Meet the game makers determined to stop development from ruining lives

The devs behind The Long Dark, Minit, John Wick Hex, and more, talk about tackling crunch and overwork.

This article first appeared in PC Gamer magazine issue 357 in May 2021. Every month we run exclusive features exploring the world of PC gaming—from behind-the-scenes previews, to incredible community stories, to fascinating interviews, and more.

The games industry never stood a chance. Raphael van Lierop, who served as narrative director on Far Cry 3, believes the medium inherited crunch from its parent industries—the expectation of overwork baked into software and filmmaking long before a programmer first managed to steer a pixel across a screen. By the time van Lierop joined a game studio in the early 2000s, burnout was considered best practice.

"We didn't at all associate these things with poor management or poor planning practices," van Lierop says. "We believed crunch was a necessary prerequisite to creating something exceptional."

It was only after a dozen years of 70 to 80 hour weeks, as van Lierop found himself putting his kids to bed only to turn around and drive back to the office, that he recognised an unhealthy spiral. "I recall a night in particular during a really heavy crunch period, my wife looking over my shoulder and reflecting that she didn't understand why I was making so many personal sacrifices for something that didn't feel that much like 'me,'" he says. "I realised I'd never stopped to ask myself if this was something I'd wanted. Shortly after that game shipped I decided that I would never go back to another AAA studio, and Hinterland was largely born from that decision."

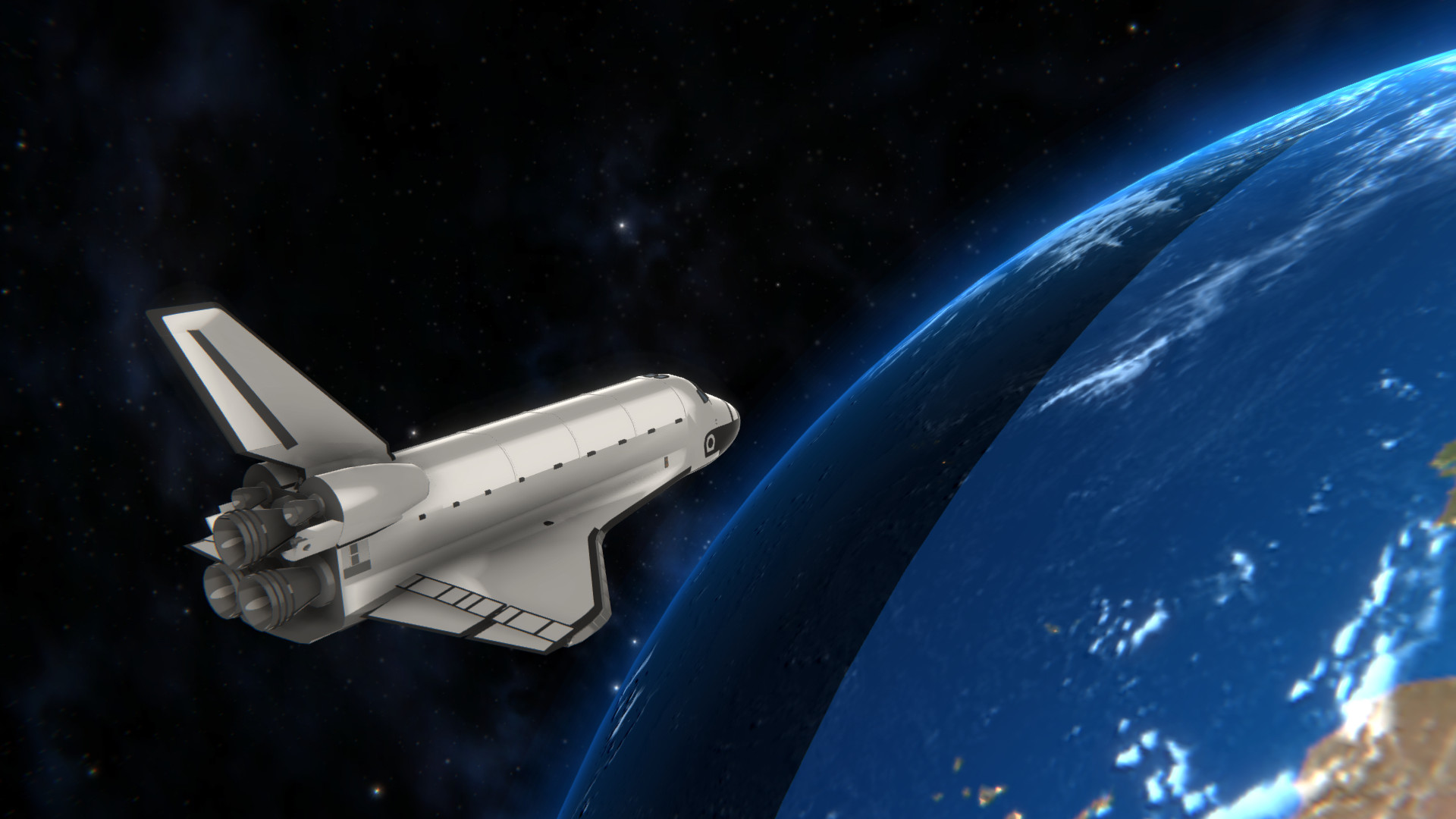

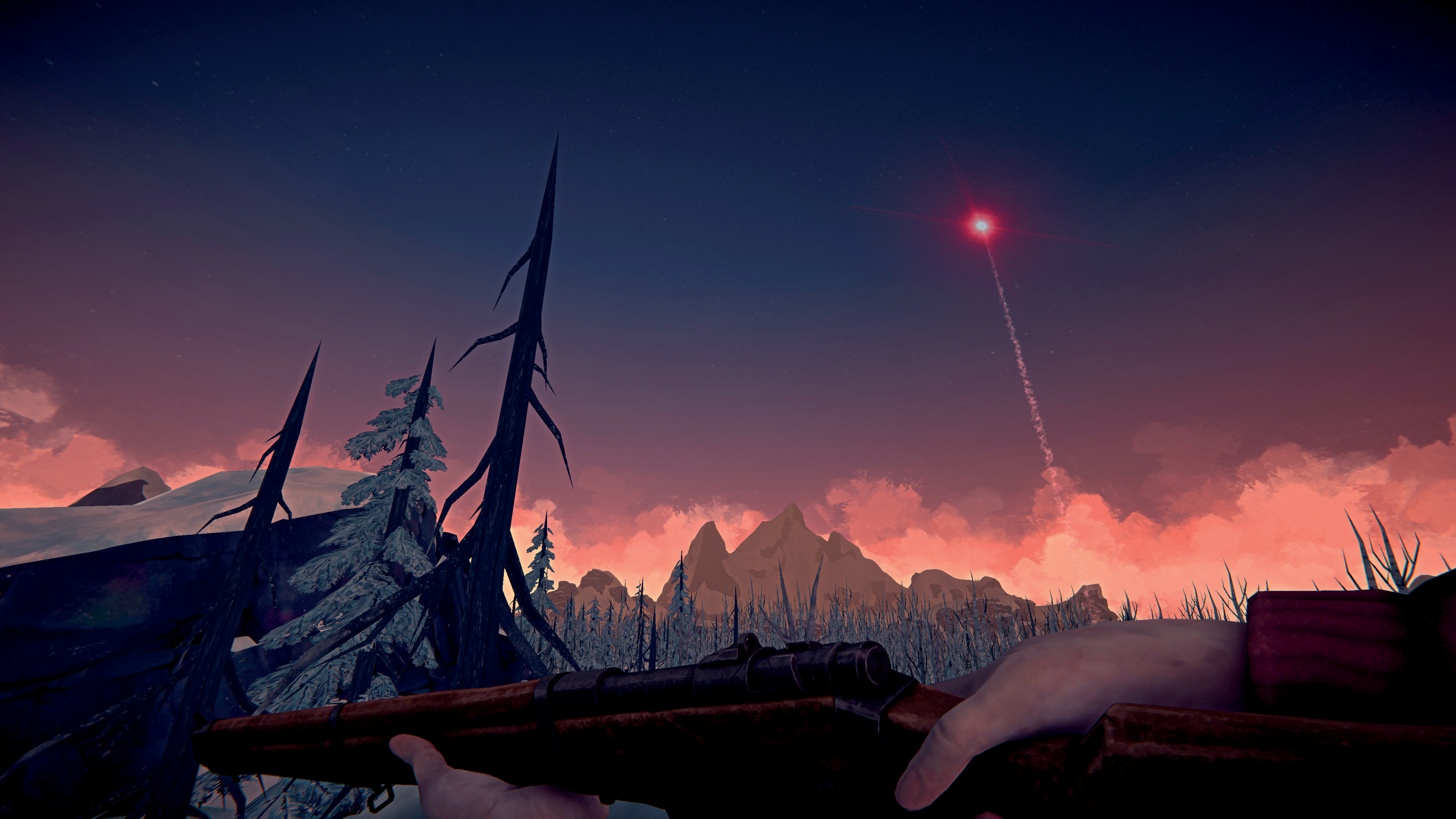

Hinterland, which develops top-rated Steam survival game The Long Dark, is part of a new wave of studios dedicated to ending crunch. Though divided by continents, cultures and genres, they face shared problems—and offer a glimmer of hope that the rest of the industry can one day find similar solutions.

Bad romance

Overwork is not exclusive to AAA studios. Famously, Stardew Valley developer Eric Barone spent four years in self-imposed crunch—averaging ten hours a day, seven days a week. "We still really romanticise the solo dev working in their basement for years who shipped a huge hit," van Lierop says. "The games press plays a big role in this. The issue is that for every single indie hit that was made under those extreme conditions, 100 or 1,000 failed miserably and those developers ruined their health, their finances, and their relationships chasing a false dream."

For Vlambeer, the two-man team behind Nuclear Throne and Luftrausers, the dream was realised—but designer Jan Willem Nijman nonetheless regrets the damage done during the process.

"I burnt out a few times," he says. "The launch of Nuclear Throne was a major one. Recovery means not working for an extended period of time, being a barely functioning human, and then many months, if not years, to slowly get back to normal. On top of that, I lost some of my 'elasticity'—I can't push myself remotely as far anymore without quickly burning out again."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

More recently, during the development of Minit and Disc Room—two critically-acclaimed games Nijman made with a variety of collaborators for Devolver Digital—he took care to prioritise life over work. "If it needs more time, it needs more time," he says. "If it means that the game needs to be a bit smaller, that's also fine. For us, making things leisurely is just as fast as making them under stress. In fact, I am convinced that by living a fuller life you can be more creative and are more open to inspiration."

Auroch and a hard place

But what happens when the scope and timeline of your game is decided by an outside force, like a publisher? It's often midsized studios that are trapped in the vice—accepting high-pressure projects in order to make payroll. Auroch Digital, which now makes the space agency strategy game Mars Horizon, spent several years bouncing between tabletop-related games like Chainsaw Warrior, Ogre and Achtung! Cthulhu Tactics. In its early days, developers weren't consulted when deals were made.

The team would have a contract put in front of them saying 'We're making this game in 12 months, for this much money.

Nina Collins

"The first two projects that I worked on were disasters, from a production point of view," partnership and production manager Nina Collins explains to me. "The team would have a contract put in front of them saying 'We're making this game in 12 months, for this much money'. Both of those projects were very much firefighting, and that's what led to them having crunch—we had overpromised on quality, on scope, and we didn't have enough time or budget. That was when, as a company, we said 'This isn't sustainable.'"

In the years that followed, Auroch started tracking the time staffers spent on tasks, in and out of normal working hours. "What you get with that data is the hidden work," creative producer Peter Willington says. "And if you can't track the hidden work, how in the hell can you make good estimates for future projects? Production is something that happens before you've signed the contract."

Beyond making more sensible promises to publishers, Auroch now schedules its weeks differently too—planning work for only four days out of five, leaving extra time for meetings. "You try and pull developers who are under pressure and crunching into a discussion," Collins says. "Their stress levels go to the max. And the problem is that they don't view meetings as part of development. And in that meeting, as a group, you might find out that you can cut 20 days off the AI."

Willington knew these measures were working when, on launch day for Dark Future: Blood Red States, the team was finished coding by lunchtime—early enough to pass around a bottle of whisky. "I was very emotional about that," he says. "That was the pivot point."

Late night chat

Beating crunch takes soft skills as well as spreadsheets, however. As soon as Mike Bithell made enough money to start employing people, he pledged that they wouldn't crunch. But sticking to that principle has meant actively catching staff in the act of working too hard.

"Still to this day, I have to check if they're working late," the John Wick Hex director told me at Yorkshire Games Festival last year. "They've worked in environments where that's expected of them, or often they just really love their job. They'll think that's the way to get into my good books to get a promotion or a pay rise. It's my job as a boss to keep reminding people that it's not how they impress me."

Auroch has encountered the same problem. "No matter how many times we tell people that we are anti-crunch, when they're first starting a new job, people still feel like they're trying to prove themselves," Collins says. "It's proving themselves in the wrong way—because there's historic stuff from the industry. And it's really important to stop people doing that, because they're going to run themselves into the ground doing something that's completely unnecessary."

Traditionally, many game studios have presented crunch as optional—but the consequences of opting out have been severe. "It was never explicitly stated, but I think everyone knew that the 'nine to fivers' were not the ones that would get the good promotions, because they couldn't possibly be that dedicated or ambitious," van Lierop says. "What I want to hear from studio leaders is, they never have to talk to their staff about work-life balance or having healthy work habits because they all know it's expected of them. At Hinterland, if we have to remind team members not to work too hard, it's a failure of our leadership." Nijman believes it's important to lead by doing. "If you're the boss who's working late hours, you're just overburdening yourself and setting an unhealthy example."

Boss fight

It's this last point that has proven tricky to put into practice at some of the studios I've spoken to. Somewhat hypocritically, Bithell still works overtime, a fact his staff have called him out on. "We had a postmortem after we released John Wick, and the biggest piece of feedback from my entire team was 'Mike works too hard,'" he says. It's an issue Bithell Games is addressing by bringing in extra producers.

We may never get my hours down fully, but that's OK because I get to own the company. I get my name on the fucking front of the game. It's a very different thing when you're an employee, being paid hourly, and I can't ask for the same degree of devotion

Mike Bithell

"That's one of our objectives as a company," he says. "We may never get my hours down fully, but that's OK because I get to own the company. I get my name on the fucking front of the game. It's a very different thing when you're an employee, being paid hourly, and I can't ask for the same degree of devotion."

Auroch's last two games involved no crunch at all, but some senior staff do still put in the extra time. "We've had someone start that will hopefully spread that out," Collins says. "There's always more to be done, but we can proudly say we do not do crunch."

At Hinterland, members of the team have crunched on three occasions: once to get The Long Dark through Xbox certification before reveal at E3; once to fix PS4 technical issues before the game hit 1.0; and once to get overhauled story episodes out before Christmas of 2018.

"It's no coincidence that these three instances all occurred around fixed external milestones," van Lierop says. "Timing commitments we'd made to our partners or our players that we felt we couldn't break. Our solution since has been to avoid making public commitments like that, and as much as possible to avoid lining up significant launches of new content with new platforms."

Quality of life

It's notable that The Long Dark, Mars Horizon, Minit, and Disc Room are all reviewed as 'Very Positive' on Steam—the highest honour in the field of player satisfaction. Developers may worry that forgoing crunch will lead to unfinished games, disappointed critics, or frustrated fans waiting for updates. But all of the developers interviewed for this article believe their games have turned out better since turning their backs on overwork.

"The first game I worked on [at Auroch] turned out fine, but no one was like 'This is great,'" Willington says. "We're making our best looking, best playing games since we stopped doing this stuff."

"Even if you're a cynic, crunch is a bad idea," Bithell says. "All the data we have on it says it demolishes someone's ability to produce work. It's really just common sense. You have to understand what the biological limitations of being a human being are. You can't work crazy hours, and the research all backs up that position."

"It's generally understood that work done under extended crunch conditions is often not good or high-quality work," van Lierop explains. "Why would you want that? You're burning your people out to get worse results and eventually lose them, which just puts more burden on the next batch. I don't think the results are compromised by avoiding crunch. I think they are definitely compromised by depending on crunch to get your games out the door."

Black diamonds

The question, then, isn't whether avoiding crunch works. It's whether the rest of the industry will follow suit. Bithell's established reputation allows him to stand up for his team in publisher negotiations, while Auroch's cashflow means it can afford to delay milestones—both privileges that a new indie team may not have at their disposal.

Larger developers, meanwhile, have less incentive to end crunch. "They can pull in another coder that's just as good," Collins says. "We couldn't afford to lose those people, so we had to sort it out." What's more, AAA studios are often beholden to shareholders—who can be much less understanding than players. "Hitting quarterly revenue targets becomes the measure of business health, versus the health of the teams or the quality of the products," van Lierop says.

But, as we've seen before, players can influence whether or not developers ruin their health and home lives, even at the highest levels—by voting with their wallets. "What we need in games is more of a 'blood diamonds' concept—societal pressure that acknowledges the human cost of a product should be part of how we measure its value," van Lierop says. "Until consumer sentiment changes and people stop buying games made under unhealthy working conditions, nothing will fundamentally change around crunch."

"Even if it would make no difference for the final product, the fact that it makes people unhappy, unhealthy, and takes so much time off their lives is more than enough reason to end the whole practice once and for all," Nijman says. "Instead of saying 'Not destroying the Amazon Rainforest is good for the economy,' people need to realise that we shouldn't be destroying the Amazon anyway."

Play Minit today, and you'll find it filled with places and people the team encountered while out living their lives, not staring into a monitor. "Spending time not working is important to fuel that," Nijman explains. "There's a quote floating around somewhere that there are two types of poets: those who try, try, try and squeeze and eventually get their words on the page, and those who live life and sometimes poetry happens. I want to keep designing games like that second group of poets."

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.