Why game devs were right to ridicule DirectX co-creator's article glorifying "crunch"

DirectX co-creator and co-founder of the WildTangent gaming network

Alex St. John has been in the games business for a long time now. He's one of the creators of Microsoft's DirectX platform, he co-founded WildTangent, and served as the president of the social networking/online gaming site Hi5. So he's plenty familiar with the ways the industry works. Which goes a long way toward explaining the angry reaction to a recent opinion piece he penned for VentureBeat, in which he accused game developers of adopting a “wage-slave attitude” because they had the temerity to expect to be paid fairly for the work they're contracted to do.

The crux of his article centers on “crunch,” those long stretches of outrageous hours that developers are often forced to undertake in order to just get a game out on, or at least near, schedule—often without being paid for the overtime hours. It's been an issue for ages; developer and writer Erin Hoffman dragged the problem into the light all the way back in 2004 as “EA Spouse,” when she wrote about the long, disruptive hours being put in by her husband, who at the time worked for EA. But it's still an all too common industry practice.

And that's how it should be, according to St. John. “Every legendary game developer I’ve ever known pursued gaming as a vocation out of sheer passion. Most could have made more money, had more security, lived more “balanced lives” in other tech jobs, but they wanted to make games and they pursued it 110 percent all the time. Not a single person I have ever known who went on to greatness in the gaming industry has ever exhibited a shred of wage-slavishness,” he wrote. “Making games is not a job—it’s an art.”

"You need to get an actual job producing productivity software if you want to be paid 'fairly' and go home at 5 p.m."

“There’s no amount of money that anybody can pay people with a wage-slave attitude to let it go and put themselves completely into a great game. There’s nothing that can compensate people 'fairly' for the sacrifices that great art requires. It’s art. You need to get an actual job producing productivity software if you want to be paid 'fairly' and go home at 5 p.m. Anybody good enough to get hired to write games can get paid more to work on something else. If working on a game for 80 hours a week for months at a time seems 'strenuous' to you … practice more until you’re better at it. Making games is not a job, pushing a mouse is not a hardship, it’s the most amazing opportunity you can possibly get paid to pursue... start believing it, and you’ll discover that you are even better at it.”

It's telling that St. John felt the need to put “fairly” into quotes, the obvious implication being that he believes the pay-for-work-performed social contract is evidence of a character flaw in the worker rather than just, you know... fair. And yet somehow, that manages to not be the most ridiculous thing he argues in the article; your mileage may vary, but I'd say his suggestion that 15-hour workdays (for employers who are generous enough to allow for Sundays off) over the course of multiple months is not “strenuous” tops the list.

Game dev disagrees

Lots of readers disagreed vehemently and vocally with St. John's screed, but one particularly noteworthy response came from Rami Ismail, one-half of indie studio Vlambeer, whose games include Super Crate Box, Ridiculous Fishing, Nuclear Throne, Serious Sam: The Random Encounter, and my favorite, Luftrausers. His “inline response” to the article made a number of valid criticisms of St. John's idea of the ideal employee, but there's one line in particular that really nails it: “Your complaint here is literally that someone asked to be paid fairly.”

Co-founder, Vlambeer: Ridiculous Fishing, Luftrausers, Nuclear Throne

“Great games can be made by giving them everything you’ve got and more, and great studios and developers are made by not burning the fuck out. Turns out great studios and developers make better games, because they have more experience that they can apply because they did not burn the fuck out,” he wrote. “Wage-slave attitude just means ‘employee’ here and thank you very much but those hundreds of ‘wage-slaves’ that work on each AAA title deserve not just our utmost respect, but also reasonable wages and working hours.”

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Loving your job is great—vital, even—but it doesn't change the fact if you're putting in 80-hour weeks as a regular thing, you are going to suffer for it, and ultimately, so is your work. But it's difficult to overcome an “addiction” to crunch because, as this Kotaku article from last year points out, it feeds on itself: Results achieved through a horrific period of crunch become the benchmark for future projects, so what should have become an exceptional one-off instead becomes the norm.

“I tell you here and now: Structural crunch is bad, and burning out is real."

The face-slapping irony is that St. John's career at Microsoft came to an end, according to this Information Technology Leaders bio, because of burnout. “St. John started to burn out. He would pass out at his keyboard and straggle into morning meetings with key marks on his face,” it says. “Work sucked everything out of him; his marriage disintegrated. In 1997, he succeeded in getting himself fired, as he tells it, 'and walked out of Microsoft feeling 100 lbs. lighter.'"

St. John addressed that apparent dichotomy in a follow-up post on his personal blog, in which he said that he and “thousands of other kids” made millions working years of 120-hour weeks at Microsoft. “What’s sad is that all of these successful people don’t talk about the values that got them there because they don’t need the hassle of being screamed down for being 'wealthy beyond good taste',” he wrote. “When did it become gouache [sic] for successful people to talk about what they really did and valued to achieve success?”

That's a fair question, and there are certainly people who are willing to, and even want to, put in crazy kinds of hours on projects they feel passionately about. But St. John appears to be missing an important point: His stint at Microsoft was self-destructive, but also extremely lucrative; he made sacrifices, and earned millions. Yet in his VentureBeat article, he specifically criticizes game industry employees “whining... about not being paid fairly by some big employer.” In other words, for asking for precisely what he got—in principle, if not in straight-up dollars—for what he did.

That's why the near-universal rejection of St. John's ridiculous assertion by those working in development today was so welcome and important. Video games can be art, and the creation of art can be its own reward. But it's also a big, booming business that employs thousands of people. I have no doubt that a lot of the people who work at those outfits—maybe most of them!—love what they do. But a lot has changed over the past 25 years, and the self-flagellating nonsense that may have seemed reasonable when a half-dozen guys were making Wolfenstein 3D just doesn't hold water when a game like Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare takes that number of entire studios to create.

It all reminds me of Harlan Ellison's famous “Pay the Writer” rant from several years ago, in which the famed author and hothead went on a tear about being asked to contribute work to a Babylon 5 DVD set without being paid. The subject was different—he was specifically angry about writers not being paid, and not demanding to be paid, for their work—but the bottom line is much the same: People are entitled to fair pay for work performed. You would not, as he says, ask your doctor to take out your spleen for nothing. So why would you criticize employees at a major game studio for not wanting to put in untold hours of unpaid work?

"Real engineers don't value money... The money is for the wife or GF."

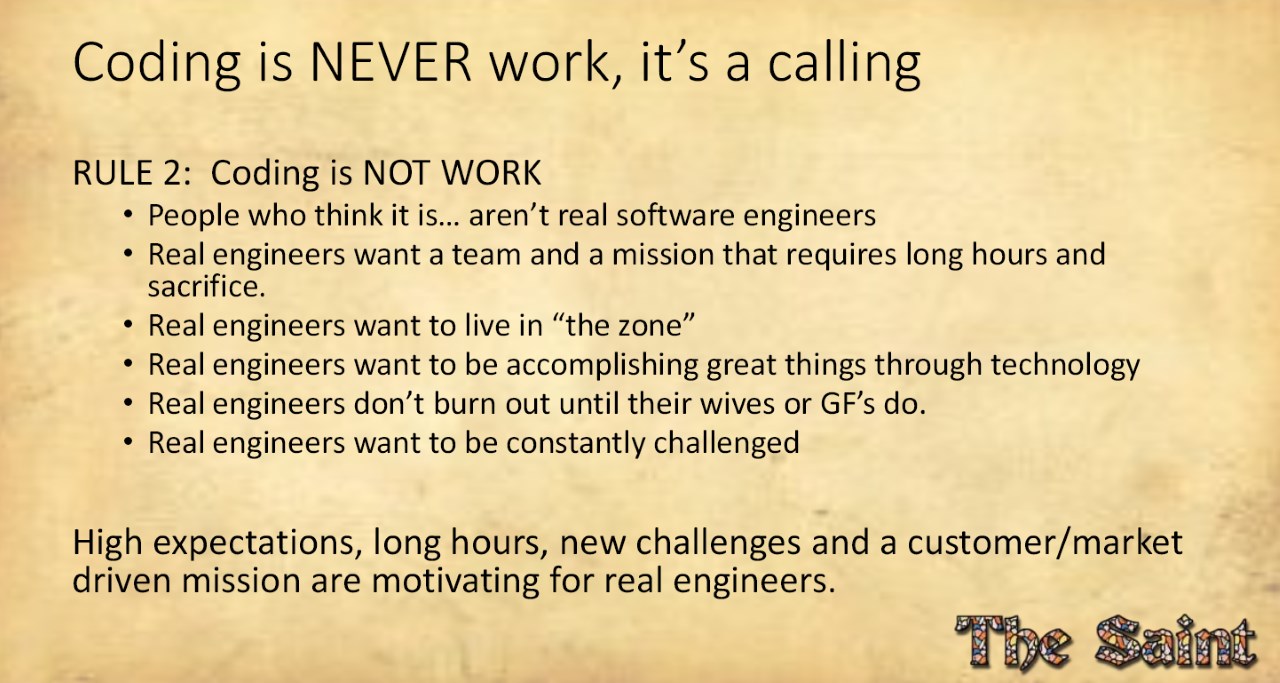

St. John's blog post doubles down on his criticism of “lazy millennial hipster game developers” who are “upset at the suggestion that 'Thinking' isn’t really hard work.” But while there's no denying that ambition and drive can be valuable character traits, a PDF presentation on his site entitled “Recruiting, Training, and Retaining Giants” suggest his attitude towards employees is deeply troubling, and arguably grotesque. Its snippets of management wisdom include gems like, “Real engineers don't burn out until their wives or GFs do,” “Real engineers don't value money (the money is for the wife or GF),” “Work them 'too hard' it's good for them and the only way they get seasoned,” and best of all, “Be on the lookout for the holy grail... the undiscovered Asperger's engineer. (They work like machines, don't engage in politics, don't develop attitudes, and never change jobs.)”

Taken as a whole, it's a startlingly retrograde attitude toward productivity that would be hilarious if it didn't have a very real, very negative impact on the lives of actual people. And maybe treating workers like pack mules gets the job done, in some imperfect way, at large studios where employees come and go in an endless, anonymous ebb and flow. But for people who view working in the games industry as a long-term career option and not just something to do until something better comes along, Ismail has the right of it.

“I tell you here and now: structural crunch is bad, and burning out is real,” he wrote. “I hope you’ll take care of yourself, so we can have you and your games and your experience around in this industry for many more years to come. Whether it’s as a 9-to-5 employee making AAA games, a legendary developer, an indie working on their first games, or a part-time developer that makes games for fun. Be passionate. Make games. But please take care of you.”

Andy has been gaming on PCs from the very beginning, starting as a youngster with text adventures and primitive action games on a cassette-based TRS80. From there he graduated to the glory days of Sierra Online adventures and Microprose sims, ran a local BBS, learned how to build PCs, and developed a longstanding love of RPGs, immersive sims, and shooters. He began writing videogame news in 2007 for The Escapist and somehow managed to avoid getting fired until 2014, when he joined the storied ranks of PC Gamer. He covers all aspects of the industry, from new game announcements and patch notes to legal disputes, Twitch beefs, esports, and Henry Cavill. Lots of Henry Cavill.