The history of cyberpunk on PC

For over 30 years, cyberpunk has mapped technology’s most pessimistic path.

Although earlier examples do exist, nothing sums up the mood and aesthetic of cyberpunk quite like the opening of William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer: "The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel." It’s a genre of science fiction often marked by its contrasts; low life and high tech, to quote author Bruce Sterling, and a vision of the near future with its feet heavily planted in both the obsessions and pessimism of the 1980s.

It’s instantly recognisable, and yet defies neat categorisation, with elements of noir, satire, fetishism and paranoia all typically mixed together. In its stock form, it’s the near future as seen from the gutter—individualists struggling to live as they choose in the perpetual darkness and driving rain of oppressive future cities where megacorporations rule everything and everyone. It’s the antithesis of utopian sci-fi such as the Star Trek series, typically rooted in a sense of nihilism and criminality. Corruption is rife, violence is omnipresent, and law belongs to the highest bidder.

However, like most genres, there’s far more to the setting than that. For starters, it’s a dark view of the future that’s also shaped by its creators’ passions; a strong Asian vibe to the worlds, for instance, from the iconic geisha billboard that introduces us to Blade Runner’s near-future Los Angeles, to the existence of archetypes like Shadowrun’s 'street samurai'. The result tends to be worlds that are very cool to visit, but would be hellish to actually live in.

Deeper down though, cyberpunk is a genre that’s less interested in the fancy toys and bright lights as the questions that they raise about humanity—identity, sexuality, ethics, memory, freedom, and more. Blade Runner, for example, is nominally a movie about a cop chasing down robots, but in practice is a deeper philosophical work that explores the nature of humanity by contrasting cold protagonist Deckard with the emotional Replicants he hunts.

This type of exploration is part of most major cyberpunk works of the last few decades, regardless of their origins. Be it the title of Ghost In The Shell referring to a spark of soul even when all organic elements have been replaced with machinery, to The Matrix, widely discussed for both its overt themes, such as the nature of reality, and for the many metaphors that can have read into it, most notably its potential to be seen as a transgender coming out story, and—rather less positively—the rise of philosophies such as 'redpilling' within certain online communities.

Closer to home

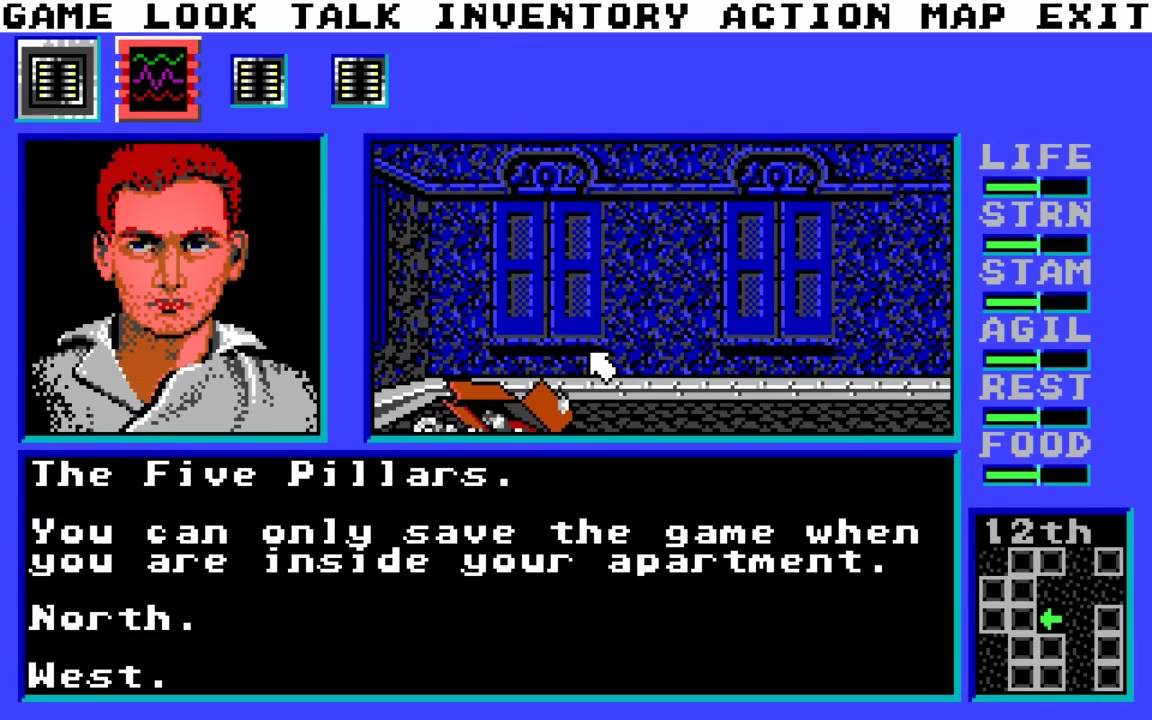

But let’s turn our attention to games. Cyberpunk has been a part of them since the beginning, even if never as popular a setting as you might expect. Neuromancer saw a game conversion as far back as 1988, and many of its elements are still present in cyberspace futures today—hacking as a whole virtual world where the hacker must literally fight against ICE (Intrusion Countermeasure Electronics), upgrades in the form of skill chips, and so on. While not a great game, it was certainly a forward-thinking one, offering adventure/RPG cyberpunk action over a decade before Deus Ex; one where you could go from selling your organs for pocket money, to wandering down the street and finding a religion based on Pong.

As a game though, it made few waves, and this is honestly true for most attempts until the new millennium. Where they’re remembered, it’s primarily for their oddities. The original Blade Runner game particularly stands out here: an 8-bit outing not technically based on the movie—that would have been expensive—but rather 'inspired by the Vangelis soundtrack'. Needless to say, that inspiration somehow led to you being a cop in a big coat chasing down 'replidroids' in a futuristic city. That was 1985. Westwood’s official game wouldn’t arrive until 1997.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Not being huge commercial successes didn’t mean that these games weren’t interesting. One of the more ambitious ones was Westwood’s Circuit’s Edge—that’s Westwood as in the future creator of Command & Conquer. This was a text adventure with very simple graphical elements, based on the novel When Gravity Falls, with Islamic elements instead of the usual Asian ones. While almost entirely forgotten today, it’s an interesting piece of gaming history both for its technical side, with elements such as NPC scheduling, and for featuring some of the earliest gay/trans characters on PC.

Ideas in general were the genre’s strength, even if the games they were in drew more overall from Blade Runner’s aesthetics than cyberpunk philosophy. Metal Gear creator Hideo Kojima, for example, created Snatcher, a totally original story about a detective with a mysterious past hunting humanoid robots in the futuristic Neo Kobe City. Even more blatant was Sierra’s Rise Of The Dragon, a Chinese-themed adventure set in Los Angeles that named its hero ‘Blade Hunter’. Nothing, however, was ever quite as shameless as Access Software’s Mean Streets, which didn’t just lift Blade Runner’s style, but shamelessly pinched one of its advertising posters.

Future shocks

When games broke free of that, the results could be fascinating. DreamWeb was one of the earliest to make waves, though not so much for the fact that your character was a potentially insane serial killer being guided by his dreams, as for the inclusion of a sex scene showing a few scandalous pixels of penis. It was an interesting game though, at least for the first few missions, before everyone involved unfortunately seemed to get somewhat bored with the concept.

Other prominent games of the '90s included Origin’s Cybermage: Darklight Awakening, arguably the most '90s name ever, the original System Shock, interactive movies with names like Angel Devoid and BurnCycle, and of course, the opening disc of Final Fantasy VII, which eschewed traditional fantasy for dark alleyways and the evil Shinra corporation. While it wasn’t on PC, CD32 game Liberation: Captive II also deserves a mention. It was an RPG about freeing prisoners in a huge, fully explorable city. Almost impossible in scope then, it’s still impressive to consider today.

Three of the more interesting failed experiments came from creators John Antinori and Laura Kampo: Bloodnet, Hell: A Cyberpunk Thriller, and (minus Kampo) Ripper. They’re not great games, but they represent some of the most earnest attempts to Make Cyberpunk Work. Bloodnet mixed the traditional elements with vampires, in an open-world adventure/RPG in which you regularly had to feed to maintain your sanity, and any NPC was a potential target. Hell was about a future government working with demons to damn their enemies (though it was really a virtual reality scam). Finally, Ripper brought Jack the Ripper into the future, with some hilariously campy FMV, and a huge cast of actors such as Christopher Walken and a pre-fame Paul Giamatti.

Alas, it wouldn’t really be until Westwood returned to the genre with its official Blade Runner game, and Ion Storm released Deus Ex, that the genre would truly get its dues on PC.

Even then, it’s been a bumpy ride. Until CD Projekt, we’d never seen an official Cyberpunk game, despite the P&P having been written back in the very Web 1.0 era of 1988. And while there had been pretty good console RPGs based on its main competitor, Shadowrun (cyberpunk, but with elves and trolls and magic), it wouldn’t be until over a decade later that Microsoft finally released a PC one. Unfortunately, this one wasn’t an RPG, but a mediocre team-based FPS that fans mostly loathed. It wouldn’t be for several more years that Shadowrun Returns would save the series’ reputation with a trilogy of excellent games. The second one, Dragonfall, is especially good.

Metaverse and beyond

Despite the struggles, cyberpunk has always been a part of PC gaming—elements borrowed, inspiration drawn, cool things cherry-picked, whether something simple, like the anime stylings of Bungie’s Oni, the cool approach of hacking in Introversion’s Uplink, or the sprawling dystopia of Syndicate and Syndicate Wars, in which you’re the evil corporation instead of the oppressed antihero.

Along with Blade Runner, one particular work has repeatedly cropped up in gaming culture—Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash. While part of the genre, it largely satirised cyberpunk tropes, as best summed up by the main character being a hacker pizza delivery boy called ‘Hiro Protagonist’. Its central concept, a virtual world called the Metaverse, became an inspiration for what the internet could be—popularising, for instance, the word ‘avatar’ as a name for a character, and the dream of a user-created space in which code and imagination could craft any landscape. This, alas, never happened, with the best attempt, Second Life, quickly descending from utopian dreams of virtual universities and truly world-wide rock concerts into a virtual universe of porn shops.

Still, the dream defined both an idealised future for the internet and gaming in general, that we’ve seen explored in everything from MMORPGs to VR. Microsoft’s Xbox Live was heavily inspired by the novel, for example, with its creators given copies to read as homework.

There’s definitely something endearing about that: while cyberpunk as a genre may have often been marginalised in gaming next to newer, shinier visions of the future, it was helping define the future long before the likes of Deus Ex brought its nihilistic visions mainstream.

Now, in an era of indie creators facing off against huge publishers and platform holders, it has new meaning—the establishment that wants more than just your money, rebels creating art, and the internet as the last battlefield where David can fight Goliath. It may not be dark alleyways and rainy cities, but gaming doesn’t really get much more cyberpunk than that. Unless, of course, David finally upgrades to a katana.