This new Counter-Strike map was created to smuggle the truth about the Ukraine war into Russia

The Finnish newspaper Helsinin Sanomat has created a CS:GO map with a secret press room detailing the war in Ukraine.

The newspaper Helsingin Sanomat has sometimes been described as a cultural institution in Finland, the country's own paper of record and over the years a campaigning media presence. Ever since Russia's illegal invasion of Ukraine, Helsingin Sanomat's coverage has been extensive and extensively critical of the Putin regime, to the extent of setting up a dedicated website (banned in Russia, naturally). Now it's found a new avenue of expression: a Counter-Strike map.

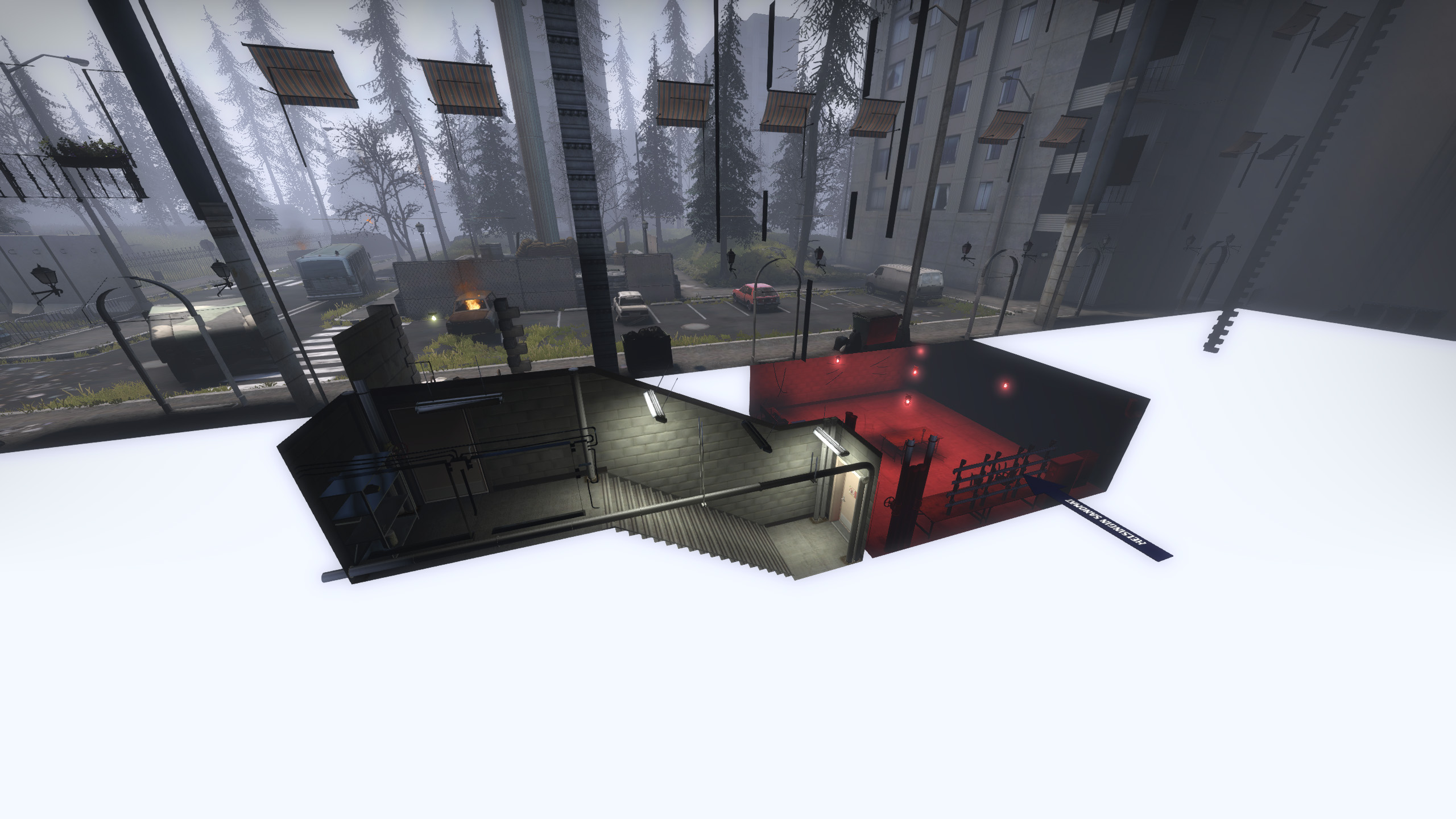

To coincide with World Press Freedom Day, Helsingin Sanomat has commissioned the creation of a Counter-Strike: Global Offensive map that resembles a war-torn Ukrainian city, but also hides a secret. The map includes a corridor that leads to an underground bunker, within which is a variety of information and news coverage (in English and Russian) relating to Russia's actions in Ukraine. The map is named de_voyna: The word "voyna" means war in Russian, and over there it's forbidden to use this word to describe the war in Ukraine.

The information within the secret room comes from Helsingin Sanomat's war correspondents in Ukraine, and the newspaper's editor-in-chief Antero Mukka says the idea came about because "Russians have very little chance to receive independent information about Putin’s invasion of Ukraine" but "the gaming world and gamers themselves are still left unchecked."

It is most certainly true that the Russian state tightly controls the media diet fed to its population, though whether hiding a secret newspaper in what Mukka calls "the world's most popular war game" is an effective way of breaching that remains to be seen. Mukka says the key is that the Russian administration doesn't associate games with journalistic content and so, although it's targeted independent media and foreign outlets like the BBC, it hasn't stopped Russians from accessing Counter-Strike servers.

"As the Russian government has de facto suppressed its national press and blocked access to foreign media," said Mukka, "Counter-Strike has remained as one of the rare channels that allows us to communicate independent information to Russians about real events from the war."

Images and text in the map's secret room detail specific incidents and atrocities and statistics about the war including, per Helsingin Sanomat, "civilian casualties, human suffering, the mass murders committed by Russian troops and the amount of lives lost on the front." All the information is in both English and Russian.

"Ordinary Russians know practically nothing about the war crimes and atrocities toward civilians committed by the Russian army," said Mukka. "One of the most touching stories in the secret room is about a Ukrainian man that went to the store. While he was there, Russian troops killed his family with a missile strike. The secret room built into the game is meant to force Russian gamers to face what's really going on in the war in Ukraine."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

While this map contains serious journalism, there is an element of the PR stunt to the whole thing, not least in the slight wooliness Helsingin Sonomat seems to have about exactly how Counter-Strike servers work and how players will access this. It also seems inevitable that, should it acquire any traction, the Putin regime will notice and do what it does in terms of trying to limit Russian players' access.

However, that is also the nature of journalism in a time of war: Propagandistic methods may be the only way to reach certain people with legitimate information, and the fact no one really knows how many Russians this will reach cuts both ways. It's not as if, back in the days of dropping leaflets from the skies, there was ever any way of knowing how many people read them: Just that some would.

And Helsingin Sonomat is as serious about the map's content as it gets. The room contains graphic descriptions of incidents in the war from on-the-ground reporters. "Helsingin Sanomat’s reporter Petteri Tuohinen and photographer Kalle Koponen were in Bucha, north of Kyiv, when the cruelties of the Russian army were starting to come to light," reads the newspaper's own report on the project (contains graphic war photography). "The massacre was not fake news. It all happened..."

According to the paper, the Russian defence ministry through Russian state media instead circulated reports that the Ukrainian army was responsible for these atrocities in Bucha, and that all the Russian army had done was try to help the population.

The room contains accounts of the massacre in Bucha, where the Ukrainian government says at least 458 people died (though the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights estimates 73-128 people died). It also details the awful story of Yuriy Glodan in Odessa, whose entire family including his three month-old daughter were killed by a cruise missile while he was food shopping. Finally it contains Helsingin Sanomat's best attempt to catalogue the number of Russians who have died in this war, which it currently estimates at 70,000.

The map was created by two Counter-Strike map designers who understandably wish to remain anonymous. However they did issue a joint statement about the work, emphasising their pride at being "involved in making such a map with a humanitarian purpose connected to the real world.”

The statement ends: “Russia's senseless aggression on Ukraine has killed tens of thousands of civilians, including children. The least we can do is to bring Putin’s war crimes and Russian propaganda to light.”

Rich is a games journalist with 15 years' experience, beginning his career on Edge magazine before working for a wide range of outlets, including Ars Technica, Eurogamer, GamesRadar+, Gamespot, the Guardian, IGN, the New Statesman, Polygon, and Vice. He was the editor of Kotaku UK, the UK arm of Kotaku, for three years before joining PC Gamer. He is the author of a Brief History of Video Games, a full history of the medium, which the Midwest Book Review described as "[a] must-read for serious minded game historians and curious video game connoisseurs alike."