One indie dev's solution to overcrowding on Steam: Make games that are 'infinite content generators'

Jason Rohrer analyzes Steam's biggest indie successes and finds they generate endless "unique situations."

"We used to say 'make the kinds of games we want to play," indie designer Jason Rohrer said in his Game Developers Conference panel, Before and After the Indie Apocalypse, on Monday. "Now we need to make the kinds of games we actually do play. Our own personal play histories don't lie."

In Rohrer’s case, that game was Rust, a survival sim he’s played for some 300 hours over the years. Throughout his talk Rohrer addressed the idea that an indiepocalypse has struck Steam in the past several years, as the massive increase in releases has sapped money and attention from games that would’ve once been big successes for small indie teams. His opinion, after looking at how his own latest game sold and what’s succeeding on Steam? There was no indie apocalypse.

“I'd say that the indie apocalypse, in general as a concept, isn't real, but something has changed," he said. "I think that maybe what we had was more of a consumable game apocalypse, which doesn't really roll off the tongue.” Rohrer's advice to devs is to make more of the kinds of games they tend to play in their free time: "lifestyle" or "hobby" games that are fun for months or years on end.

“Consumable games” mean the shorter, narrative-focused games often associated with indie devs. Games like Tacoma and What Remains of Edith Finch, which don’t have the replayability of more systems-driven or sandbox games. Rohrer based his argument on how many players these games currently had on Steam, compared to monster indie successes like Subnautica and a handful of indie games the audience had never heard of before. Feed and Grow: Fish, Airport CEO, and Staxel were examples of games that no one is talking about, but have hundreds of concurrent players on Steam. They're underground successes.

"There are more than 1000 games on Steam at this very moment with more concurrent players than One Hour One Life," Rohrer said. "There are tons and tons and tons of huge success stories here. Life-changing financial results for lots of game developers. We're just not hearing about them."

Rohrer also looked at how many YouTube videos various games had wracked up, pointing out the obvious challenge of spreading word of mouth for shorter narrative games: Most people interested in those games simply won’t watch a video, because they don’t want to spoil the story. And systemic games are much more fertile ground for multiple videos, because they’re never the same twice.

Without hard sales data, the talk hinged on concurrent players as a barometer of success, and that’s obviously an imperfect metric. Of course narrative games from a year or three ago are going to have far fewer active players on Steam today than a game like Subnautica; shorter play sessions mean fewer concurrent players at any given time. Those games could still be successful. It’s just hard to tell without the numbers.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

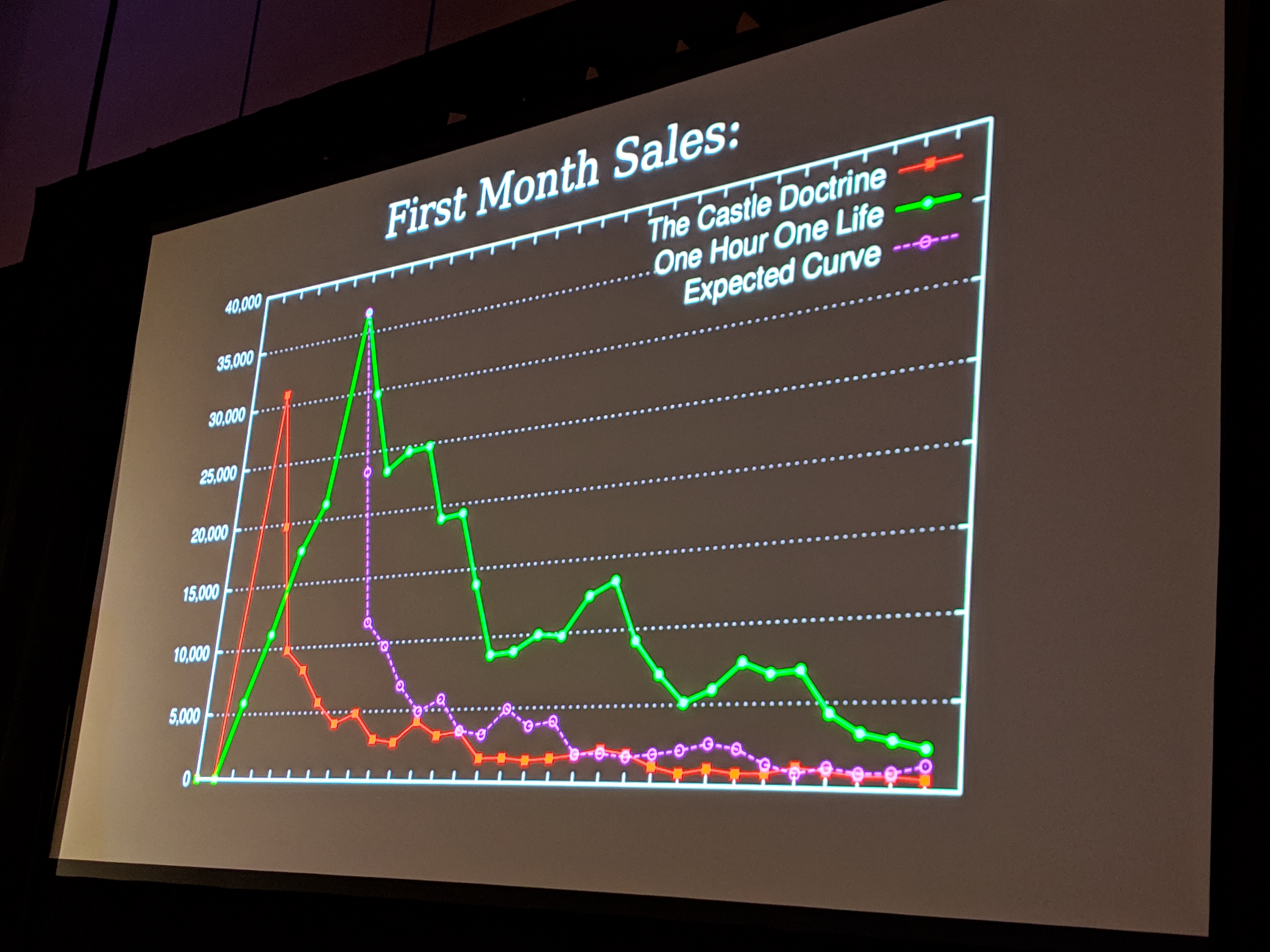

But he makes a good argument that the big bucks on Steam today come from games with sustained interest and word of mouth. His game One Hour One Life had poor sales on launch day, typically the biggest sales day for a new game--a "dismal" 315 sales, compared to 2400 sales for his previous game, The Castle Doctrine. He pointed to far fewer reviews and articles, but a major difference was the lack of a front page debut. In the past Valve gave Rohrer a front-page slot on launch day. Today, front page exposure is driven by algorithms.

That's now a common problem, as so many games come out on Steam every day compared to just a few years ago. But the key, at least for One Hour One Life, is that continued bubbling interest kept sales going until Steam’s algorithms pushed it to the front page days after launch, and it’s had many more sales spikes in the four months since.

The striking thing about this talk to me is that Rohrer's advice for indie developers mirrors the same path triple-A game development has taken this generation with games as a service, even if the substance of those games is dramatically different. You wouldn't immediately look at One Hour One Life and The Division 2 and think of them as having much in common, and "indie" as a term still often conjures roguelikes with pixel art or narrative adventure games. Rohrer's argument is that when those games are big successes on Steam, it's now the outlier; the likely path to success is in games that keep people playing, making videos, and spreading word of mouth.

"My take home message: if you want to reduce your risk in this modern ecosystem, it's pretty simple. Make unique situation generators," Rohrer said. "It's kind of an interesting piece of advice to be giving, because even if the indie apocalypse hadn't happened, I might still be giving people that advice, in general. In my opinion, they seem like the most interesting kinds of games to be making, anyway."

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).