The making of Undertale

Conflict, comedy and creature comforts: how a rule-breaking debut became an unexpected phenomenon

The authority on videogame art, design and play, Edge is the must-have companion for game industry professionals, aspiring game-makers and super-committed hobbyists. You can subscribe to both the print or digital editions here. Edge 319 features Dark Souls Remastered on the cover and is available now.

Welcome to the first guest article from Edge on PC Gamer, where we'll occasionally feature PC gaming-related articles from the long-running magazine's recent history. This was originally published in Edge 314 in December 2017, and is republished here with the Edge team's permission.

Toby Fox was almost two-and-a-half years old in March 1994, the month Edge’s infamous Doom review was published. Outwardly, there would seem to be little to connect those two facts. But to play Undertale is to find a game that seems to have spawned from the same line of thinking as that oft-misquoted conclusion: “If only you could talk to these creatures, then perhaps you could try and make friends with them, form alliances... Now, that would be interesting.” Indeed, when Fox was looking to raise funds to continue the development of Undertale, the modest description he chose for the Kickstarter page posited it as ‘a traditional roleplaying game where no one has to get hurt.’ In truth, his game was anything but traditional, although he got the second part right. You can befriend, rather than fight, the game’s bosses. For once, you can talk to these creatures.

The ironic twist is that the first seeds of Undertale were sown from conflict, growing from a battle system Fox had programmed in GameMaker Studio. In fact, his initial inspiration for this early experiment came while he was casually browsing Wikipedia. “One day, I randomly read about arrays, and realised I could program a text system using them,” he tells us. “So I decided to make a battle system using that text system, which in turn gave me many ideas for a game. Then I decided to make a demo of that game – to see if people liked it, and if it was humanly possible to create.”

Undertale’s combination of turn-based combat and realtime elements had plenty of antecedents, though it has more in common with another genre entirely, with danmaku shooter series Touhou Project an inspiration. “I wanted to do something different from what I was already familiar with,” Fox says. “I mean, something novel is generally more interesting to people than something they’ve seen before. Also, bullets offer more variety in movement than simple button presses.” Rather than study any particular games to get an idea of rhythms and patterns, it was an iterative process: he’d adjust his self-created designs until the encounters felt challenging but fair. The latter was vital: Fox didn’t want Undertale’s combat to be considered ‘bullet hell’, since he’d used fewer and larger projectiles to make it more approachable. “Undertale was made with the understanding that those types of games are generally too intimidating for most players. Maybe it could be called ‘bullet heaven’ or ‘Bullet Hell Jr’,” he suggests.

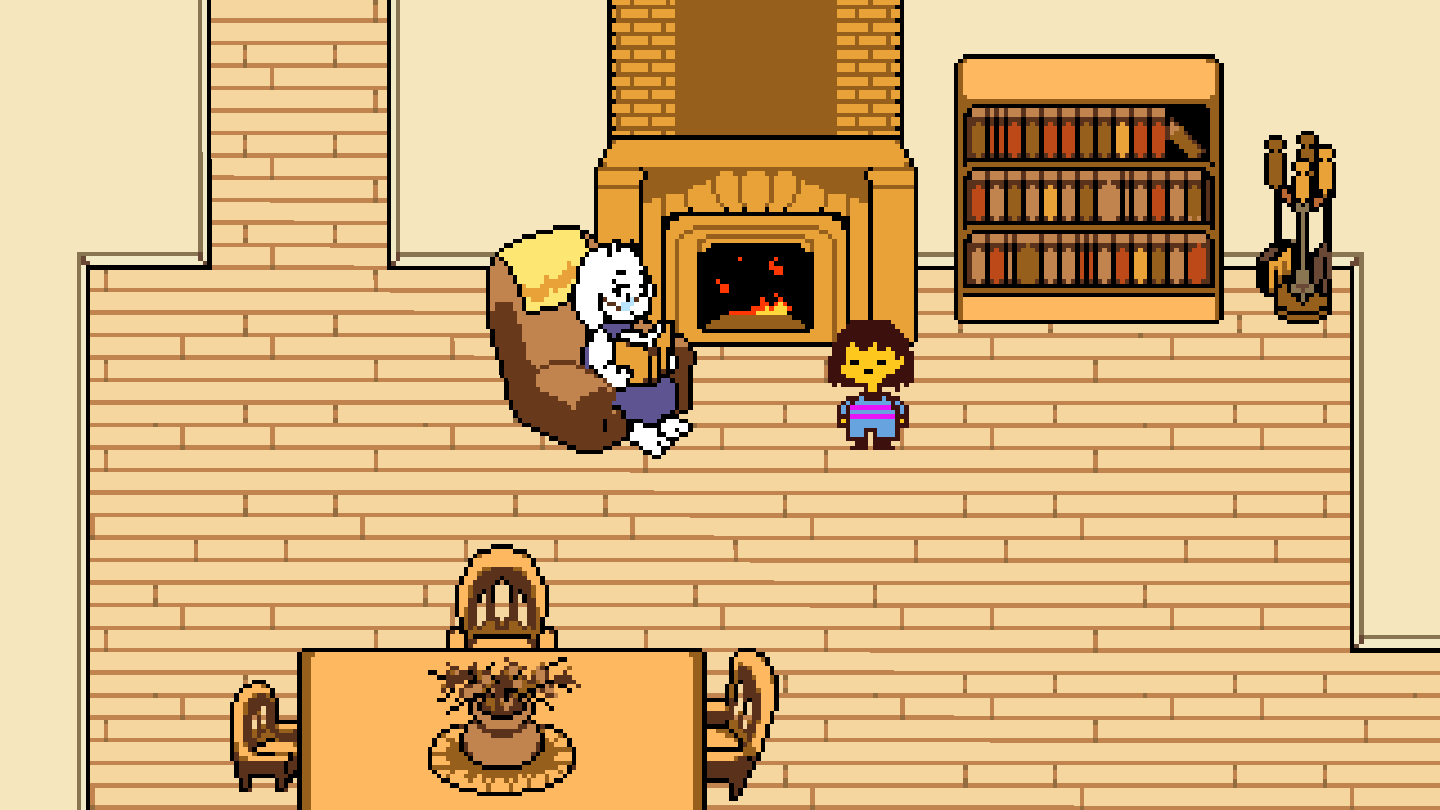

At the time, Fox had precious little game-development experience, though he was familiar with RPG Maker, having built Earthbound ROM hacks during his time at high school. It’s impossible not to see some of Shigesato Itoi’s SNES adventure in Undertale, though Fox says the game is so close to his heart that it’s hard for him to determine which elements of his game were or weren’t inspired by it. “I can definitely say that I wanted to make something that had as much emotional power, humour and wonder as the Mother games, while not necessarily taking the same paths to achieve it,” he says. “Also, the main character is a kid wearing a striped shirt... that’s probably too obvious.”

Either way, the impact it had upon him at an impressionable age is clear. “I played Earthbound when I was four,” he says. “I was so young that it helped me learn to read, and also transformed my brain forever.” Seven years on, his affection would blossom into obsession when he started visiting noted Earthbound fansite starmen.net.

“I became really enamoured with that site, its personality and its denizens, and decided to try to create things to impress the people on it,” he recalls. “Now my friends from that site run Fangamer, which sells my merchandise. So Earthbound and its fandom have never left me.”

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

While Earthbound is Undertale’s most overt influence, in places Fox was keen to deviate from its ideas. Toriel, a kindly, goat-like monster, was a direct reaction to the absence or diminishment of mother characters in RPGs, including Itoi’s game and the Pokémon series. She also served to mock the aggressive tutorials found in many contemporary games; Fox parodied their handholding approach in one sequence by having her physically guide you through a hazardous maze of spikes.

Toriel was just one of the many characters for which Fox sketched out ideas in his college notebook, with many deviating significantly from their final versions. Fox gave each of the central cast their own musical theme, too – and in the case of skeleton brothers Sans and Papyrus, composed the music beforehand. Fan-favourite Megalovania had been originally written for Fox’s 2009 Halloween Hack of Earthbound, back when he was known by his online handle Radiation, and Bonetrousle was initially designed for another RPG Fox had been working on that was ultimately never released. The latter in particular fits the character of Papyrus so well it’s hard to imagine it elsewhere. We ask Fox if the music informed the characterisation, or if he wrote the characters and then decided which themes should be used. “I’m not sure,” he replies. “It probably helped set the mood of the scenes they’re in, but as for Papyrus’s personality, it existed before I decided I would use that song. Most of the other themes were written specifically for the characters.”

Having established such a memorable cast, it seemed a shame to have the player kill them off. Fox conceived the idea of being able to spare the monsters you battle before writing the story, though in practice the Pacifist route takes more effort than the Neutral one, making it more difficult to stick to your principles. “In games, I noticed that the ‘good path’ was sometimes the easiest one,” Fox says. “But if you do things without effort, then it doesn’t feel meaningful.” The Genocide route is harder still, though not simply because of one particularly difficult battle: killing characters that you’ve grown fond of is inherently more challenging than dodging hails of projectiles. For Fox, the biggest problem was one specific encounter. “I had trouble designing Mettaton’s battle,” he admits. “Coming up with gameplay ideas is difficult for me.”

Still, he had plenty of them by the time he took to Kickstarter in June 2013 to fund further development of the game. Fox had already built a demo that backers could download from the campaign page, and his ambitions for Undertale had grown considerably, though he rebuts the suggestion that it was ever intended to be a short game. “I was just unsure if it was humanly possible to create it before making the demo,” he says. “The reason it was bigger than expected is because my expectations of the areas, battles and so on increased a lot after making the demo.” Fox asked for a slender $5,000, and ended up with ten times as much. His estimate of a summer 2014 release proved optimistic, with the finished game eventually launching in September 2015, though by crowdfunding standards that’s neither uncommon nor excessive.

Besides, the response that greeted Undertale proved that Fox had used the extra time extremely well. Though it gained some very positive reviews, his game was more of a word-of-mouth success, picking up momentum as players excitedly discussed and debated its characters, its mysteries and the fearsome difficulty of its most challenging boss fights. Within three months, Undertale had become one of the year’s biggest sellers on Steam, shifting half a million copies. Two months into the new year, that tally had doubled. Elsewhere, its growing online community helped propel it to another unlikely success: in a Best Game Ever poll celebrating the 20th anniversary of the walkthrough website GameFAQs, Undertale beat a range of classics, earning a comfortable victory over The Legend Of Zelda: Ocarina Of Time in the final. Soon, its reach began to extend even further, after Fox approached 8-4 Ltd, the Shibuya-based localisation studio, to discuss bringing Undertale to a Japanese audience. 8-4 suggested porting it to PS4 and Vita, and by August of this year it had gained a new lease of life on console.

Fox, who had only created the game with himself and his friends in mind, was taken aback by its popularity – this was, after all, the most improbable of hits. “It takes influence from many strange sources, the graphics look bad in places, the gameplay is very simple,” he says. “Most of all, the game’s humour and surprise is derived from the fact that it defies the expected conventions of normal RPGs. That’s the most interesting part to me, that even without understanding of the genre’s conventions, the game still resonates with people – kids included. That’s very cool.”

Indeed, the game seemed to find particular favour with younger players. Fox attributes the awareness of Undertale among that group to the number of Let’s Players who picked up on the game and released playthroughs on YouTube.

If its virality ensured the attention of young eyes, there were other reasons why youngsters were so enamoured with the game. “It’s funny, it’s messed up, kind of scary, and isn’t for kids, but doesn’t exclude them,” he says. “Kids love messed-up stuff that isn’t for kids, but doesn’t exclude them.”

“I played Earthbound when I was four years old. It transformed my brain forever”

Toby Fox

For Fox, meanwhile, success has been something of a double-edged sword. It’s not wholly accurate to say he’s retreated from public view, though he’s a cautious interviewee, his newfound celebrity giving him good reason to be careful about what he says. But that’s fitting for the creator of a game that bears all the hallmarks of outsider art, its willingness to boldly flout genre traditions making its breakout status seem even more unlikely. You could even say Fox’s modus operandi hasn’t changed much since then. Undertale feels not unlike a ROM hack; it’s charged with the punkish energy and infectious passion you’d associate with a fan-made add-on, its rough edges contributing to its charm. In a reflective blog post on its first anniversary, Fox self-deprecatingly described it as “an 8/10, niche RPG game”. Though when we ask if there’s anything he would have done differently, he expresses only one regret. During development, he’d grown concerned that the Muffet miniboss fight was too difficult, and tweaked it a number of times – but he wishes he’d made it even easier.

Most of us would struggle to deal with the sudden rush of attention Undertale brought its creator, and it’s evident that Fox hasn’t been entirely comfortable in the glare of the spotlight. Two years on from its PC launch, has he been able to make his peace with the game’s popularity? “The phrase ‘make peace’ sounds kind of harsh,” he says. “I’ve always been glad many people have been able to enjoy playing the game, especially that it’s given kids something to be excited about. However, my life has changed permanently and will never change back.”

If there’s a hint of ruefulness in those words, it’s easy to understand why. Fox can never make another Undertale, or at least something with quite the same maverick spirit. He and his game are too well-known for any new material to be considered purely on its own terms, or to come from nowhere and surprise everyone in the same way his debut did. But just as Earthbound inspired him, perhaps Undertale might motivate another budding Toby Fox to create something similarly strange and wonderful. “I hope someday a kid who liked Undertale grows up and makes an amazing game,” he says. “I would be happy to play that.” Now, that would be interesting.