NFT expert imagines a hopeful future where poor people serve as 'real-life NPCs' in games

If you thought gold farming was bad, wait until you see this vision of the future.

Efforts to integrate NFTs into videogames have been largely unsuccessful for a few reasons, but essentially it can be boiled down to two primary points:

1. They don't add anything of value, and

2. There's a nonzero chance that the digital stuff you own will be stolen from you, aka a 'rugpull.'

And that's without even considering the environmental damage caused by NFTs. But as seen in a new Rest of World report, that's not preventing NFT evangelists from coming up with even worse ideas for the future.

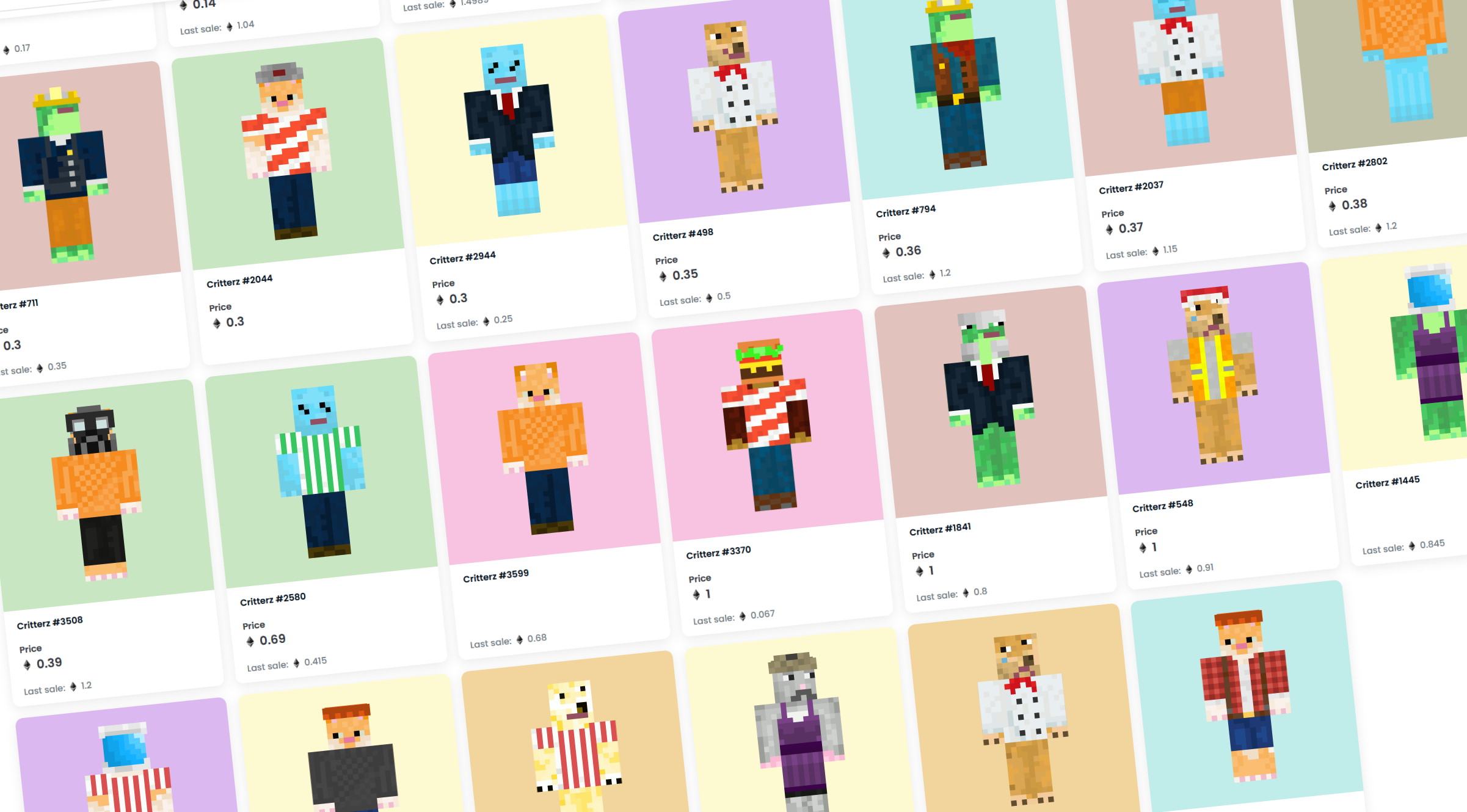

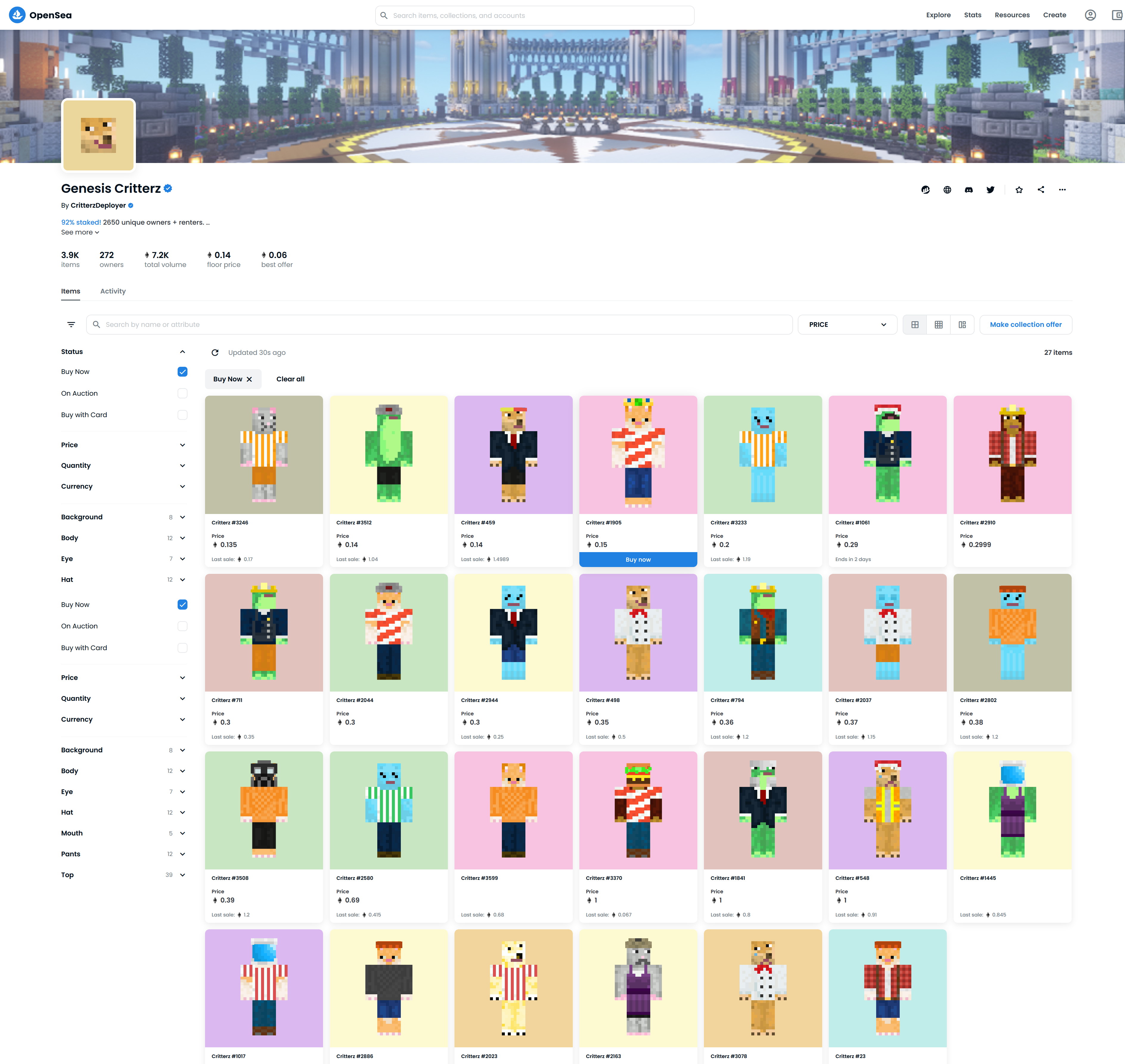

The bulk of the story by the nonprofit journalism organization is about a Minecraft-based NFT game called Critterz, which enjoyed enough success in its early days that some players began hiring others to help build their in-game ownings in exchange for a cut of the profits. One such high roller, who goes by the name Big Chief, had "his team"—made up mainly of kids in the Philippines—collect building materials for a casino, which he then paid "professional Minecraft builders" $10,000 to actually create.

"I have a lot of kids that play for me, and they play because they want to make extra money in a country that’s really just locking them down," Big Chief explained. People in the Philippines were willing to play the game this way, he added, because "they were able to earn just enough where it was worth their while."

It wasn't just play, though. Big Chief said members of his play-to-earn guild were required to put in eight hours a day, the equivalent of a full-time job, in order to recover the costs of NFT purchases—the digital "plots of land"—and maximize revenues as quickly as possible. Still, he said was "annoyed" by the suggestion that his exploitation of disadvantaged people in poor countries was, you know, exploitation.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"I couldn’t tell you what the hourly rate comes to, but I could tell you that people make very little money and the cost of living is very low in the Philippines," Big Chief said.

But as Critterz grew in popularity, its value began to drop: Big Chief said players were selling their $BLOCK tokens used in the game rather than holding them "because they need money to live," which combined with the increased number of players created a token glut that drove prices down. Following the trajectory of most cryptocurrency in 2022, $BLOCK sunk from a high of 85 cents in January to just 3 cents in May. The wheels didn't really come off, though, until July, when Mojang declared that NFT integration into Minecraft is "not something we will support or allow." That cut the value of $BLOCK, already dramatically diminished, in half. Earnings dropped, player counts fell off, and at this point the future of Critterz is uncertain at best.

Big Chief understandably bemoaned his loss—that is, the loss of his ability to do so much good for others.

"I treated a lot of these kids like they’re my kids, so it’s kind of sad now that I can’t really offer them much," Big Chief said. "Before, I was really helping a lot of these kids, giving them an opportunity to make some extra cash for their families and it just kind of sucks that I can’t really do that right now."

Luckily, for him at least, people are coming up with fresh ideas for how citizens of the Third World can be put to productive use by wealthy Westerners. Mikhai Kossar of blockchain gaming consultant Wolves DAO, for instance, suggested that they could be added to the background of videogames for the amusement of other, presumably wealthier players.

"With the cheap labor of a developing country, you could use people in the Philippines as NPCs, real-life NPCs in your game," Kossar said, apparently seriously. They would "just populate the world, maybe do a random job or just walk back and forth, fishing, telling stories, a shopkeeper, anything is really possible."

It's an odious idea, perfectly in-character for the NFT field, and literally the dictionary definition of exploitation: "Selfish utilization … especially for profit." As much as I hate to admit it, it's also not at all outside the realm of possibility. Paying people to do the heavy lifting in your videogame of choice is nothing new—most of us are at least passingly familiar with the practice of gold farming in MMOs—but the introduction of real money into these systems only encourages bad behavior. It's dystopian, but also foundational: As long as real money is involved, there will always be people willing to pursue it, and there will always be others eager to take advantage of them.

Andy has been gaming on PCs from the very beginning, starting as a youngster with text adventures and primitive action games on a cassette-based TRS80. From there he graduated to the glory days of Sierra Online adventures and Microprose sims, ran a local BBS, learned how to build PCs, and developed a longstanding love of RPGs, immersive sims, and shooters. He began writing videogame news in 2007 for The Escapist and somehow managed to avoid getting fired until 2014, when he joined the storied ranks of PC Gamer. He covers all aspects of the industry, from new game announcements and patch notes to legal disputes, Twitch beefs, esports, and Henry Cavill. Lots of Henry Cavill.