Brain-computer interfaces could revolutionise the way we live

If we can figure out what to do with them.

This article first appeared in PC Gamer magazine issue 532 in January 2021, as part of our 'Tech Report' series. Every month we explore and explain the latest technological advances in computing—from the wonderful to the truly weird—with help from the scientists, researchers, and engineers making it all happen.

A lot of sci-fi ideas seem to have their roots in the '70s. We don't know whether it's the availability of mind-bending drugs at the time, or the free love, or the fashions, but something seems to have sparked off a load of ideas that still seem modern today.

One of those ideas is the brain/computer interface (BCI), which you kind of expect Elon Musk to talk about in the same way he might discuss hollowing out a volcano, but sit up and take notice when Valve starts talking about it too. Research into them began in the '70s, and earlier this year the UK Government received a report into them from the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology, in which it was stated that entertainment companies are developing non-invasive BCIs "to play computer games". This no doubt made a few honourable members wonder what a ‘computer game' was, but the next sentence is even better: these products are currently being offered to consumers.

Non-invasive BCIs, which use sensors worn on the skull, are a world away from the invasive type Musk is implanting in the skulls of pigs, which he describes as "kind of like a Fitbit in your skull with tiny wires". We're not sure we'd want that, but for anyone who's suffered a disconnection between their brain and the rest of their body, perhaps as a result of an accident, an implant may be able to reconnect the nerve signals.

Take the case of two subjects in a recent DARPA-supported clinical trial carried out by the University of Melbourne, Australia. Both suffer from upper-limb paralysis thanks to ALS, also known as motor neurone disease, they were fitted with tiny wires that picked up electrical signals from the nervous system, and passed the results to a computer. This was able to distinguish between the different types of signals received when the subjects thought about different things, and these were mapped to various computer commands, including moving the mouse on an unmodified Windows 10 PC. By adding an eye-tracker, they were able to send messages, order online shopping, and use internet banking. They were then allowed to take the interfaces home, and achieved click-selection accuracy rates of over 92 percent. Sadly, there was no mention of whether they used this new ability to play StarCraft 2.

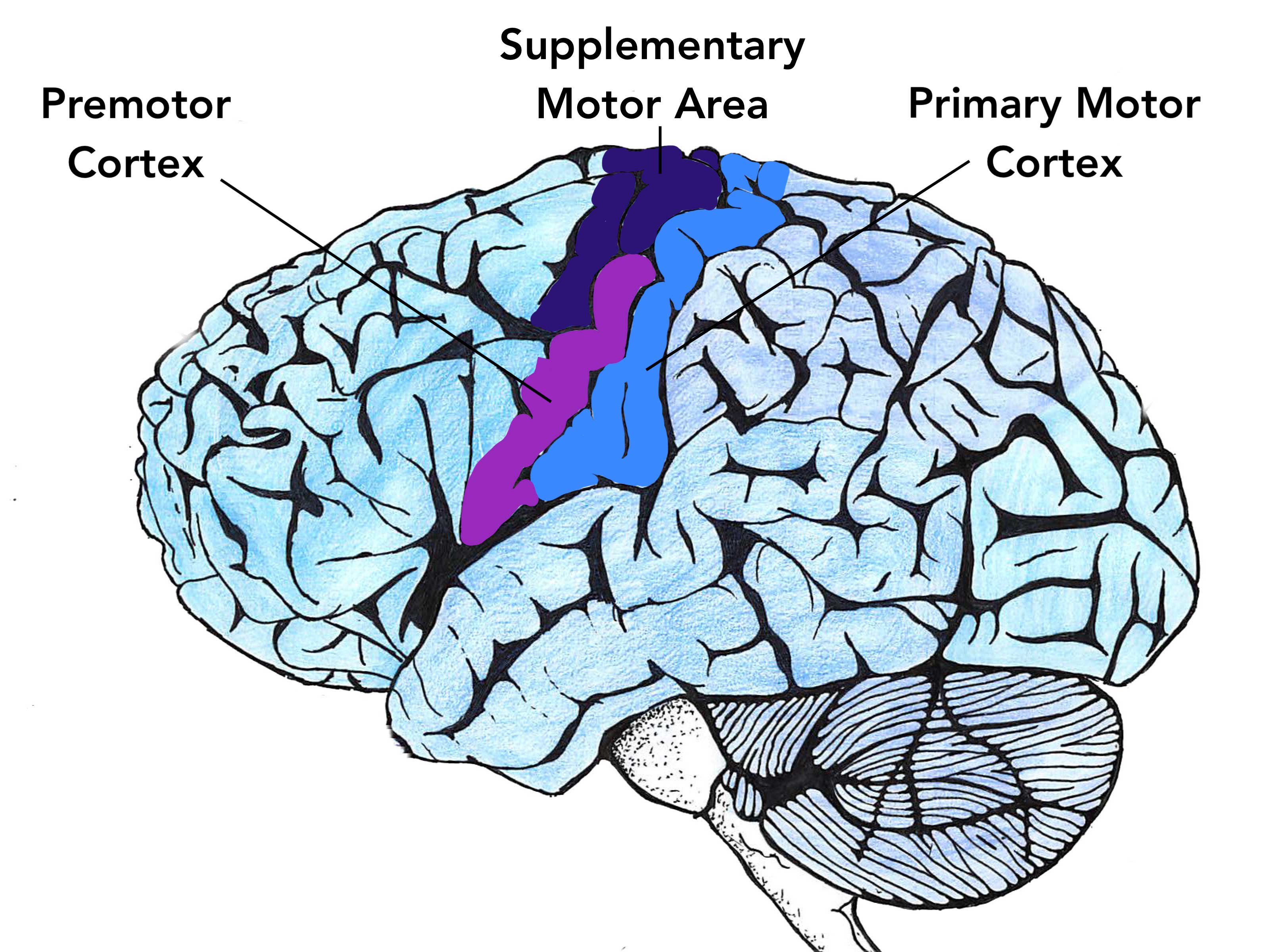

The surgery required for the interfaces is described as 'minimally invasive' by the study's authors, but still means wires in your brain—specifically the superior sagittal sinus adjacent to the primary motor cortex—inserted through veins using a tiny expandable tube called a stent. This is probably what Musk's pig has gone through too—although the South African-born billionaire suffered a blow in September when a survey suggested 90 percent of people wouldn't use one, with 32 percent worried it could be used for spying. The survey, carried out by OnBuy.com, was hardly scientifically rigorous, and Musk can take comfort in the 73 percent of respondents who claimed to be excited by the technology.

His firm, Neuralink, states its initial goals are similar to the Melbourne trial: to help people with paralysis to regain independence through the control of computers and mobile devices. Neuralink hopes to connect directly to thousands of neurons in the brain, sending the information to a computer where it's processed and initially used to control a mouse. This will be expanded, as the recipient becomes more skilled and the algorithms more tightly focused, to a keyboard, speech synthesis and—yes—a game controller.

Just because you're controlling a controller with your mind doesn't mean you'll be playing Doom Eternal all day, of course; they have other applications, perhaps tied into the control system of a motorised wheelchair. But it does open the door to brain-controlled gaming. Neuralink says it hopes to 'discover' non-medical uses for the technology.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Mind control

Controlling games with your brain isn't new. In 2010 a man was able to use an EEG (electroencephalogram) brain- scanning helmet known as the Berlin Brain-Computer Interface to play pinball (an Addams Family-themed table, for fans of spooky disembodied movement) at the CeBIT technology fair in Hannover, Germany. British company MyndPlay will sell you its MyndBand EEG headband, with three sensors that fit over your forehead, for £200, and there's an SDK for you to create something to use it with. Actual PC software seems a little sparse, however, with a mind-controlled media player, a rugby ball-kicking app and various quizzes the main events. There are also apps to train your brain, making yourself calmer, treating self-doubt, dealing with feelings of anger or guilt, and ones to help you meditate, rewarding you for entering a relaxed mental state.

It seems neural interfaces are here, and in the case of MyndPlay actually functional, but we're not quite sure what to do with them. The UK Government report mentions their use in therapy, as well as applications for marketing—gaining insights into consumer decision-making direct from the brain—and defence. There are also ethical considerations to be taken into account when fishing data directly from the living surface of our brains, and an ethical framework was published by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics in 2013, which deal with the effects the withdrawal of beneficial products may have on their former user, among other things, and that non-therapeutic devices must be regulated because they are likely to be used in private and without medical supervision. It recommended the European Commission regulate BCIs as medical devices no matter what their intended use.

When they break through to the mainstream, however, it remains to be seen if BCIs will be treated like Wi-Fi kettles—an amusing but largely unnecessary product with its roots in helping the disabled—or like VR, a more serious product that will continue to gain traction as the initial high prices come down. We wouldn't bet against the latter.

Ian Evenden has been doing this for far too long and should know better. The first issue of PC Gamer he read was probably issue 15, though it's a bit hazy, and there's nothing he doesn't know about tweaking interrupt requests for running Syndicate. He's worked for PC Format, Maximum PC, Edge, Creative Bloq, Gamesmaster, and anyone who'll have him. In his spare time he grows vegetables of prodigious size.