Seed is a hugely ambitious in-development MMO that echoes EVE Online, Rimworld and The Sims

Powered by Improbable's SpatialOS tech, Klang Games sets its bar high.

"MMOs have come to a halt, so far as innovation is concerned," Klang Games co-founder Mundi Vondi tells me. "With Seed, we hope to change that."

To say Seed is ambitious is an understatement. Within minutes of booting up its pre-alpha demo, Vondi has namechecked The Sims, Dwarf Fortress and Facebook as just some of the driving forces behind its persistent simulation. Its universe is said to be "driven by real world emotion and aspiration", which in practice aims to one day craft an MMO world with, potentially, millions of residents. Building colonies from the ground up parallels the workings of Civilization, while the potential for story-generation echoes Rimworld. Within, characters will live out their virtual lives whether the player is present or not.

"If you think about Facebook, imagine your profile was removed every time you logged off," says Vondi. "That's how most MMOs are today. I think this will add the network effect that the likes of Facebook has, so we're trying to learn from that."

Hailing from a fine art, production and filmmaking background, Seed marks Vondi's first professional videogame project. Klang's other cofounders, Oddur Snær Magnússon and Ívar Emilsson, though, are ex-CCP employees who both worked on EVE Online. It's this collective experience that informs Seed's goals—even if what I'm shown isn't quite as sophisticated as what's promised down the line.

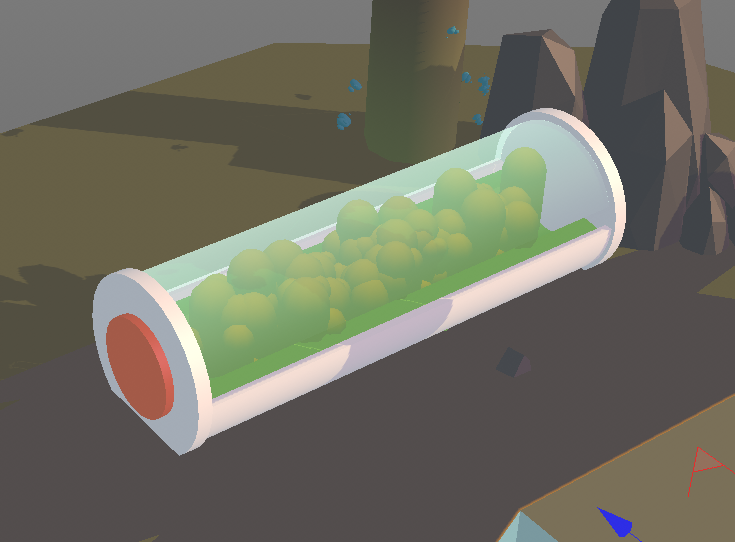

Powered by Improbable's cloud-based SpatialOS tech, the hands-off demonstration I'm given kicks off with a group of humans touching down on a foreign planet 1,000 years after Earth has died. From here, a familiar colony sim-building routine unfolds, where the player issues their AI-controlled civilians with tasks and directives such as gathering vegetation for food, or foraging materials for base-building. It's all very management-heavy, but Vondi assures me variables such as player mood and emotion are at the forefront of every decision you'll make.

"Even at this early stage in growing a colony, your civilians can get bad feelings that affect their behaviour—sleeping on the ground, for example—and these feelings can drive them towards certain traits," says Vondi. "If they're feeling great, they might become enthusiastic about the job, but on the other hand if their mental health gets really low, they might turn depressed or into alcoholics and other things like that."

From the outset, Seed lets players choose whether they wish to join an established community, or if they'd rather go it alone in the wilderness. Vondi reckons the latter should only apply to veterans of the genre, however those entering active societies should be wary of player-formed governments, judicial systems and economic infrastructures. Conflict sounds inevitable within the latter, and while it's unclear how confrontation will be resolved (or, crucially, if it can be resolved), maintaining good relations with your neighbours is of utmost importance.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"The sad part about most MMOs is when players enter the game, when they enter a player group or a clan, it takes a long time," explains Vondi. "A lot of players leave before they get that full social MMO experience. One of the things we do differently here is start you off in a community—you're immediately a part of a group from the get go. This should make everything easier, particularly for new players."

Speaking to Vondi's last point, I suggest that grind is something new MMO players tend to struggle with. With something so multifaceted, I ask what measures Seed has in place to combat this.

"Players can control up to ten players," he replies. "A lot of game design that's usually very tricky—like sleeping, disease, mental issues, ageing—they're pretty difficult if you're one character. But when you have ten you can actually do something with it. One can be sleeping, one can be somewhere else and so on. A lot of grind gets solved with this, so they basically work autonomously. They set their routines, and so they look through that and work on what their priorities would be.

"We're basically grouping together all these players and we can basically throw loads and loads of players into it. This means that we can hopefully, one day, have players building their own businesses and ultimately we want to see a world where people have furnished apartments, people are walking back and forth from their jobs."

Vondi returns to the idea of permanence in the player's absence by outlining a hypothetical scenario. Here, the player has signed out of the game and one of their characters has gone drinking in their local in-game pub. Inebriated, the character gets into a fight, gets into trouble with the law, and winds up in jail. By the time the player signs back in, their character is a few hours into an overnight stay, depressed and shunned by their peers. Vondi suggests real world notifications could alert the player to their characters' actions which they may or may not be in a position to respond to.

From here, the player might decide to rehabilitate their beleaguered pal or abandon them entirely. With nine other companions, perhaps it's best chalking this one off, or even swapping them out for a better behaved replacement. Substituting and maintaining multiple characters however raises the question: what sort of business model will Seed employ?

"We tie our payment model through our characters," says Vondi. "Because we're simulating our characters continuously, they take up a certain amount of the CPU. That's where we try to monetise: you basically pay per life, and you buy Seed implants. We want to open it up in a way that players sell these Seed implants on the player market. In theory, this should work well. But it could be a total disaster [laughs]. I can't confirm that either way.

"That would allow players to play completely for free while others are buying perks or implants and then selling them through the player market. The price will obviously fluctuate, so if someone is overselling implants, someone will eventually undercut them and [stabilise] the market. That's how we try to balance that out. Players who have a good set up, who are making a lot of money in the game can actually use the soft currency to buy those implants."

Since first showcasing Seed to the press at Gamescom in August, Klang has grown the game's landing planet surface by "roughly 2,000 percent" and has applied a new AI system that allows its characters to behave more organically.

Day-to-day, adding terrain and designing a new modular, streamlined building system takes priority, while long-term goals include the aforementioned player market and a character health system—which considers different forms of injuries and disease, and the knock-on effects these might have on colonies. "Once the health system is more structured," says Vondi, "we can focus on combat, as combat obviously affects health."

Again, Seed is a remarkably ambitious undertaking that, despite looking and sounding great at this stage has a very long way to go. If it can achieve half of what it hopes to, it will be onto something good—my main concern is that it's reaching too high.

Klang Games is however aware of the pressure it's putting itself under, and is cautious to avoid becoming overwhelmed.

"One of the biggest challenges of creating Seed is to make sure that we don't fall into that trap; this is something we have to constantly be mindful of," admits Vondi. "We're first focusing on the core systems in order to get them right. But, it's all about the balance between polishing the core experience and delivering on new features.

"Throughout the development process, we're making new discoveries, which is extremely exciting! We're making sure that the core playing experience will be fun and functional as soon as possible, but at the same time, keeping an open, flexible mind to adapt to new findings."

As it stands, Seed hopes to enter beta testing in late 2018, and will pursue full release after that.