How one phone call saved a tiny new studio and gave the world System Shock 2

Irrational Games co-founders Ken Levine and Jonathan Chey on the immersive sim's rollercoaster development.

"I was heartbroken," says Ken Levine. "I went away with my girlfriend and some friends up to Maine for the weekend. They were all having fun, but I remember thinking my life was over."

It was 1997, and just a few months after Levine, Jonathan Chey, and Robert Fermier founded Irrational Games, it looked like the company was about to collapse. The trio had left Thief studio Looking Glass after a wasted 18 months working on a Star Trek: Voyager tie-in that was suddenly aborted, leaving Looking Glass in "financial and creative disarray."

We just had to start building the game, because there wasn't any time to prototype.

Jonathan Chey

The young, hungry group wanted to test their skills and run their own project, and scored a contract to make the singleplayer portion of FireTeam, an online multiplayer strategy game. But shortly after they went independent, the deal fell through. They were out of work, and Levine was sure he'd blown it.

"That was really scary. I'd just got into the industry, I'd quit my dream job to start this thing, and then it was already not working out," he says. "I figured it was back to graphic design and computer consulting… I thought I'd missed my shot."

Irrational scrambled to create a top-down strategy game to shop to publishers, but most were unwilling to take a risk on it, and those that liked it didn't have enough money to fund the idea. It looked like the dream was over.

"And then the phone rang."

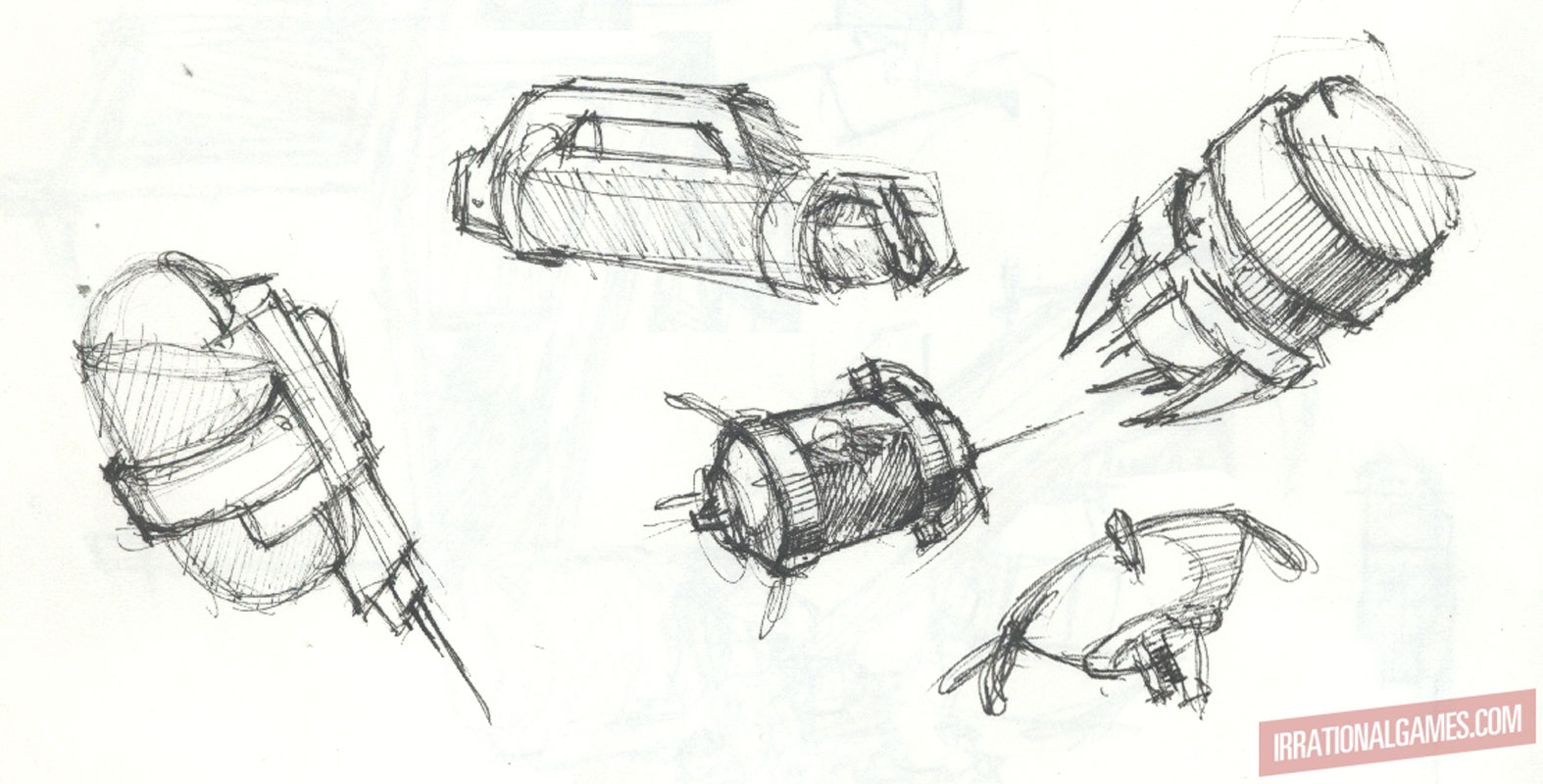

It was Looking Glass co-founder Paul Neurath, who threw Irrational a lifeline. Looking Glass had built an engine for Thief: The Dark Project, and he wanted to spread the cost by making other games with it too. Irrational, who knew the engine, seemed like a natural fit, and so Looking Glass asked them to come up with an idea for a game.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

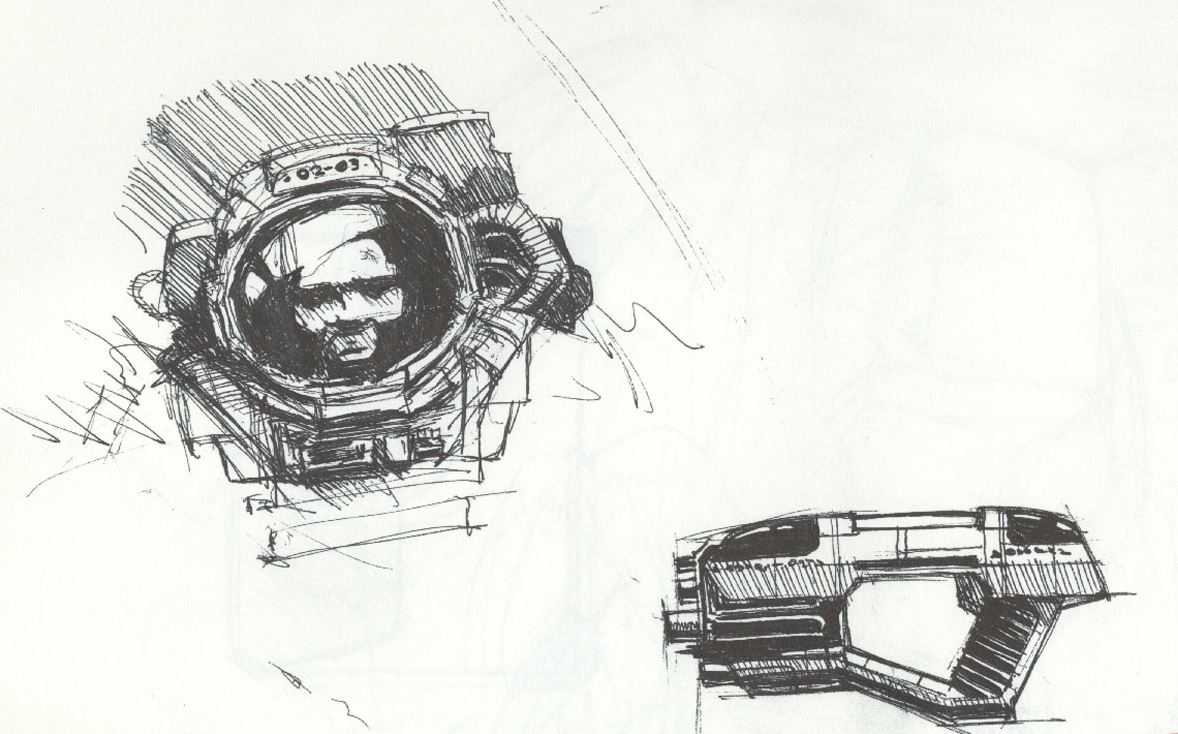

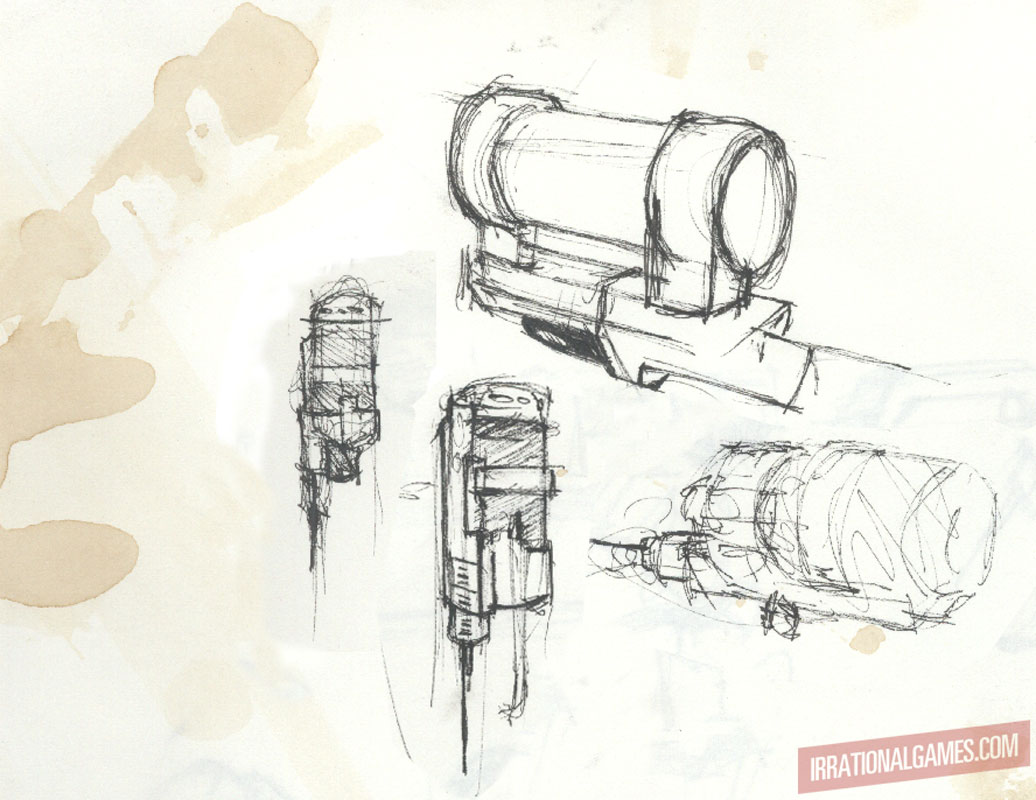

After Irrational built a crude prototype of an RPG-shooter hybrid—Levine says the team mastered how to show it off "just exactly the way where it wouldn't explode"—Looking Glass presented it to EA, which was impressed. And EA, it just so happened, owned the rights to System Shock, which Looking Glass developed in 1994. The team smelled an opportunity, says Jonathan Chey.

"[Our prototype] was just a science-fiction shooter game called Junction Point," he says. "I'm pretty sure it was our idea to bring back the System Shock license… 'hey, you guys already have this world, and it was really cool, why don't we use that instead of trying to invent an entirely new franchise here?'"

Just like that System Shock 2 was born and Irrational was pulled back from the abyss. But it was only the start of the hard work. Years later, System Shock 2 is one of the most celebrated PC games of all time. The human story behind it, as told by Ken Levine and Jonathan Chey, is less glamorous. They remember the six-and-a-half-day work weeks, the ending they had to cut, the game-breaking bugs they failed to fix, and wrestling with an unfinished game engine.

They also remember why, ultimately, it was all worth it.

'What are we doing?'

Unless you're Blizzard, and you have an alpha three years ahead of time... games aren't fun until quite late. System Shock 2 was certainly no exception.

Ken Levine

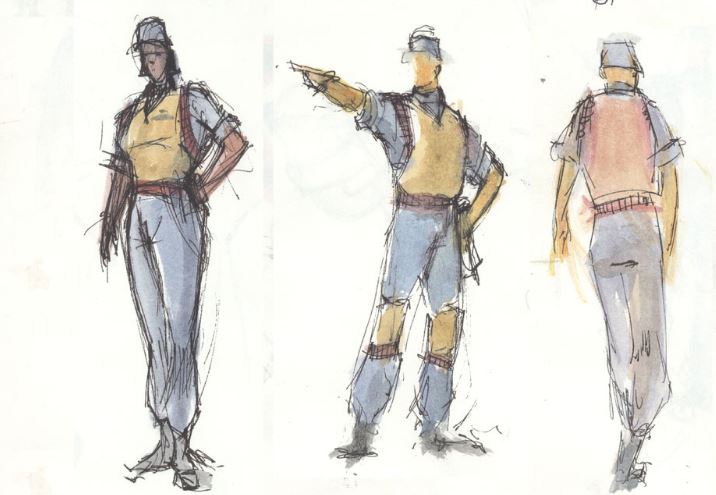

Irrational got roughly $650,000 to make System Shock 2, just over $1m in today's money. It wasn't a lot, and they had no choice but to hire junior developers: The many interfaces were all built by 19-year-old Mike Swiderek, who later worked on Bioshock and Bioshock Infinite.

They had just over a year to play with, Chey recalls, leaving no time to iterate. "We just had to start building the game, because there wasn't any time to prototype," he explains. "We were just trying to make it from the very beginning. That explains why there are things in the game that aren't that great: We didn't have time to redo it."

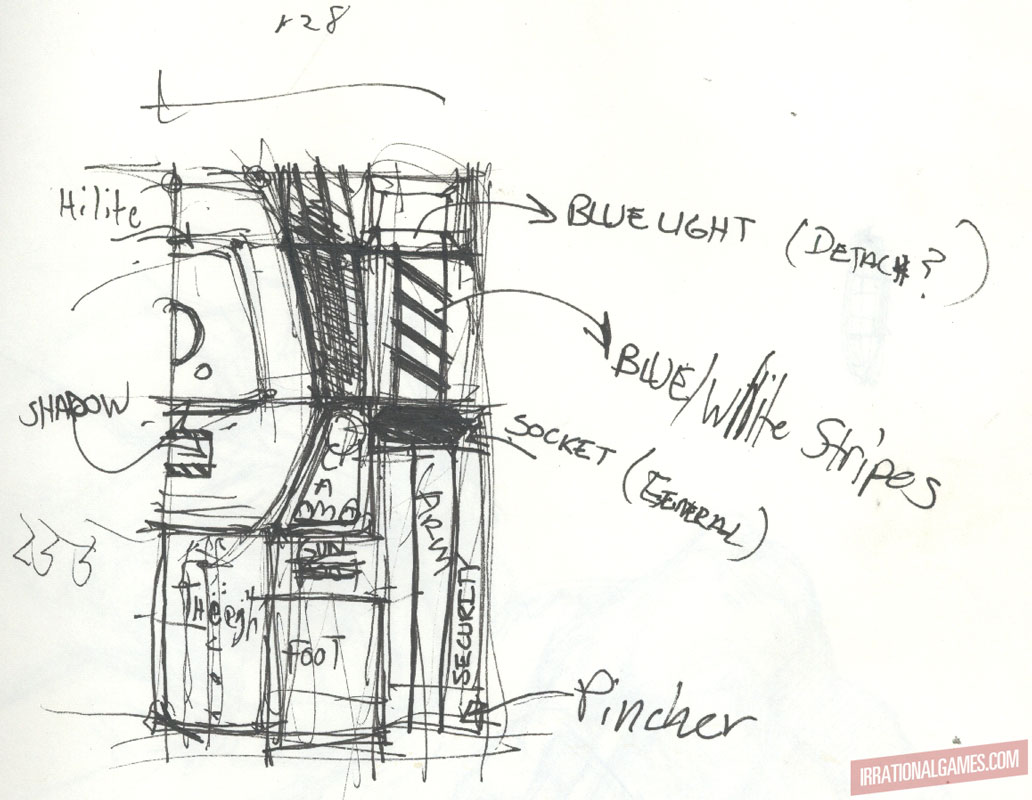

Chey worried about polish during development. The motion capture data was full of glitches that couldn't all be cleaned up, for example, leading to characters' hands getting stuck at strange angles. "You'd have these moments where you'd think: 'What are we doing? This doesn't look competitive.'

"This is the first game we'd done as a team. It was our company, our names and reputations as game developers on the line. I was very driven by fear of failure, I didn't want to embarrass myself…even though we were enjoying the work, there was a lot of tension and a lot of worry."

Levine was seemingly more relaxed. "I think I'm lucky in the sense that I can fall in love with things even if they're not worthy of that much love yet," he says. "That's an important thing for a game developer. Because games aren't fun. Unless you're Blizzard, and you have an alpha three years ahead of time that is anybody else's finished game, games aren't fun until quite late. System Shock 2 was certainly no exception."

There are still whole sections of the game Levine isn't happy with, including the character creation, which he says was too text-heavy, as well as the level set in the body of The Many, the biological hive mind created by antagonist SHODAN. It introduces lots of new ideas, and the team were too green to realize how much extra time it would take to do them justice.

Levine originally planned the level as a zero-gravity space walk between two ships, and remembers bringing the idea to Chey. "He just gave me this heartbreaking speech about how much work it would be, and of course he was right," he says. "I wasn't experienced enough to think that through."

Chey says that sums up the relationship between the pair: "He was like the idea generator, and I was like the filter."

System Shock 2's ending was initially very different, too. Levine imagined a complicated double-cross involving SHODAN but simply didn't have the resources or time to pull it off, in part because of how hard it was to make cutscenes, which were built in the engine.

Enemies could patrol and search an area on their own but it was difficult to make them perform specific actions, or even walk where the team wanted them to. Small changes in pathfinding or character movement could play havoc with these cutscenes, making characters walk, for example, to the wrong side of a desk. Chey says that "getting the camera work and the timing of things right when you've got this constantly changing [behavior] is really hard. That explains why the cutscenes were a little bit ropey, they were an enormous amount of work."

Levine's original ending needed a large cutscene, and was therefore unworkable, leaving him to rush out another idea. "I did the best I could," he says. "It wasn't strong, but people have been very generous and forgiving over the years about the ending. They don't mention it as much as the good parts, so I'm grateful."

The cramped schedule also meant bugs slipped through: Chey recalls one potentially game-breaking bug, seemingly still undiscovered, that he found after the game shipped. To defeat an enemy called The Many, the player had to first take out floating orbs, which were scripted to fly in circles. "If you had a framerate glitch, they could fly out of the level, and then you couldn't shoot them anymore, which meant you couldn't kill The Many, which meant you couldn't progress the game."

The bug could even occur before the player entered the room, which meant reloading an earlier save might not fix it. "That was the one thing that tortured me," he says. "I don't think I ever really heard someone complaining about it, but it was a horrible feeling to discover it and realise, we can't fix that now."

The short development cycle inevitably led to crunch. Chey recalls the workload being "insane": He was essentially working three jobs, managing the project, programming the AI and carrying out company administration such as payroll and taxes. "It was out of control. I was working six-and-a-half days a week, I don't really remember having a holiday during that time."

Levine recalls System Shock 2 being both "my life and my hobby. I didn't have a lot of friends, I'd go home on the weekend and those were long, lonely weekends. I'd rather come in and be at the office and work. Fortunately, I've since gotten married and got a dog and all that other stuff, but back then it was all I wanted to do."

The chaotic scheduling—which Chey partly takes responsibility for as project manager—was a hangover from the founders' time at Looking Glass, where "every project went massively over time, every project was really stressful at the end," Chey says. "It was a combination of not enough time, overambitious developers, and people that really cared about the product, so they were their own worst enemies in many ways."

Shooters were barebones, hyper-action focused. They weren't interested in storytelling, character growth or player choice.

Jonathan Chey

For Chey it got so bad that, when development wrapped, he realised he needed a change, and moved home to Australia to open a new branch of Irrational. "It completely burned me out. At the end of it, I was like: 'I can't keep doing this'."

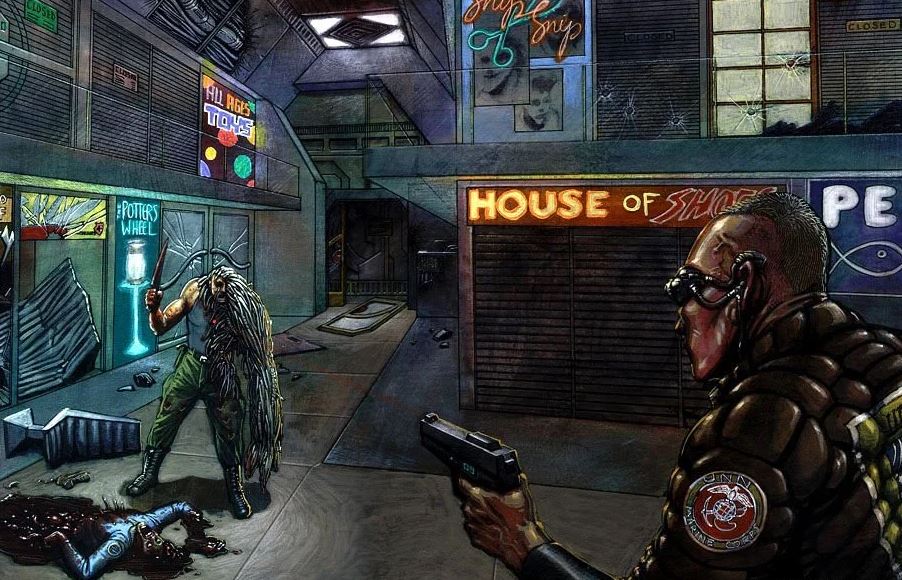

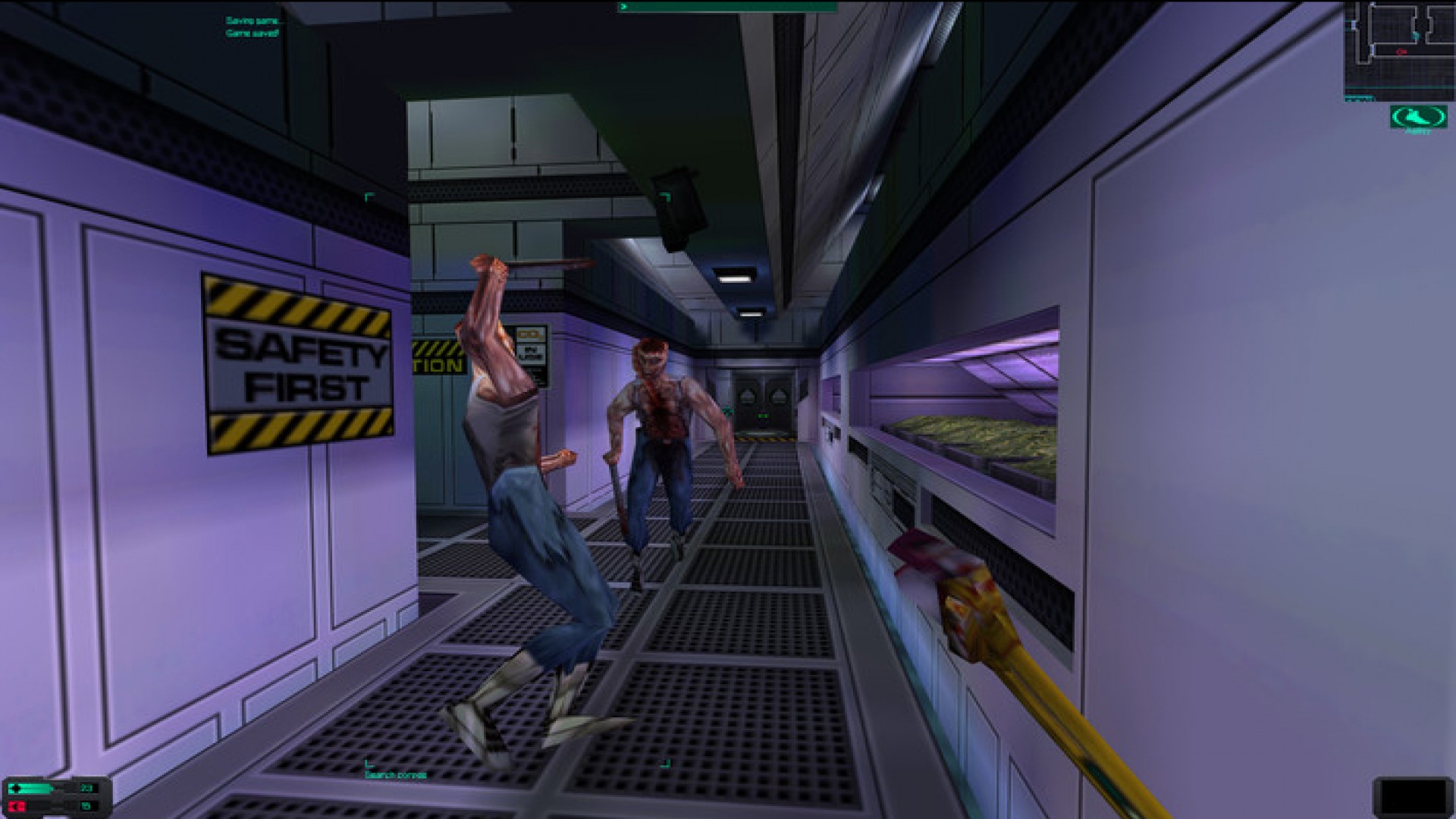

Despite the rough edges and long hours, System Shock 2's brilliance was slowly beginning to emerge. There came a time where Chey could look past the missing polish and see individual ideas—the storytelling, the player customisation, the stealth, the crafting, the exploration—coming together. "There was a richness to the game," he says. "[At the time] shooters were barebones, hyper-action focused. They weren't interested in storytelling, character growth or player choice, they were interested in satisfying, meaty combat. That's what made System Shock 2 interesting: it was a different take on shooters.

"When you put it all together you get something unique. I do remember playing it a month before we shipped and thinking: 'You know what, this is actually really working'. It's a pretty cool feeling when you play your game and you think, 'I'm enjoying this, I'm actually having fun.'"

The same feeling hit Levine when he stayed late to work on an opening cutscene. "I'd be in the office and I'd be trying to get something right. I'd be all alone, and I'd just hear the sounds [audio director Eric Brosius] had put in, and I'd see the Hybrid [enemy] run by and shoot the lady at the beginning. I remember thinking, 'Okay, maybe this is just me, but this feels kind of lonely and scary and cool.'"

For him, the brilliance of System Shock 2, and the reason it's still so revered, stems from three things: the blend of shooting and roleplaying, the emphasis on worldbuilding, and the player's relationship with SHODAN, who appeared in the original System Shock. He decided early on that he wanted to create a "frenemy" relationship, something he hadn't seen in games before. He wanted the kind of scenes he loved in movies, where the heroes and villains were locked in the same room talking, or on the phone to each other.

"I think I didn't know exactly what I wanted, and I wrote until I ran out of time, and made it as good as it could be," he says. "Once you get Terri Brosius' performance and Eric's treatment of that performance, you really have to work hard to fuck that up."

'The odd man out'

System Shock 2 wasn't a huge commercial hit but players and critics loved it, which is all the team had hoped for. Levine says publishers wanted to find out what the young team had in store next—Chey reveals Irrational received no royalties from sales, but that it gave them enough of a reputation that they could negotiate better deals for subsequent games. Even after creating the Bioshock series, System Shock 2 remains the high-point of his career, he says.

"It's a little bit harder for people to understand now, because everyone can make a game, the tools are out there. But back then it was amazing to me that I was being allowed to make games. It was like: 'Do people really do this for a living and get paid for it? And now I get to do it too? Shouldn't I be paying somebody to be allowed to do this?'"

For Levine, it was proof—to himself as much as anybody else—that he belonged. He confesses that early in development he felt like "the odd man out" because of his lack of technical background. "I kind of expected [Chey and Fermier] to wake up and be like: 'What are you doing here?'" The reception after release showed him, for the first time, that he could create games an audience would love.

"That's all I ever wanted. I didn't succeed as a screenwriter, and so this is my second bite at the apple, and there's probably not going to be another one. The fact it shipped and did as well as it did critically, that's one thing, and that's good, but just learning I could make things that people like—I didn't really know I could do that. That it would bring people joy, I didn't know I could do that. So it's hard to look back on it with negative feelings.

"Yeah, it was rough: We had no money, we were inexperienced, doing our company tax returns and contracts and all that other crap at the same time. The three of us were really stretched. But it was, I guess, kind of a beautiful experience."

Samuel Horti is a long-time freelance writer for PC Gamer based in the UK, who loves RPGs and making long lists of games he'll never have time to play.