How developers create cinematics

Making a scene.

You might assume that cutscenes are a simple piece of game development, without all that pesky interaction. this is not the case. in fact, examining the production process for cutscenes reveals a messy truth underlying most games—the inherent risk accompanying their nonlinear development.

“For us, the cutscenes were written months before the gameplay was finalised, so we were writing these cinematic beats of high tension and emotional fulfillment... when all the lead-up to those moments hadn’t even been conceptualised yet,” says Dead Rising 4 writer Shannon Campbell. “We had a map and we knew the rough destinations we wanted to hit, but the road we’d take to get there was a complete mystery.”

This process is not atypical, as corroborated by Assassin’s Creed III and Far Cry 4 creative director Alex Hutchison. “Usually you want to lock the script as late as possible,” he says, “so it can respond to changes in design and missions effectively. But you need a draft script and a strong sense of the narrative early so you can make sure everything will fit together.”

In large projects, due to the need to integrate elements from actor performances to the latest rendering tech, once a cutscene is built, changes range from expensive to impossible. “Every change costs more the later in the process you ask for it,” says Hutchison. “Changing a whole story on day one costs nothing because you’ve invested nothing, but changing something in the last month is not only very expensive, it’s probably impossible unless it’s a straight cut.” Campbell calls out performance capture as an example of flexibility restricting as time goes on. “Depending on how much money and production time you’re dropping on cutscenes, once a scene is performed and captured, there’s not much editing you can do to the actual physical performance.”

While cutscenes are being written and conceived, it falls to artists like Alex Kanaris-Sotiriou to begin seeing whether they’ll even work. “The concepting stage for cutscenes generally begins early in a project once the core gameplay and broad narrative/event arc have been established,” Kanaris-Sotiriou says. “Most productions will want their cutscenes blocked out in some form for alpha (where the game is playable from start to finish using placeholder assets). The cutscenes at this point may be video animatics (moving storyboards) or implemented in a crude fashion with rough camera shots, sliding ‘T-pose’ characters and placeholder robo-dialogue.” Previsualisation, or ‘previs’, fits neatly into this process, combining 2D and 3D assets to block out scenes before the resources are dedicated to fully realise them.

As development accelerates, designers have to get crafty—particularly in cases where cutscenes are shown in-engine. James Henley, a former cinematic designer at BioWare, reveals some shortcuts necessary to get the sheer amount of dramatic content needed into Jade Empire, Dragon Age: Origins, and Mass Effect: “Working with pre-existing animations, we often altered blend weights on animations or used small parts of a longer animation that may imply an entirely different action when viewed out of context. … Non-standard movement was often implied by cobbling starts and ends of other animations together and carefully managing camera motion and cuts to imply action.”

Salarian cinema

Once a cutscene is produced, it falls to people like Michael Elliot—a former content QA tester on Mass Effect 3—to ensure everything runs smoothly. Sometimes, this requires viewing the same scene multiple times. One day, this culminated in an attempt to track an issue with the final confession of Mordin Solus. “There is a moment, near the end of the scene,” Elliot recounts, “where Mordin cuts off Shepard mid-argument and yells, ‘I made a mistake!” Then there’s a beat where Mordin calms himself and says again, “I made a mistake.’ ... During one of my playthroughs when I was testing the scene my PC hitched and Mordin’s beat between the two lines was missing. Without it that pivotal moment felt wrong, it felt rushed, you don’t get to see Mordin came to terms with what he is saying.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

“Seeing how [those] few seconds of silence made all the difference in that scene made me realise how much attention went into creating the game, and how much I enjoyed what I was doing.”

That’s what all of this work from all of these people ultimately hopes to achieve. A two-second pause that, for the player, will mean everything.

Developer favourites

Alex Kanaris-Sotiriou, Polygon Treehouse

Kanaris-Sotiriou appreciates how the Governor’s Mansion brawl in the Secret of Monkey Island uses sound effects and Batman-like captions to capture the player’s imagination.

Jake Rodkin, Valve

Rodkin recalls how the opening of Full Throttle straddled the technology gap facing adventure games with confidence, mixing pixel characters with 3D motorcycles and cars.

Sean Oxspring

Oxspring reflects on the shocking fall of Prince Arthas in Warcraft III, depicted in the purging of Stratholme.“I remember being like, ‘I understand why but jeez there’s got to be a better way?’”

Chella Ramanan, 3-Fold Games

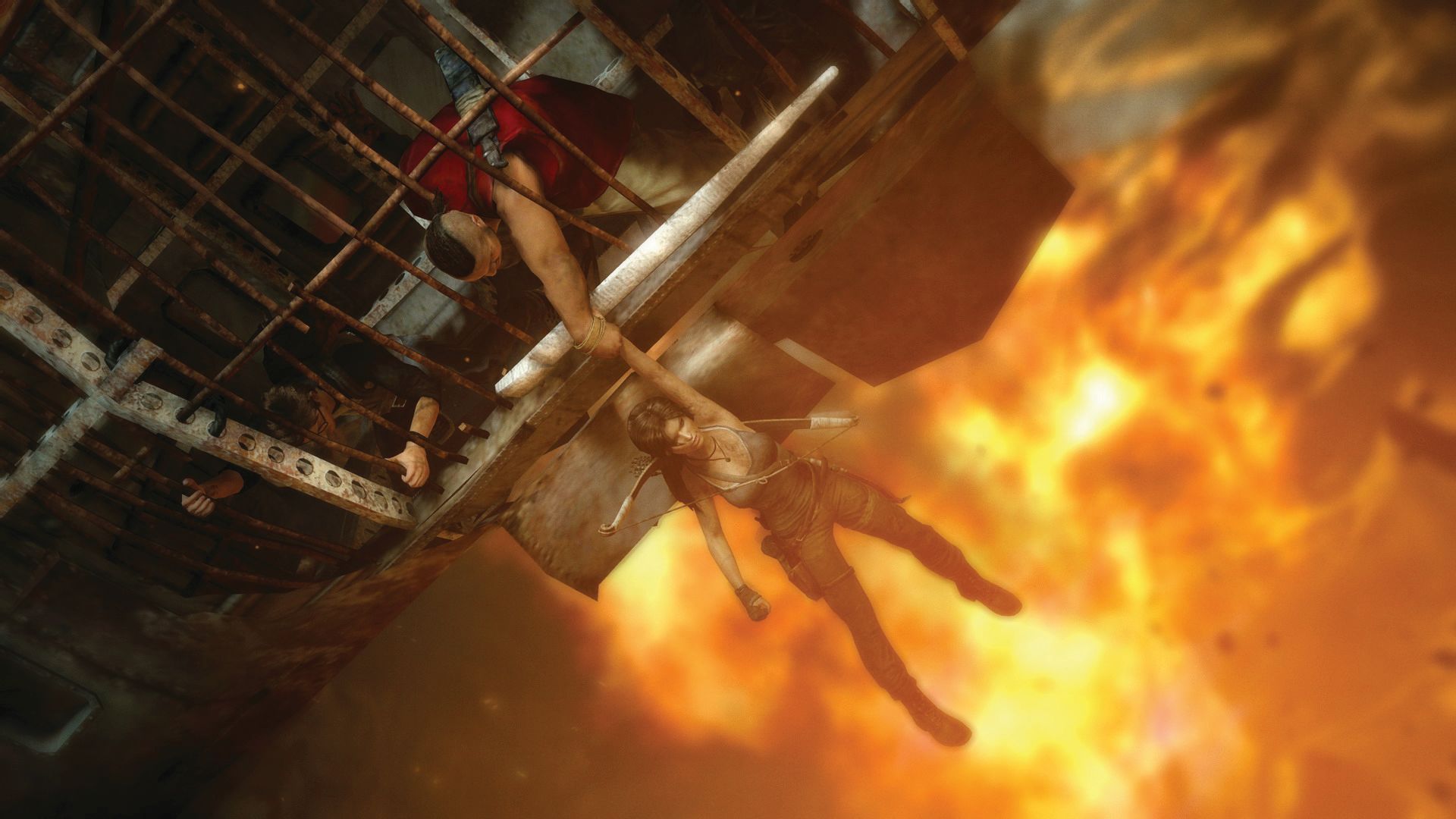

Ramanan spotlighted a scene of Aya jumping into Bayek’s arms in Assassin’s Creed Origins, noting the rarity of people of colour being depicted as sexy, strong, intelligent and in love.