and dedicated efforts like the Video Game Accessibility Awards. It's a topic that's more visible than it's ever been, but does this reflect gaming generally?

While we might talk about some games as being 'accessible to new players' or an 'accessible entry point to a niche genre', accessibility here means access for disabled people—who make up 19% of working age adults in the UK, and 23.8% in the US [These figures have been updated to reflect more recent government reports]. So while mainstream games awards may have their flaws—rewarding some of the industry's darker aspects like crunch and abusive management—it's still meaningful when they recognise efforts to remove the barriers that might exclude us.

Accessibility doesn't only make things better for disabled players, however. David Tisserand, Ubisoft's senior accessibility manager, shared on Twitter that around 95% of players leave subtitles on when it's the default setting, and around 75% turn them on in the options at least once. This is a significantly higher percentage of the population than those who have hearing loss. Over email, Tisserand says, "for us, accessibility is about removing unintentional barriers so that as many players as possible can enjoy our games." And concerning subtitles, that includes people with difficulty processing audio, noisy roommates, babies they can't wake up, crunchy Doritos—the list goes on.

Ubisoft took two nominations for Innovation in Accessibility with Watch Dogs Legion and Assassins Creed Valhalla, but another nominee was Obsidian's early access survival game, Grounded. It sees players shrunk down to bite-size teen adventurers—a distinctly unnerving experience if the thing threatening to bite you is a spider. Grounded's Arachnophobia Safe Mode (or spider slider) made news last year for being the first game of its kind to buck the trend of forcing giant spiders on players with a phobia of them.

Grounded also highlights the way that accessibility can be enhanced in even its more basic structures, like its "talk to me" feature: a text-to-speech setting for its UI. As senior programmer Brian Macintosh explains, it wasn't initially his idea, but something publisher Xbox Game Studios encouraged. "I didn't initially understand how someone who is blind could even attempt to play Grounded, but it turns out there are many people who can see well enough to navigate the game world but have trouble reading text for vision or even cognitive reasons. For them, this feature takes the game from 'barely playable' to 'quite playable' which is a huge win."

"I didn't initially understand how someone who is blind could even attempt to play Grounded."

Brian Macintosh, Obsidian

Without downplaying the seriousness of phobias, most of us can relate to finding spiders unsettling—I used the slider myself when it turned out my tolerance for the critters strongly depended on our relative size being biased in my favour. While the spider slider is inarguably innovative, Grounded's text-to-speech option being a first for Obsidian represents something no less notable: disabled players who developers didn't expect to be playing their games are still being included.

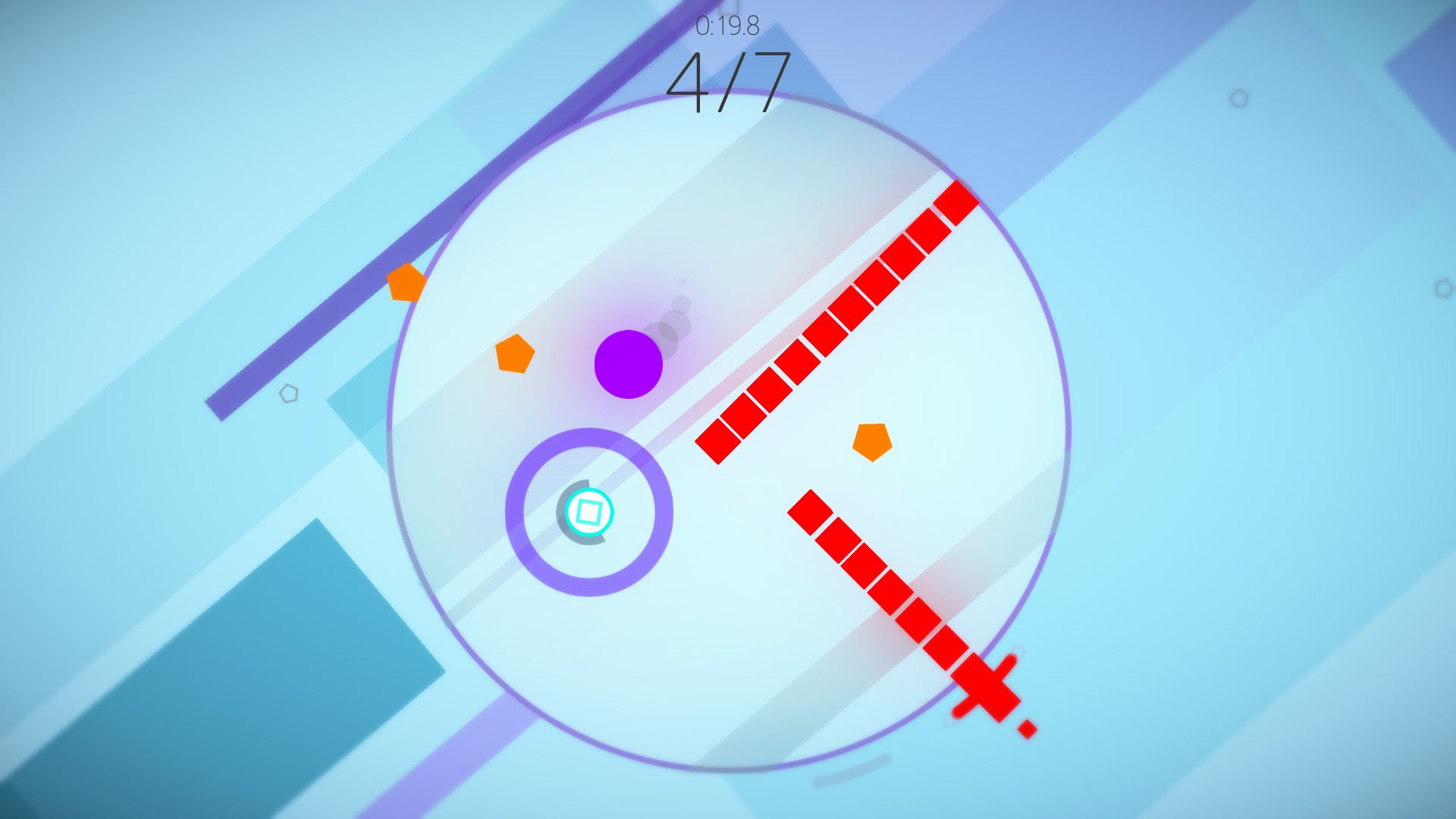

Beside industry giants Obsidian and Ubisoft, an unexpected nominee for 'Innovation in Accessibility' was indie creation HyperDot. The game features only one mechanic: to move, or more precisely, to dodge out of the way of the polygons flinging themselves at you at high speed. HyperDot's design was always centred around flexible approaches, but creator Charles McGregor credits a friend of his being gifted a Tobii Eye Tracker with the moment he realised he could make the game far more accessible.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"After I got [eye tracker compatibility] in there I was like 'Oh, if you can't hold a controller, if you have a motor disability, you would be able to actually play all of HyperDot with it', and that really was the start of, oh yeah, I'm going to actually take this a little bit more seriously and look into this." From there, his publisher Glitch supported him to reach out to accessibility consultant Cherry Thompson, as well as seek feedback from disabled streamers.

Watching streamers play the game was the first time McGregor had seen the game played outside of the build on his own computer. "Anytime that somebody couldn't play the game, whether it be a physical disability, or whether it be the game was just too challenging or something like that, that was just a gut punch, like 'Oh man I don't want you to not be able to play the game'. I think that that was a huge motivator for me." As a result, HyperDot offers support for seven unique controllers—including tilt and touch, as well as the eye tracking.

Support for alternative input is important because PC gaming is not, out of the box, accessible for everybody. Regardless of the content of any game, a mouse and keyboard can itself be a barrier. Alternative methods of input aren't a solution to inaccessible game design—but at the same time, even the best designed game is inaccessible if you can't use a PC. But, with PC gaming you can play with whatever peripherals you prefer, whether it's a glowing rainbow mouse or no mouse at all.

"Anytime that somebody couldn't play the game, whether it be a physical disability, or whether it be the game was just too challenging... that was just a gut punch."

Charles McGregor, Tribe Games

Charity AbleGamers helps connect disabled players with the assistive technology they may need to play. The mission statement on its website states: "Our mission is to enable play, in order to combat social isolation, foster inclusive communities, to improve the lives of people with disabilities." Disabled players can request support, and in return access individual peer counselling to help assess what they might need to adapt, with AbleGamers then also providing that equipment for those in financial need. The site also hosts a self-help library that breaks down what assistive technology is available for impairments such as gaming with one hand, or a visual impairment.

Technology solutions vary from specialist controllers (like the GrizPaw, which advertises being the fastest one-handed controller), to customising the Xbox Adaptive Controller with the best switches for your needs. As described by the AbleGamers site: "You can find switches for a variety of situations including, light touch, rigid, and even ones called 'twitch switches,' which can be placed on a muscle such as your calf or eyebrows."

There are also players for whom alternative forms of input don't make PC gaming more accessible at all, as it's the required posture that is the issue. "Because of POTS, sitting upright for long periods like you normally would in a desk chair can make me dizzy and tired," explains Els White, director of Spider Lily Studios, who keeps his chair reclined fully back, and has his monitor attached to an adjustable arm to tilt it in-line with his face. From this setup, he both plays games and works on his own. "My keyboard goes on a raised lap rest, and my mouse on a table beside me. Much easier on my heart!"

Accessibility isn't a one-size-fits-all solution, as not all disabled people have the same needs. For some, there aren't adjustments they can make—PC gaming is simply less accessible than the alternatives. "I tend to avoid PC games because after working all day at my computer, sitting there for even longer causes significant back and joint pain." Courtney Craven, editor in chief of accessibility review site Can I Play That? says they've also tried playing PC games with a controller instead of a mouse, "but that always seems to result in poor posture and again, more pain."

Issues like pain and other sensory and motor impairments are often the first thing we think of in terms of accessibility. But, like Grounded's Arachnophobia Safe Mode, Ikenfell makes space for inclusive mental health. Creator Chevy Ray says, "[o]ur sensitivity consultation team (Joanna Blackhart, Jeriko Green, & Aivi Tran) made a really good case for adding in an option to enable context-sensitive content warnings in the game."

These content warnings appear in-game and before skippable cutscenes that contain potentially triggering content, such as self-injury. "This is an extremely rare feature for any game to have, even in AAA companies that take accessibility very seriously. The feature has been immensely well-received, so I hope it's a feature more companies adopt in the future."

Ikenfell is a colourful turn-based tactical RPG about magical students, and pettable cats. Cast a multitude of spells, and hit the button at just the right time to land a great hit and do critical damage—or mitigate it, when you're defending. Notably, you can toggle how much timing affects gameplay (if at all). For players who would still find combat inaccessible, they would typically not be able to play the game—but in Ikenfell they can take the option to instantly win fights at any moment. "One of these options has them playing through the game and getting to experience the rest of its art, music, sounds, puzzles, and story," says Chevy Ray. "The other does not. I think it's probably quite obvious which of those two things I consider the superior choice."

"One of these options has them playing through the game and getting to experience the rest of its art, music, sounds, puzzles, and story. The other does not. I think it's probably quite obvious which of those two things I consider the superior choice."

Chevy Ray, Happy Ray Games

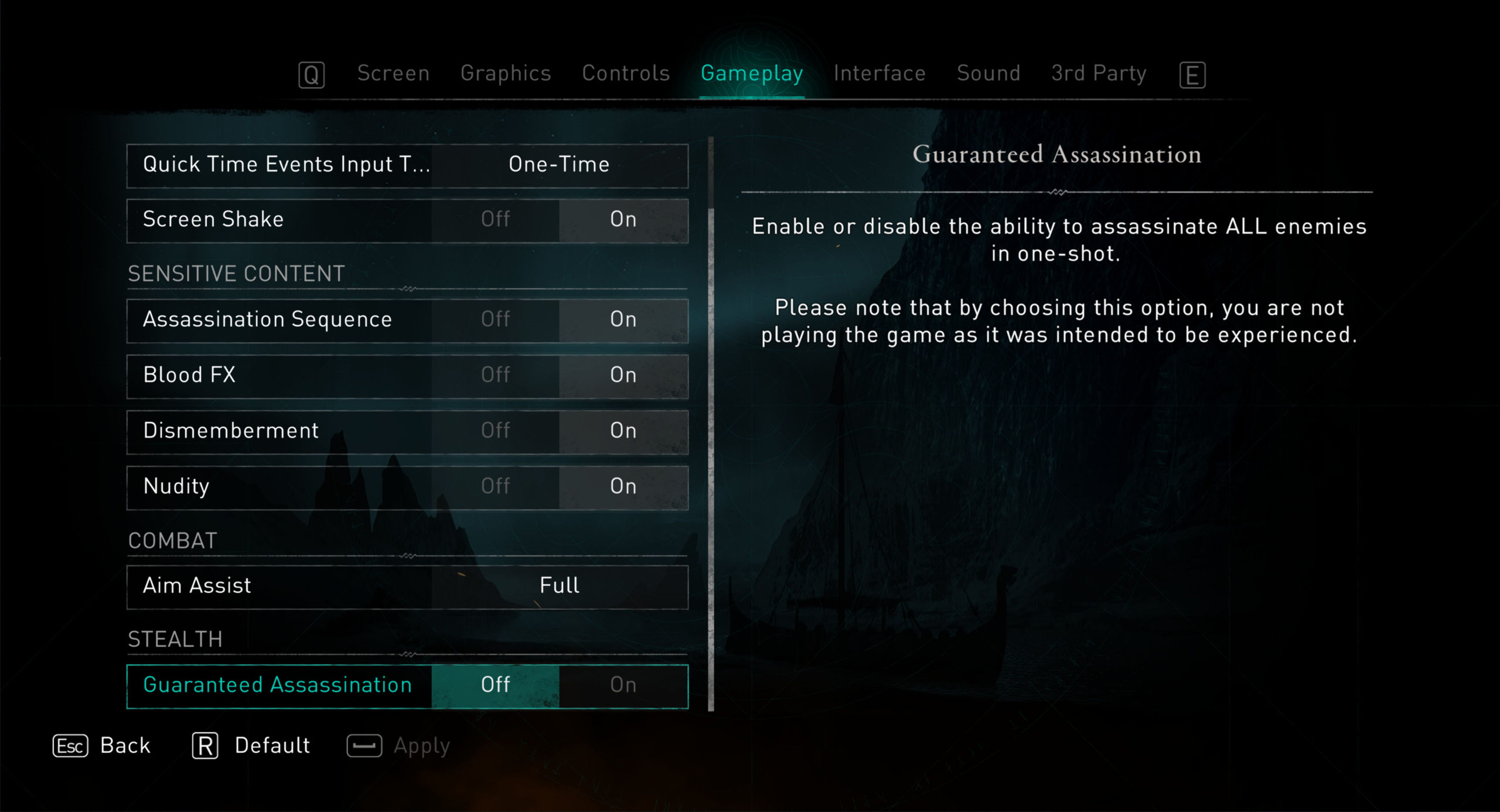

Ikenfell's skippable combat highlights the debate about the way games are 'supposed' to be played. Games that are well loved for being difficult—you know the ones—are often passionately defended by their fans because they're supposed to be so difficult. The mastery of the game, and its mechanics, are its own reward, and making any part of it skippable (or easier) in the name of accessibility would defeat the point, goes the argument.

A counterpoint: Frostpunk is a difficult game, and I've poured tens of hours into it trying to get the best possible outcome for every single campaign, for fun. When playing games like Dishonored, I set specific challenges—don't be seen and don't use powers and loot all the art, etc. I like being challenged, but that doesn't translate to, say, the precise timing required of Hollow Knight. The Mantis Lords move faster than I can see.

Difficulty is a broad concept, so it's hard to pin down how it relates to accessibility. When a specific barrier is making a game difficult, addressing that barrier is often a more straightforward solution. At the same time, what we think of as an 'easy mode' is a shorthand for a set of tools that reduces a game's demands. Those tools are still accessibility tools, particularly for players with chronic fatigue, pain, and/or impaired reflexes.

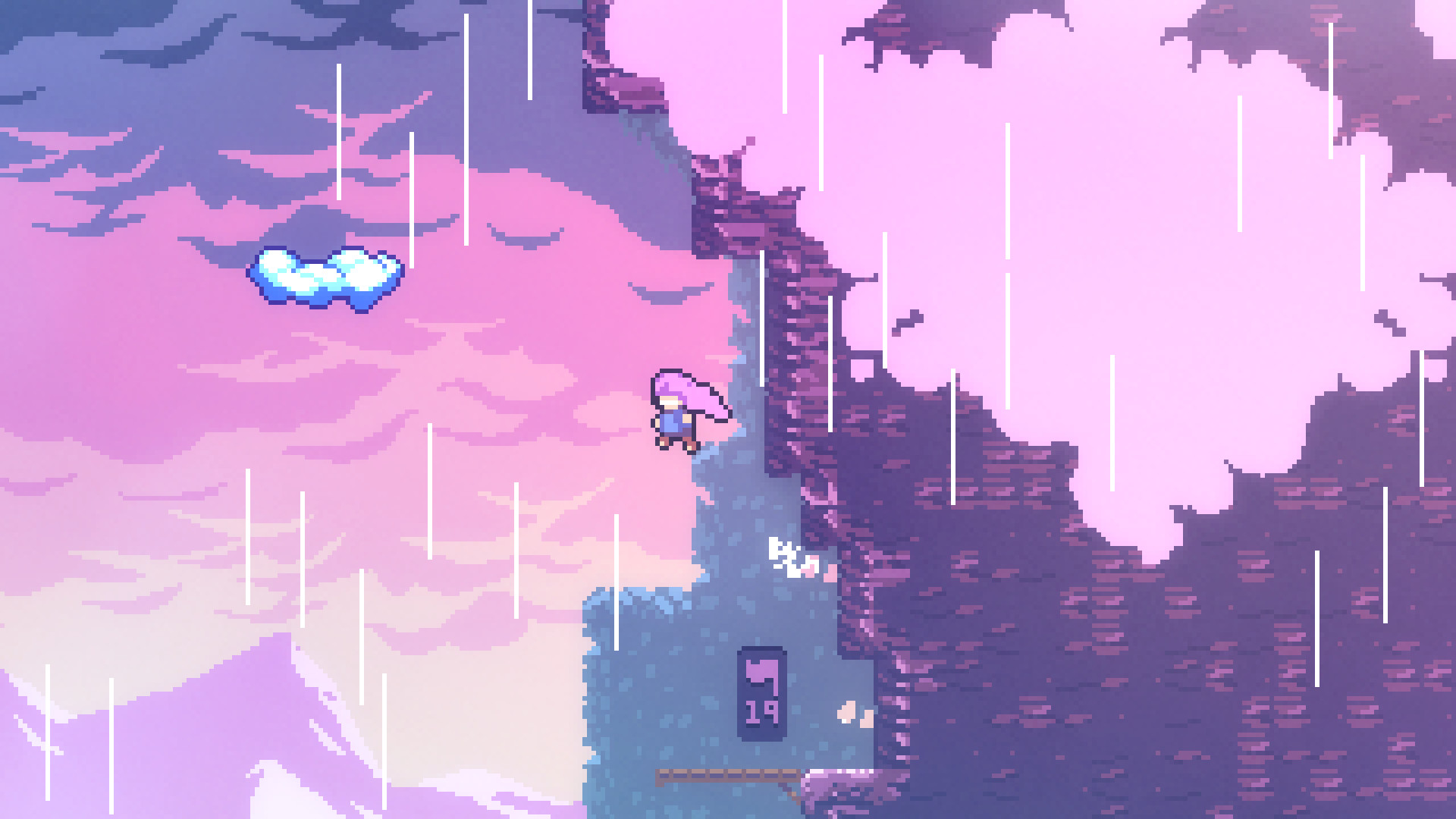

As an alternative, some difficult games in recent years have opted to implement Assist Modes—platformer Celeste's being one of the most well-known. Rather than dropping mechanical complexity by an arbitrary level, players can fine tune effects as needed like Madeline's stamina, or number of dashes, allowing the player more time to think or to course correct. Any Assist Mode is tailored for the gameplay it's accompanying—compare an invulnerable Madeline climbing through the murder-fungus to Control's Jesse, flinching with every bullet hit even when invincible.

Some players maintain that difficult games without any way to make them more accessible are 'the developer's vision', but accessibility specialist Ian Hamilton explains that this is one of the most common misconceptions that players have about how game development works.

"What designers have in mind for their players is really about an emotional experience. And that thing on the disc or that you've just downloaded is not the vision, it's not an experience in itself. It's just a means to an end, a framework put in place to try [to] let players have that kind of experience. The experience only comes into existence through interaction with the player—and players are a varied bunch, so whether what they experience matches the designer's intent depends on how that framework interacts with their own personal needs, abilities and preferences."

"What designers have in mind for their players is really about an emotional experience."

Ian Hamilton, accessibility specialist

'Difficult games' aren't a monolith, and no one game is difficult for the same reason as another. Whether it's to challenge players, for narrative theming, or to encourage players to fully juice a combat system, every difficult game wants the player to have a certain experience. That experience does not inherently need to leave out disabled players.

We might celebrate innovations in accessibility in games, but that only suggests that there are leaps and bounds to go—even if we are making them. "The state of the field is quite unrecognisable compared to even a few short years ago," Hamilton says, reflecting on his sixteen years of experience in the industry. "It wasn't long ago that a single mainstream game including a single accessibility accommodation was big news, and now it's hard to find any big name game that doesn't have a swathe of considerations, and indies are right there at the forefront of that progress.

"But we're still really only at the start. There hasn't yet been any AAA that has managed to nail all of the basics, things like remapping, subtitle presentation, colourblindness, text size, and effect/camera intensity. And we are a very, very long way from getting beyond that to where [we] really need to be, which is any gamer being able to pick up any game and have a reasonable expectation that they'll be able to play, that they won't be unnecessarily locked out or have an unnecessarily poor experience."

Right now, the PC gaming experience feels unpredictable when it comes to accessibility. I can pick up a physically undemanding adventure game and find myself waylaid by flashing lights and tiny tiny text, or demo an upcoming action game and find incredibly comprehensive difficulty settings. The one thing consistent with most people I spoke to, however, was that awareness of accessibility in development has increased hugely in only a short amount of time. Developers care, and there's a meaningful push for games to be more accessible and more inclusive. With the development cycle of games being the length it is, I'm excited to see what will be winning accessibility awards in 2022.