Losing it: Why bad players keep trying with good games

Raging against the machine

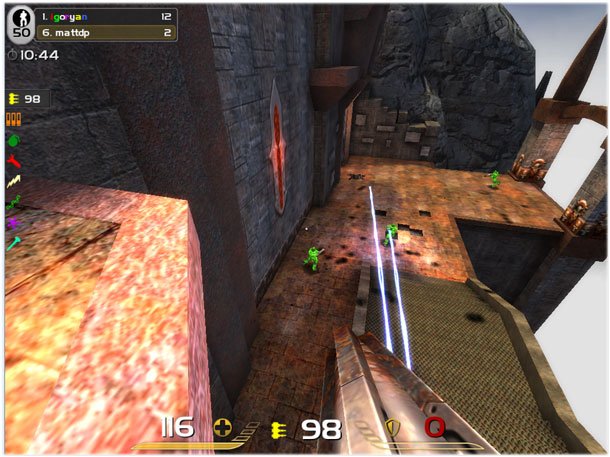

Lennart's explanation doesn't entirely explain why gamers like me, who'll simply never have the time or the reflexes to beat the teenage experts that throng the servers, continue to play in the face of repeated maulings. I know I'm a hopeless case, so it can't just be the lure of potential improvement that keeps me going.

What's particularly interesting is how this attitude contrasts with that engendered by overly difficult solo games. We've all played games with excessive learning curves and uneven difficulty spikes, and often the response is annoyance and frustration followed by throwing in the towel. It seems to me there must be something qualitatively different in playing against other people, but what?

Consalvo thinks that it might just be me. “I've known players that have attempted particular moves or levels in single player games up to 100 times,” she relates, “so we can't say they would just give up against the computer. It seems to depend on the persistence of the player and their investment in a particular game. Players will vary widely at their 'frustration point' where they will give up.”

Equally, some of those effects that make failure actively pleasurable when playing online also apply to the offline world. Nick Yee, a research scientist who's been studying online games for over a decade, points out that “it used to be near impossible to beat games. Most people who played Pac-Man or Tetris never beat the game, but they kept playing because it provided a challenge and allowed them to sense their own improvement.”

It's the same psychological feedback loop that we've already encountered. “Winning in itself isn't necessary to create engagement,” Nick says. “In fact, one could argue that not winning at Pac-Man and Tetris were precisely what kept people playing.”

Lennart, however, suggests it might be related to the unpredictability of a human opponent when compared to a bot. “If the standard of the [single-player] game is too high, the frustration threshold will be hard to overcome for players,” he tells me. “But against humans, the randomness of the opponent influences how we build our standard and makes it harder to form comparisons, essentially keeping us engaged for longer because we haven't yet met the standard that we rebuild every time we engage in gameplay.”

Friendship through failure

This was starting to chime a little better with my personal experience. Maybe the attraction is as simple as the humanizing element; the huge pull we have toward sharing activities, even if it's with faceless strangers who might be thousands of miles away and want nothing more than to repeatedly blow us to pieces.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Mia thinks that could well be the case. “Being social is not always about communicating—it is also about engaging in a shared activity with others,” she says. “Sometimes that means simply being among other people; it could mean engaging in a group quest or even PvP or other competitions.”

The point that you don't have to talk or even text with other players online in order to feel a sense of companionship from them is also one that Lennart makes. “They are just enjoying the company of other people and even if they could not communicate with other players directly, they are still enjoying the shared language of playing the game.”

Lennart and some colleagues ran a study on this hypothesis, analyzing several months of log files from a large site that matches players for online board and card games. They found that while user's behavior mirrored many aspects of real-life socialization, they were forming only transient relationships and talking very little. What could explain their actions?

“The main point here is that games themselves are a form of communication,” he tells me. “They allow us to communicate with other humans by monitoring and comparing our behaviors in the game to others and witnessing personal growth in an easy to understand constrained environment. Games, even the competitive ones, are in my opinion one of the most social ways we can interact using technology today.”

And there's my answer. I play a lot of board and card games, and have long been aware that a big part of the draw for me is the enjoying the company of friends and family and gaming at the same time. I'm no good at those games either, but I do have a fantastic repertoire of funny stories about my spectacular failures.

So I'm happy to carry on being the bottom of the pile just to have the pleasure of knowing that behind all the nicknames on top of me are real people, and I've contributed to their game, their narrative, their own repertoire of anecdotes. Whatever my losses in the game, I've won a little victory in my real world life.