Is it worth cutting out Steam to sell indie games direct?

We spoke to the creators of One Hour One Life, SpyParty, and Overland about cutting out the middle-man.

On May 14, 2011, only one game was released on Steam: Jason Rohrer's tactical shooter Inside a Star-filled Sky. "It was on the Steam front page for five days," he tells me. "Releasing a game back then on Steam meant you'd instantly have an audience—I had all these new players that had never even heard of it before."

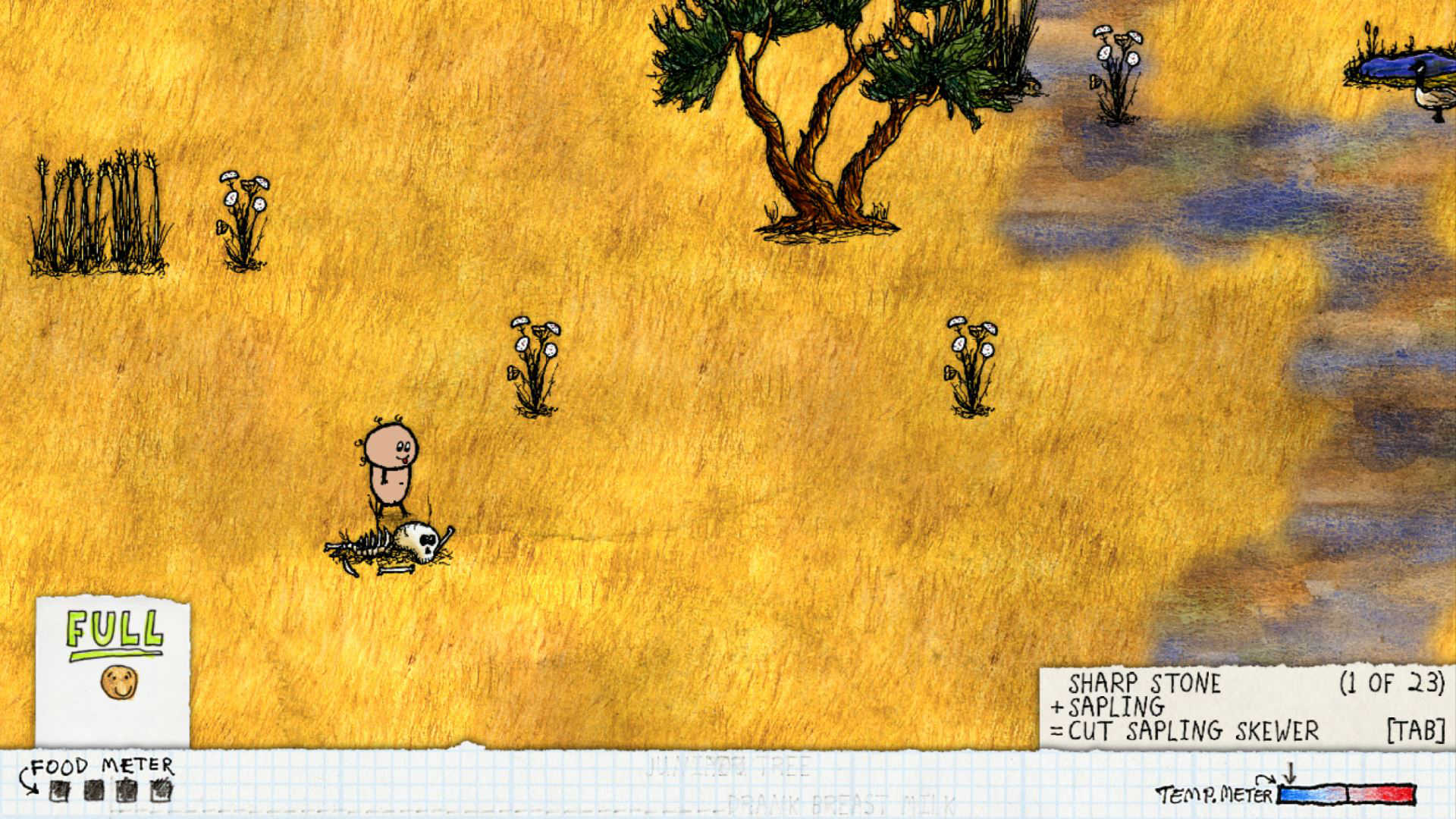

But things have changed a lot since then. Developers are pumping games onto Steam at an astonishing rate, making it harder than ever for individual games to stand out from the crowd. Last Wednesday, as 83 games came to Steam, Rohrer released multiplayer survival sim One Hour One Life to the public through his own website, opting to sell it to players directly.

He's no stranger to direct sales—only two of the 19 games he has made are on Steam—and other indie developers tell me they're keen on it too. So, what's the draw? And without the exposure that Steam and other sales platforms can offer, how viable is the model?

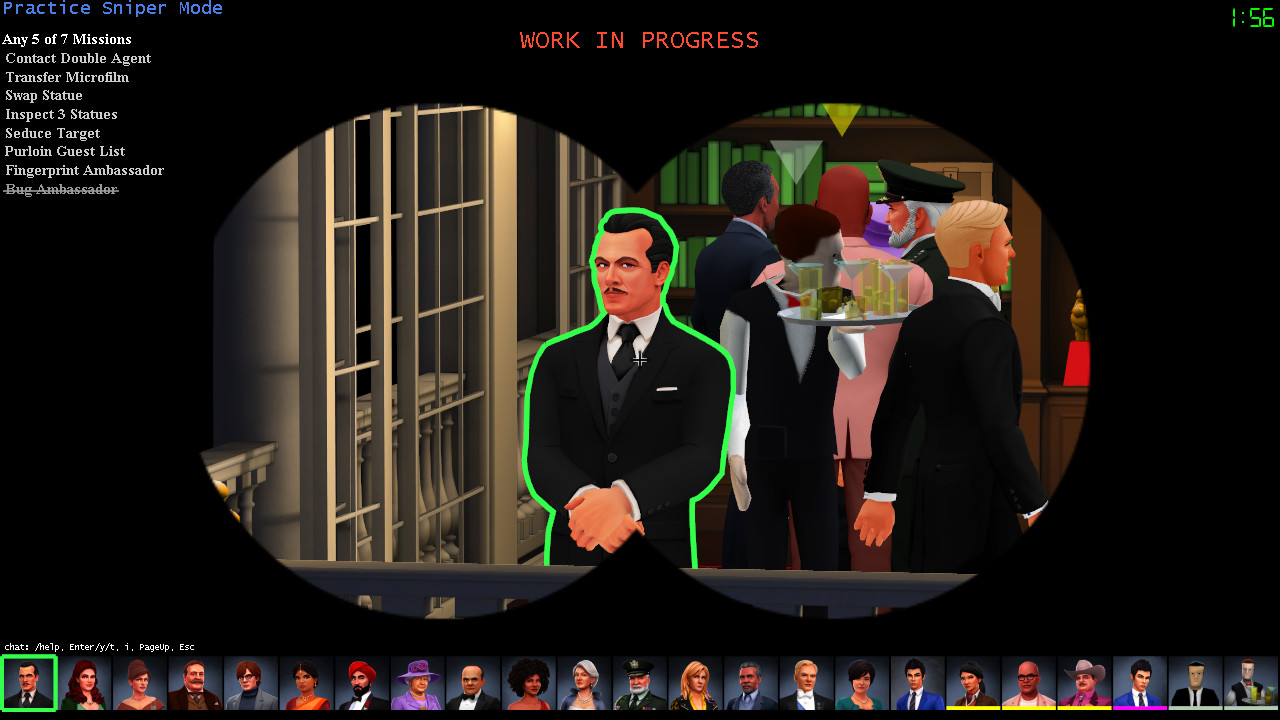

The most obvious benefit to a direct sale is that developers don't have to pay a cut to a third party, SpyParty creator Chris Hecker explains. He's been selling the long-awaited competitive one-on-one espionage game to the public through his own website since 2013, though is planning to send it into Steam Early Access soon. Valve will take a 30% cut of any sales he makes on the platform, compared to the 2.9% and change that PayPal takes when he sells the game himself. That's a "significant" benefit of direct sales, he says, but not the biggest.

I can send an email to everybody with the Mac build and say, 'Sorry about this problem, I'm an idiot, here's what you can do to fix it.'

Jason Rohrer

"The biggest thing is you get a direct relationship with your customer," he says. "I've had plenty of people request a refund on PayPal and in the notes they've said they can't get it to run. I can ask directly: 'Have you seen this bug workaround?' And they cancel the refund." That direct relationship has also allowed Hecker to cultivate a more "intimate, friendly" community that will give advice to newbies on the website's forums, moderate the game's Discord channel, and even help run stands at industry events.

That relationship with customers, and the ability to build a tight-knit community, is one of the main reasons Rohrer has chosen the model for One Hour One Life. His last project, MMO The Castle Doctrine, released on Steam 11 months after he started selling it directly, and the platform accounts for around half of the 21,000 units sold. But Rohrer has no way of contacting players that bought the game through Steam. "It's a little bit more impersonal, a little bit harder to manage a community," he says.

"When I'm hosting the game on my website I have a very direct relationship with the players. Last night there was a huge problem, I screwed something up royally in the middle of updating and the Mac build completely broke. I can send an email to everybody with the Mac build and say, 'Sorry about this problem, I'm an idiot, here's what you can do to fix it.' They get a personal email."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The DIY approach

Selling from a custom website means a developer has to build all the infrastructure around the game from the ground up: Rohrer runs multiple servers, sets up automatic game updates and created a user review system himself. But with that extra work comes more flexibility, which you can see best on One Hour One Life's website. Where its Steam page would look the same as every other game, the website tells players what the most popular food items in the game have been that day, shows them a counter of how many hours players have lived for, and links them to the wiki. "It's very customized. We want a counter showing how many people live past 55. No other game wants that counter. I have full control over it. It feels like a better fit, a better home."

However, for some developers the extra audience that Steam can offer (18 million concurrent users and counting) has become a necessity in order to survive. Hecker says that he's simply not making enough money selling SpyParty directly. "It's not paying the burn rate. I employ John Cimino, he's the artist, and I pay a full game industry salary. It's not making enough for that [right now]. It's very hard to not go on Steam and make a commercially viable game."

Obviously we love the idea of having our own everything, but there's a lot of weird overheads that maybe aren't obvious to people right away.

Adam Saltsman

Currently, without much fanfare, the game is selling anywhere between two and 20 copies a day through the website. Hecker is hoping that when it launches on Steam, the website will account for just 20% of overall sales, which would mean he starts making back the money he's spent on the project.

But even if the game were selling well enough through its website, Hecker says he'd probably stick it on Steam "eventually" so that as many players could play it as possible. "People like to buy games on Steam. It's a very trusted storefront, whereas if you go to SpyParty.com you're clicking a link on a website and entering your credit card number. So I can totally empathize with people holding off until it's on Steam."

Rohrer admits that he was also tempted by the chance of widening his player base. "Of course I have my doubts," he tells me. "Maybe I would've sold twice as many copies if I was Steam on release day, but I don't know. Yesterday I was thinking maybe I should go on Steam next week, but really what I need to do next week is draw 100 objects and put them in the game. Maybe Steam is something I'd do a year from now when I've put out a tonne of content and everyone's happy. But maybe not, maybe I won't have to." He adds that, as a one-man team, he's better set up to weather any periods of low sales than larger indie teams.

The itch.io compromise

Another developer that, like Hecker, is keen on the direct sales model but isn't ready to rely on it is Adam Saltsman. The founder of Night in the Woods publisher Finji is currently working on squad-based strategy game Overland. Initially he wanted to sell the game directly to get as much control over the process as possible, but decided instead to sell it through itch.io. "We wanted to go down the direct sales route… we talked to a bunch of studios that did their own direct sales setup, but it was pretty intimidating.

"Obviously we love the idea of having our own everything, but there's a lot of weird overheads that maybe aren't obvious to people right away. You want it to be easy for people to update their game, for example. Maybe you're not sure how you want to handle all the third-party payment processing stuff." He sees itch.io as a "compromise" between a larger, less flexible sales platform like Steam and a direct sales model.

For most indies, the draw of Steam is just too large to ignore. Early Access roguelike deck-builder Slay the Spire, which has sold more than 500,000 copies, is only available through Steam, Green Man Gaming, and the Humble Bundle, and developer Anthony Giovannetti says that selling through those platforms was a "no-brainer".

"We buy all our games from Steam or services like it, pretty much everyone we know does the same. That's just where the lion's share of the player base and money is. And so from our perspective it was just a no-brainer that we have to launch on those platforms," he says, adding that he doesn’t feel that Steam has made it any harder to manage Slay the Spire's community.

But Saltsman thinks that if Valve continues taking a 30% cut of sales on the platform that could start to put more developers off. "As we move into a period where platforms, for 90% of the games on them, absolutely fail to provide adequate exposure, the default 70/30 split seems pretty antiquated," he argues. "When you're a small, focused game with a small, focused team, getting to put an extra 10-20% of your revenue back into development has the potential to produce a much better game later on."

It's clear that players are willing to flock to well-made games that aren't available in any of the stores they're used to buying from—just look at the runaway success of Fortnite. So as Steam becomes ever-more saturated, it's not impossible to imagine more indies might try to tap into that and go it alone.

Samuel Horti is a long-time freelance writer for PC Gamer based in the UK, who loves RPGs and making long lists of games he'll never have time to play.