The US Air Force has finally stopped using floppy disks in its nuclear weapons system

Welcome to 2019.

Since the 1970s, the United States Air Force has been using the same computer system designed to launch nuclear missiles by order of the President. Of course, such a thing is meant for a crisis situation (feeling those Cold War vibes?), but its SACCS (Strategic Automated Command and Control System) has been reliant on 8-inch floppy disks as a primary storage solution to send emergency messages from nuclear command centers to forces out in the field.

Secure? Sure. Efficient? Maybe not. My gaming PC seems like it would be better suited to the task. But after years of debate, the SACCS is getting a long overdue upgrade to a solid state digital storage solution. As for the IBM Series/1 computer, that seems like it will stick around for a while. The Air Force is seeking a replacement for its current SACCS, but it's unclear how far it's along in that process or what sort of upgrades have actually taken place; the Air Force has only made recent enhancements to enable speed or connectivity apparently, but in 2016 the Government Accountability Office wrote that the Defense Department planned to "to update its data storage solutions, port expansion processors, portable terminals, and desktop terminals by the end of fiscal year 2017."

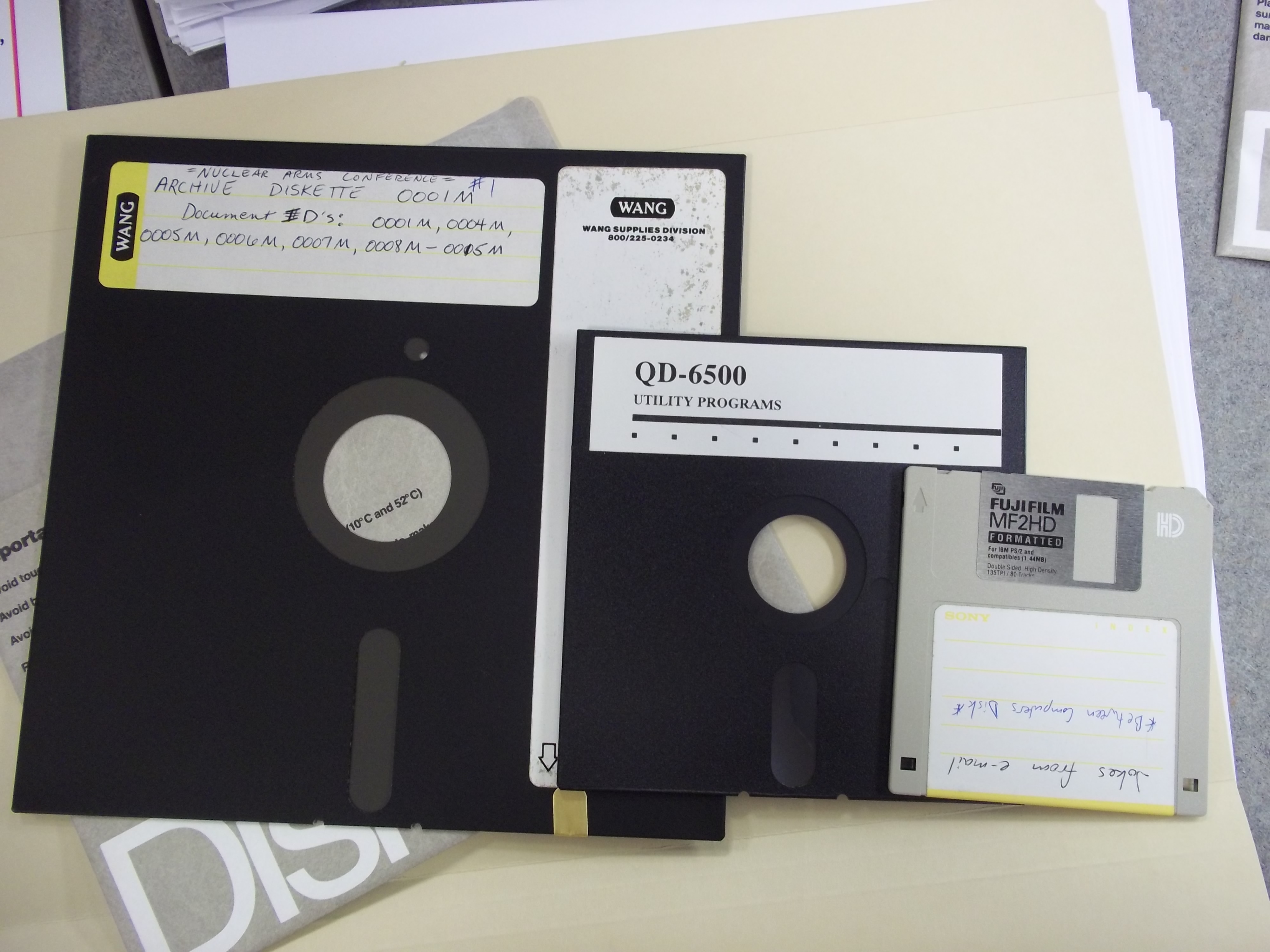

The 8-inch floppy disk (also known as a flexible diskette or memory disk) first became available on the market 1972 and had a whopping 80 kilobytes of data—or 0.000008 gigabytes. The disk itself was a thin, magnetic storage medium encased in a plastic, protective carrier. It was once a universal data format and primary storage mechanism until the the 1990s, when USB 1.0 was created and flash drives replaced floppy disks. But for the time, the 8-inch floppy disk was considered the most cost-effective "high speed, mass storage" device. So, it's kind of crazy to think that the SACCS has been running on a now-ancient system for the last few decades.

However, keeping that IBM Series/1 computer running requires a more specialized set of skills, soldering among them. Because of this, the Air Force prefers to hire civilians who already have the necessary skills needed to maintain and repair the IBM Series/1 computer instead of pulling from their own ranks. Most active-duty Air Force personnel who are trained for computer work are trained to manage modern IT infrastructure.

"You can't hack something that doesn't have an IP address. It's a very unique system—it is old and it is very good," said Lt. Col. Jason Rossi, commander of the Air Force’s 595th Strategic Communications Squadron in an interview with C4ISRNET. Naturally, if someone wanted to hack something as old as the Air Force's SACCS they would most likely need to be physically present at the machine, but that doesn't necessarily mean that any information stored on those 8-inch floppy disks is safe.

A landmark homicide case in the Philippines from 1991 showed as much. A US Air Force serviceman's wife was found murdered, and crucial evidence of the husband's guilt or innocence was on a 5-1/4 inch floppy disk that had been cut up with pinking shears. Investigators literally tapped the disk back together (the thin, flexible magnetic portion) with Scotch tape and were able to put it into a disk drive and get all the information they needed off of it with minimal or no corruption. That case changed the guidelines around data security at the time.

But maybe that case was an anomaly. And of course no one stores information on floppy disks these days—except the Air Force, for now anyway. In any case, welcome to the world of SSDs, Air Force.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Thanks, C4ISRNET.