Lightforge Games' social RPG is one of the most exciting things happening in the genre right now

A collaborative storytelling RPG that draws on player creativity.

My already rapacious hunger for RPGs has only grown more intense this year, even after being very well fed thanks to the recent summer of RPGs. I'm constantly snacking on TTRPGs, MMOs, CRPGs, sandboxy roleplaying adventures—my greed knows no bounds. And now here comes Lightforge Games, a studio founded by folks with CVs that include Blizzard, Epic, BioWare and ZeniMax Online, with what I can only describe as a roleplaying feast.

We covered the formation of Lightforge back in 2021, where CEO Matt Schembari told us it was "looking to combine elements from Minecraft or Roblox with tabletop RPGs to form a new way to play roleplaying games." And now, a couple of years on, I've been given a glimpse of what the team's been doing to make its grand ambitions, where it wants to "revolutionise RPGs", a reality.

It's still early days, and the game has yet to be blessed with a name, but I confess that I'm already fascinated. What Lightforge is making is a chimaera that draws from tabletop RPGs, sandboxes like Minecraft, platforms like Roblox and CRPGs like Baldur's Gate 3, with powerful but accessible creation tools that call to mind games like The Sims. It's a lot to take in.

This is not a game that's easy to define, but at its heart it is a collaborative storytelling RPG. Imagine a tabletop game, with a GM and players, but they are all on an equal footing. They work together to create locations and quests and storylines, rather than the GM taking charge and setting up scenarios for players to react to. These locations can be created by the group or shared by other players, and augmented on the fly. And while Lightforge will give groups a narrative framework, the bulk of the storytelling will come from the players themselves, as they chat and debate and work through the adventure.

"Players are in full control of the story wherever it goes," Schembari tells me. "So what we're ultimately making is a videogame where what you're saying and what you're imagining is just as important as what you're doing on the controller. And you can really take the story in any direction. The default way to play is that you get together with some friends and you build out a quest together. You use some prompts to basically Mad Lib together what a quest could be. You use the game tools to create the quest, the space of the quest itself, and then you play it out to see what happens."

Party on

It has the trappings of a TTRPG, with dice, a GM (though the role is named "guide" here), lots of flexibility and plenty of social components, but the level of collaboration sets it apart from most games in the genre. In a TTRPG like D&D, you often find yourself negotiating with the GM, asking if you can do specific things, while the GM will also have knowledge that you don't. This isn't how it works here. Players don't need to ask permission to do things, and they have the same knowledge as the guide, like where monsters are placed and the layout of dungeons. "The really interesting part," says Schembari "is what happens when you unravel things; what happens when you react and start talking about where that story can go."

Players are in full control of the story wherever it goes.

Matt Schembari

One of the benefits of this system is that it's designed to take some of the burden off the guide. In TTRPGs, it's the most challenging role, usually demanding a lot of prep time and an excellent grasp of the rules. There's a lot of cognitive burden placed on a GM. Here, though, the guide is almost a member of the party, working together with the other players to craft a story. Where it really clicked for me was when Schembari described the guide as the party's "tank", in MMO parlance.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"We actually view the guide in our game like an MMO views a tank. So it's a role that does require a little bit more knowledge of the game—a little bit more, not a lot more. It's a role that requires a little bit more leadership in the party. You need someone to do it. But it's not playing a different game. It's still fun, it's still joyful, you still get to experience the game, and you're not having a very different perspective than the others."

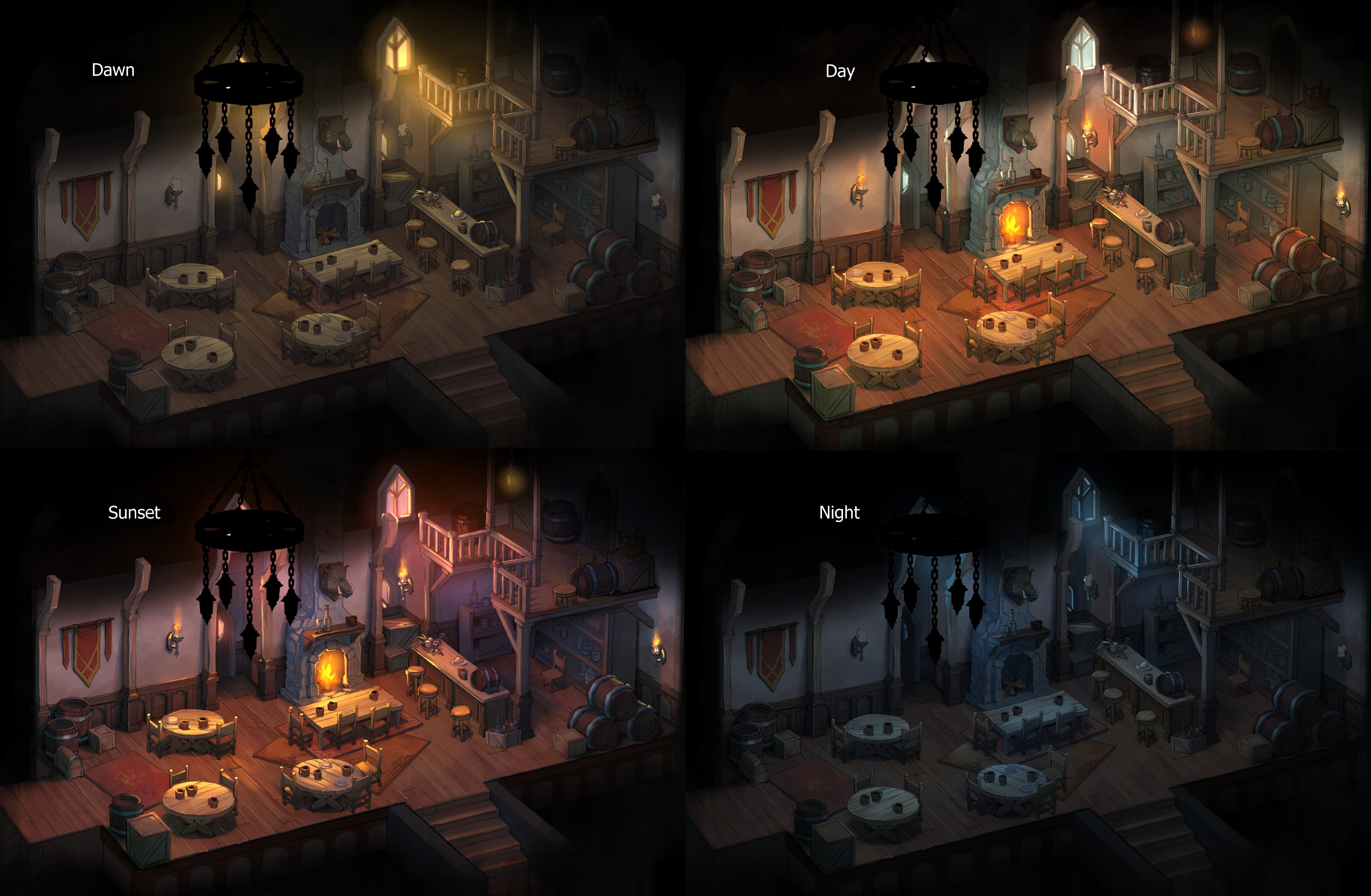

Initially, when we first started chatting, I imagined the game as looking something like a digital tabletop game, like Roll20 but maybe a bit prettier. The reality is that it looks like a modern videogame RPG with fully realised locations, weather and realistic lighting. And all the creation functionality is built into the game rather than separated into an editor mode. Everyone has access to it at any time.

"So people, when they get together and are playing, can literally modify the world at any time based on the things that are happening," says Schembari. "So if you wanted to literally change the terrain, you can. If a player was trying to do a find check, and they rolled really well and wanted to see if there's a secret door, for example, you'd be like, 'Yes, there was a secret door right there,' and you can just place it down. So I think that really our tools are probably more akin to something like The Sims, where it feels like a videogame form of creation and of editing and modifying the world."

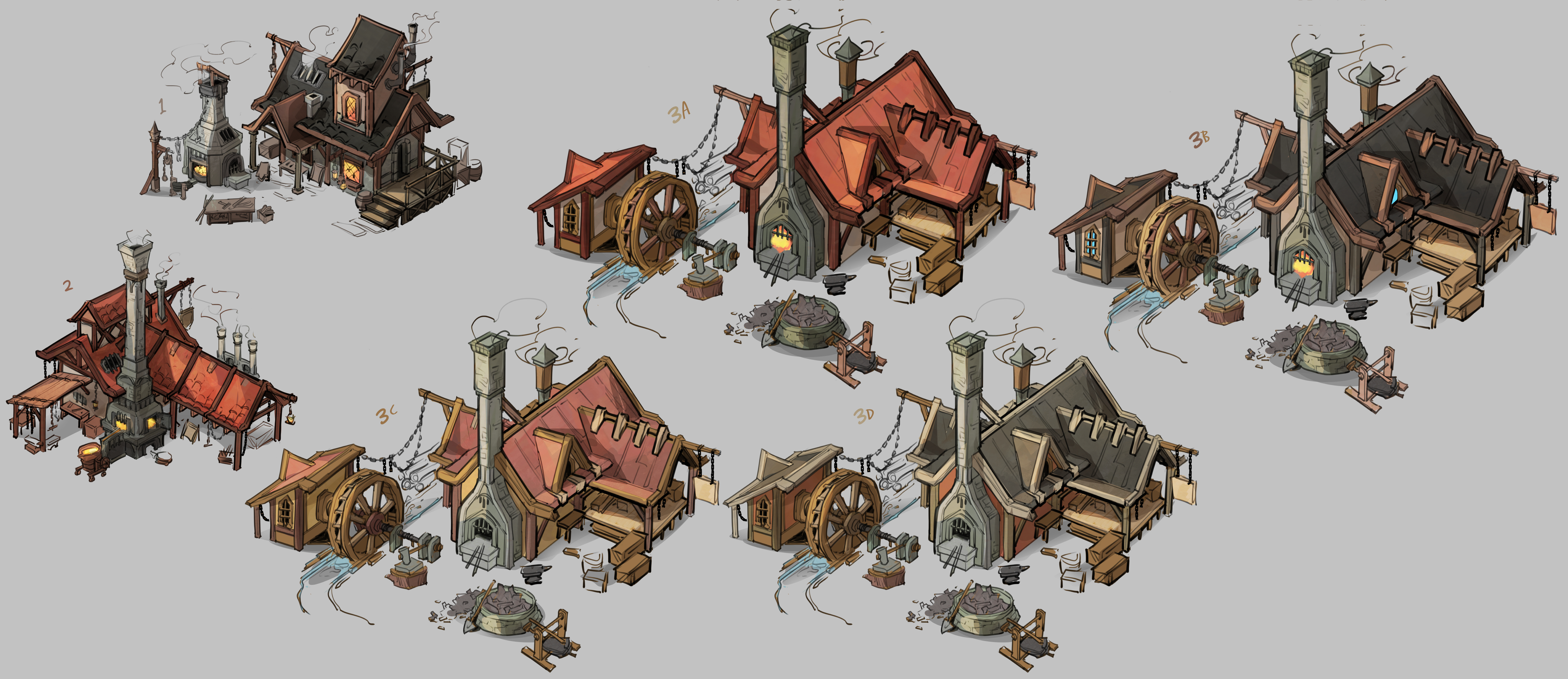

New objects can be dropped in as you progress through a quest, new NPCs can be summoned, objects can be lit on fire—the latter of which is connected to the Twist system. "You can literally take any object in the game and twist it," says Schembari. That could mean turning it into an illusion, making it a giant version of itself, or transforming it into a statue. It's even possible to make a brand new location on the fly from scratch, though Schembari thinks it will be less likely players will do that, as the focus is on a single scene at a time. But it's still something a party could do if they wanted to, and while it might sound like a big task, it's actually incredibly simple.

Fantasy builder

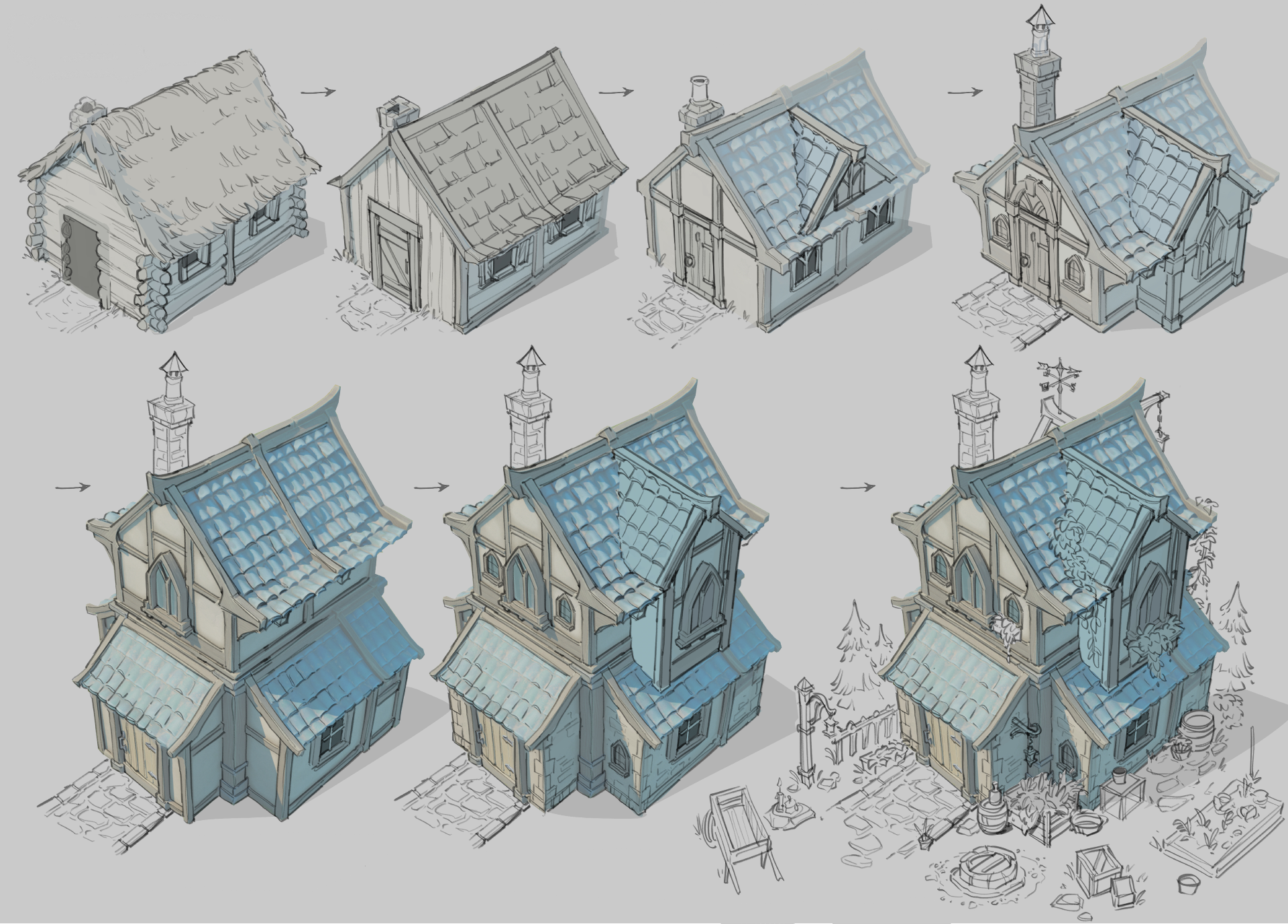

At this point, Schembari shows me some footage of a location being created. The video has some cuts, but in just a couple minutes this blank canvas becomes a striking forest scene full of buildings and props. Much of this is done by simply painting the scene, from the grass, trees and paths, while props can quickly be plonked down and the weather and time of day can be changed at the click of a button. The video is just over two minutes long, and Schembari tells me that it took only five minutes to create the location.

The game also makes some choices for you, fixing things that won't work, for instance, so players don't have to worry about navigation or collision. It will also pick certain ambient music depending on the time of day, but everything can be overridden. As well as starting with a blank canvas, you can also edit templates, from taverns to dungeon rooms to cemeteries.

While the functionality doesn't exist at this pre-alpha stage, the plan is to let players share their creations, too, making it even easier to craft an adventure. The team is a big fan of "zero prep" systems, so Schembari wants "people to be able to hop in and not have to worry about making things or doing homework for hours in advance," but that's ultimately up to the players.

When it comes to playing these adventures, it's very much like a TTPRG, with dice and cards and a dash of improv comedy. So you might decide, as a group, to trick a guard into thinking you're a bunch of merchants, where you make a sway check and then roll your dice, which exist physically in the game. And to make this experience as smooth as possible, Lightforge gives players a helping hand, to get them roleplaying even if it's not something they are used to doing.

Our perspective is you are a heroic magical character, you usually get to do the thing you're trying to do.

Matt Schembari

"One of the big things that we've done to really help with collaborative storytelling, to help folks who may be less experienced or completely inexperienced with this kind of gameplay, is this philosophy that we have called the on-ramp to roleplaying, where we help a lot," says Schembari. "So we've taken a lot of cues from any prompt based system, whether it's tarot or improv comedy."

At the core of this system is the game letting you build on your actions instead of just shutting you down by telling you that you missed your attack, for example. In the spirit of improv, it's all very 'Yes, And'. "Our perspective," says Schembari, "is you are a heroic magical character, you usually get to do the thing you're trying to do. However, when you do that thing, you might get a bonus to it. It might be extra effective, or you might get a complication with it." This way, the adventure maintains its forward momentum.

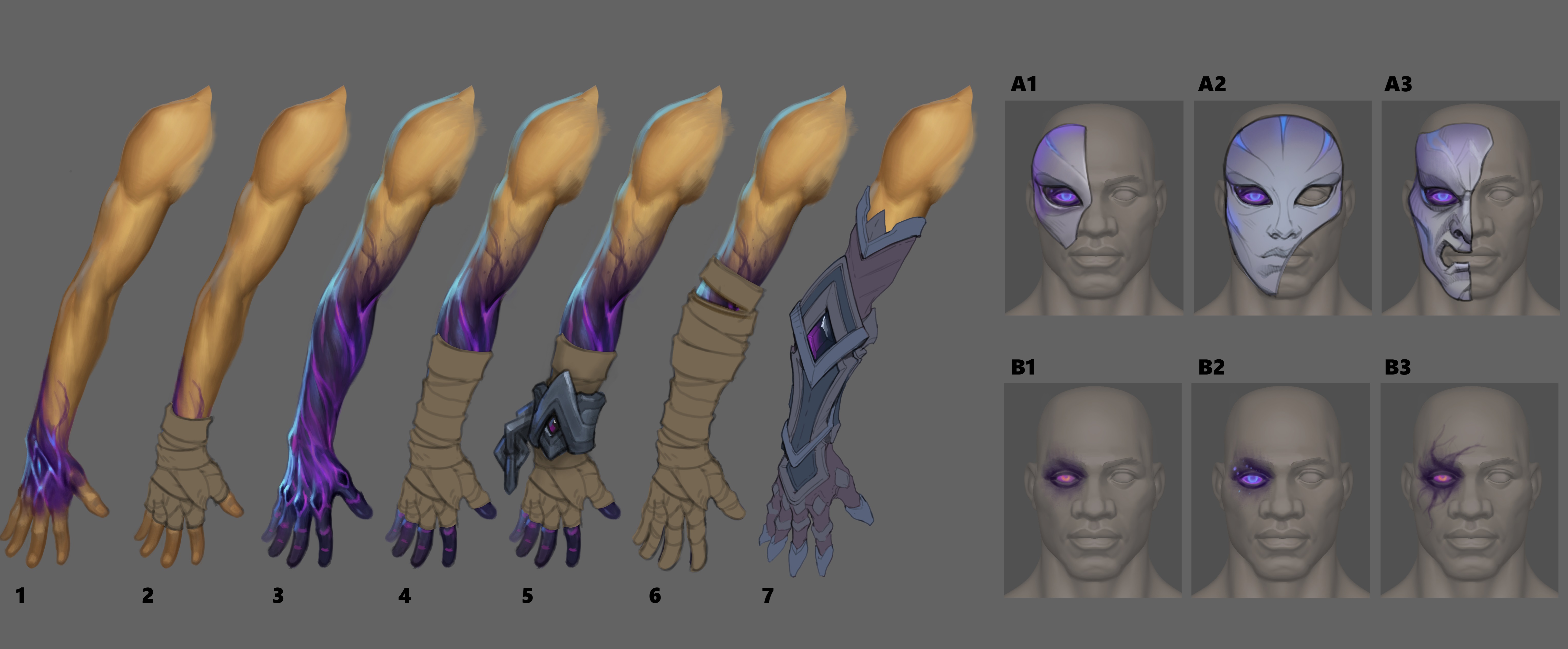

Schembari uses the example of the Ember, one of the character classes, casting a fireball spell. It's definitely going to hit, but you can get either a bonus (a boon) or a complication (a bane) depending on the roll. When this happens, context sensitive cards pop up on the screen offering different options, and you get to pick which one to play. This might transform the fireball into an AoE, make it stronger, or you can pick one that's not mechanical at all, like the Razzle Dazzle card, which just means you pulled off the attack with style. That can still come in handy, too, if you want to convince an enemy to join your side. Maybe they'll be impressed by your magical flourish and be more open to betraying their pals.

These fights are turn-based tactical affairs, but Schembari notes that there's less emphasis on the tactical side of things and more on the story. The fights are just another way to tell that story, rather than events that are technically challenging. And of course it's the guide controlling all of these foes, letting them use them to spin a more compelling yarn. Combat doesn't necessarily have to end with one side completely destroying the other, either. If one side is clearly dominating the other one, it creates what Schembari calls an "epic opportunity" or a "crisis", where combat ends and the players and guide can determine the outcome. Maybe your enemies run away, or maybe the party gets captured and has to escape from a prison.

When a session ends, the party can return to town: a central hub that you share with your player guild and develop over time. Schembari likens it to roguelikes like Hades, where you have this safe location where you can hang out and talk to people, and then you leave it to go off and have an adventure, and whether you succeed or fail, you end up back at town. "It starts off as just a small safehold in the wilderness that has almost nothing in it. And the point of the quests that you go on is to either follow opportunities to upgrade things and to add more to your town, or to deal with threats that are currently threatening your town, to prevent them from hurting someone, like taking away your blacksmith." So it serves a lot of different purposes: it's a social space, a progression system, and a narrative framework upon which you can build your own stories.

Throw out the rulebook

When Schembari was at Epic he was involved with Fortnite, and it's been just as big a source of inspiration as other RPGs—specifically the creative mode, where players can use the game's tools to make their own fun, just playing in a pure sandbox without too many rules. Minecraft and Roblox offer something similar: "Where you just get to play and express and have fun and be creative."

But even freeform games can benefit from a bit of structure, as long as it doesn't get in the way of players being able to express themselves, so like Fortnite, Lightforge is also considering a seasonal structure. Each season could have a main story beat, which players can drive forward through the prompts Lightforge provides, as well as their own improv skills. But even with prompts and story beats, players can really take the story anywhere. And the prompts themselves can even be the source of some surprises, taking the story in an unexpected direction.

Schembari describes a session where players had to stop some mercenaries from kidnapping a baby dragon, and the players managed to successfully convince them to back off. Unfortunately, they had to draw a bane card. The specific bane was "overreaction", so they convinced the mercs by telling them that the dragon was incredibly dangerous, inspiring the mercs to leg it back to camp to get reinforcements. The session was just a one-shot, but a follow up could have seen the players needing to deal with a whole camp full of mercenaries trying to kill the dragon they were charged with protecting. All because of this one bane card.

Working on games like Fortnite that give players access to creation tools has also revealed some of the inherent risks involved in creative sandboxes, and it's one of the reasons Lightforge isn't currently planning to let players create their own assets or upload their own art, outside of what they can make using the in-game tools. It's the ol' Time To Penis (TTP) issue. Give players the freedom to create whatever they want and they'll probably immediately make a massive phallus. "Every game I've ever worked on with any creation, the first thing that gets made and put on YouTube is something obscene," Schembari says.

Every game I've ever worked on with any creation, the first thing that gets made and put on YouTube is something obscene.

Matt Schembari

Even just letting players use developer-created tools and assets comes with a need for curation, not just to ensure that offensive content isn't being generated, but to ensure that it's easy for players to find the kinds of player-created locations they want to use. "From my time at both Epic and Blizzard, I've got a fair amount of experience with it and tackling it," says Schembari, "but it's not something that we have any answers to right now." The focus, at the moment, is nailing the basic loop and developing the progression systems, before the floodgates open and more playtesting begins.

So there's still quite a lot up in the air at the moment, from the business model to curation. Lightforge isn't even ready for people to know the codename they are using for it yet. But even at this early pre-alpha stage, there's a lot of promise here with this combination of collaborative storytelling and freewheeling playfulness. After having played what I suspect will continue to be the best scripted RPG for a very long time in Baldur's Gate 3, I'm very much looking forward to enjoying some improv adventures inside whatever Lightforge ends up calling their ambitious game.

Fraser is the UK online editor and has actually met The Internet in person. With over a decade of experience, he's been around the block a few times, serving as a freelancer, news editor and prolific reviewer. Strategy games have been a 30-year-long obsession, from tiny RTSs to sprawling political sims, and he never turns down the chance to rave about Total War or Crusader Kings. He's also been known to set up shop in the latest MMO and likes to wind down with an endlessly deep, systemic RPG. These days, when he's not editing, he can usually be found writing features that are 1,000 words too long or talking about his dog.