In Anodyne 2's 3D world, characters have 2D interiors of their own

It's a game that deconstructs itself as much as its characters.

At the bottom of a pond in the middle of the woods in Anodyne 2 there's an unassuming pipe. Dive into it, and it spits you out into a microcosm of a world built inside a floating of orb of polygonal tree-roots. In it, there's a village built out of tin cans, inhabited by an enclave of artisanal tree-crafters. I talk to one of them.

"I just joined the club," they say. "I'm still too nervous to touch a pair of shears. Besides, I haven’t even finished watching the 80-video training course!" Relatable, I think, but as I talk to the other inhabitants I realise I've stumbled into a tiny world wracked by impostor syndrome and creative self-doubt—it's like Spongebob but with anxiety. Anodyne 2 is, as they say, a whole dang mood.

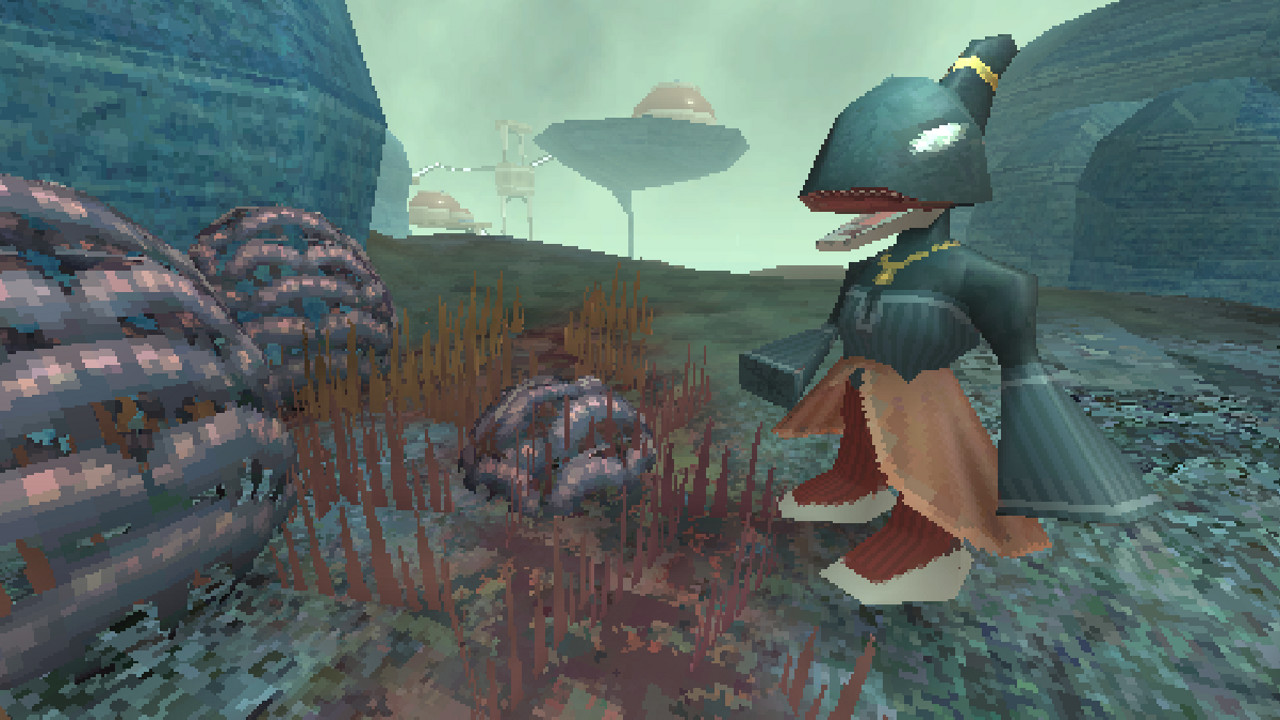

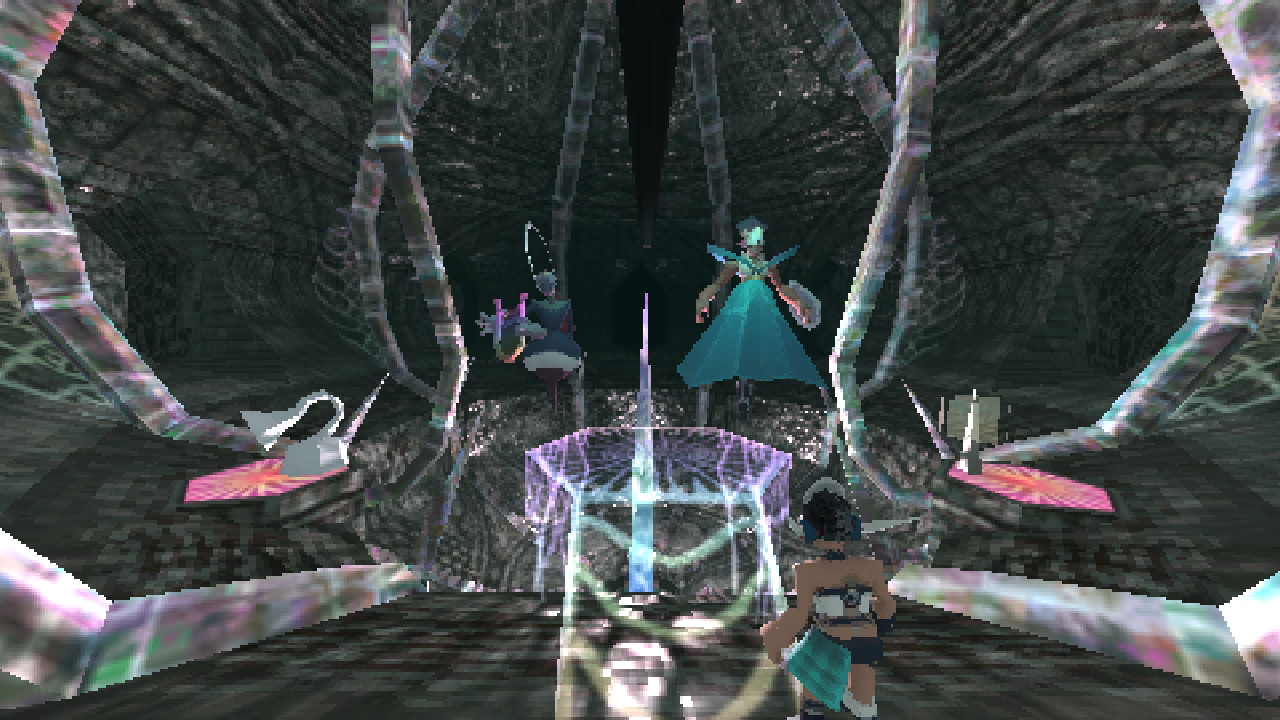

It's a bizarre bit of genre-blending alchemy: N64/PSX-styled 3D exploration through a surreal, dreamlike world; 2D SNES-styled puzzling and dungeon crawling; sometimes even a visual novel, delivering screenfulls of prose against a darkened background. It's a showcase of how to do more with less in games, an almost-abstract world full of lovably flawed oddballs that asks you to not only work out their personal issues, but pick at the polygon seams in the world as you explore and see what's hiding between the cracks.

A swarm of strange worm-creatures paraphrase Charlie Brown as they philosophize over the nature of footballs and failure

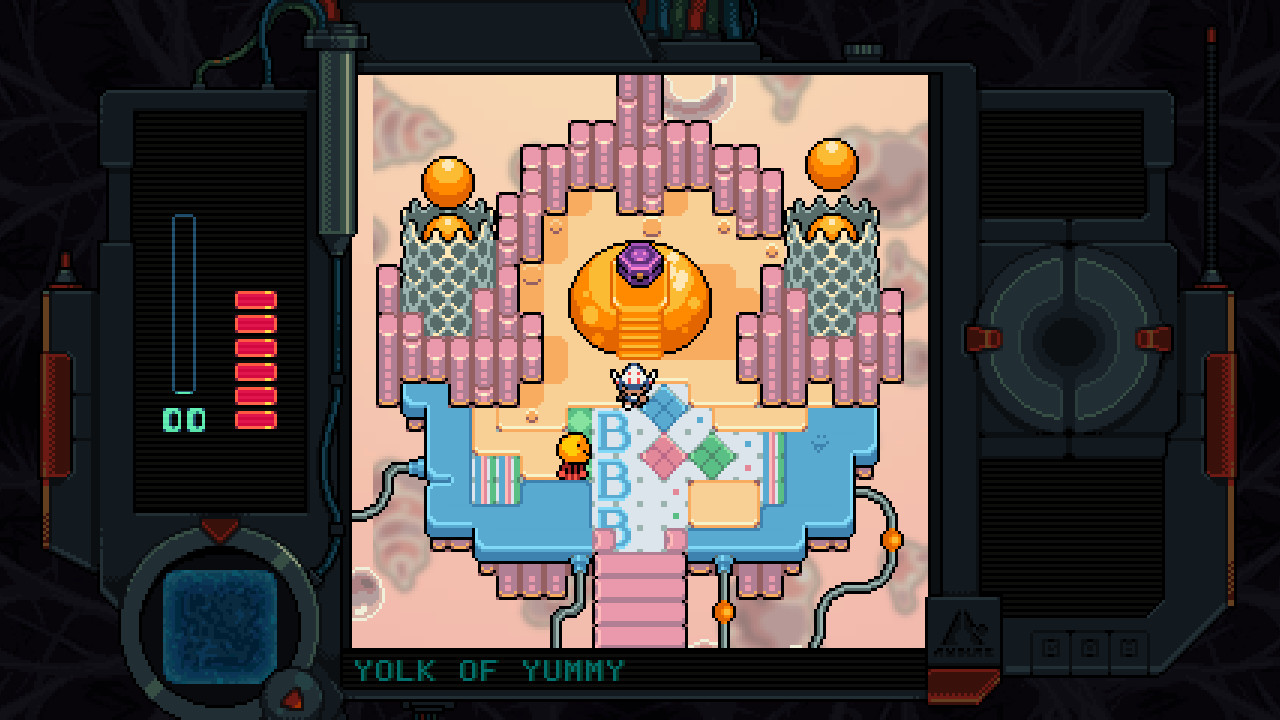

It's OK to be confused, because your character, Nova the Nano Cleaner, is as baffled as you are as she emerges from a giant glowing egg and is told to start cleaning up the town. In her natural 3D state she can run, jump, glide and transform into a car for getting around the larger road-connected areas of the game. But to get her job done, she has the ability to shrink from her natural three-dimensional state down to 'nanoscale', a two-dimensional world that exists within everyone and everything in the strange world of New Theland. These tiny pixel worlds are full of their own people, their temperaments and drives are tied to whatever being they reside in.

While small and pixelated, she explores the 'dungeons' that exist inside of people, solves their puzzles and battles monsters in Psychonauts-esque fashion. As you tackle problems using a vacuum that can move and throw blocks, Nova is figuring out exactly what's wrong with people. Nova's creators say it’s all due to Nano Dust, a corrupting, nigh-invisible evil that needs to be vacuumed up and contained. It's her purpose in life to clean up this mess, so that others might carry out their duties. But perhaps having a 'purpose' isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, and anger and insecurity aren't things that can (or should) simply be swept under the rug.

Not to spoil too much, but Anodyne 2 tells a story of nature versus nurture. Nova is a newborn and only knows what she’s been told—dust bad, cleaning good—and at first that seems to check out. You can shrink down, take away someone's anxiety or self-loathing and they feel better, able to return to what they're meant to be doing. But as she explores further afield and meets more people, she gradually learns nuance. That people are flawed, fragile things and that sometimes their blemishes are what define them, and the world is a strange, often broken place.

What a world it is, too. At a supermarket filled with blurry produce, you'll meet a YouTuber mole who complains they'd rather be covering smaller games, but only the big brands bring in an audience. A swarm of strange worm-creatures paraphrase Charlie Brown as they philosophize over the nature of footballs and failure. A giant crab ponders just how it's meant to sit down on a park bench clearly made for bipedal citizens. It's a rich tapestry of laments—everyone's struggling, one way or another, and it's hard not to root for them.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Long before Nova's story wraps up (around 8-10 hours for most players), Anodyne 2 drives a truck through the fourth wall, as a routine trip back to the game’s central hub city unlocks a meta-commentary layer to the game that runs in parallel with the rest of the story. All the areas you've previously explored are now littered with developer commentary nodes (poke them for semi-in-character insight on the game's design) and collectible coins that encourage you to push at boundaries to reach.

It's not just a game, or a story, or a world, but a thing with human fingerprints all over it

While some coins are on the beaten path, others need you to rudely climb on top of characters to hop over walls and wiggle between polygon seams to get outside of the normal play-space. Breaking the game to collect these coins is rewarded with a store to spend them in, full of early work-in-progress levels (accompanied by even more candid commentary), concept art and even some poetry. Rather than being punished for peeking behind the backstage curtain, I feel like I’ve found the developers waiting there for tea, cake, and a nice chat.

While Nova is interrogating her understanding of her world, you're in a similar dialogue with the developers. The commentary answers big design questions, like why the story-progressing collectibles are found solely in 2D levels at first but also in the 3D worlds later, or smaller questions like 'why is that wall texture all stretched and blurry'.

Anodyne 2—this strange, multi-layered, multi-genre world full of even stranger characters—was made by two people in just a year and a half. Rather than go mad trying to create something perfect, they accepted its flaws, seams and quirks, and want to talk about them with anyone interested in listening. That made Anodyne 2 feel cozy. It's not just a game, or a story, or a world, but a thing with human fingerprints all over it, made by people who want you to know how they did it.

But even if you don’t engage with the meta-commentary, work-in-progress maps, and development diaries, there’s a depth to Anodyne 2's world. Every nanoscale dungeon has cleverly themed puzzles that often mirror their narrative themes. While tackling the concept of Jungian Shadows in one area, you have to solve puzzles alongside your own mirrored shadow-self on the other side of the screen. Another character wracked with anger has an inner world made of throbbing meat and fire-spitting monsters constantly in conflict with each other. Grief and frustration radiate through brief text boxes and chunky little sprites, but you’re seldom far from some absurd humour, saving it from getting too heavy.

It's also very accessible. While I didn’t need it, anyone who wants to can halve damage taken, turn invulnerable or even access a handily spoiler-tagged walkthrough in-game. It's clear that they want as few barriers as possible between the player and whatever experience they want to have in this angular, blocky playground, whether you're caught up in Nova’s personal struggle or just how the sausage is made.

Since I'm hoping you’ll take the plunge and try it yourself, I've omitted a few (OK, a lot) of the more strange and surprising moments of the game. Anodyne 2 does a lot with its limited budget of polygons, pixels, time, and money. Sometimes you don’t need to be the biggest or the best, just earnest and true to yourself.

The product of a wasted youth, wasted prime and getting into wasted middle age, Dominic Tarason is a freelance writer, occasional indie PR guy and professional techno-hermit seen in many strange corners of the internet and seldom in reality. Based deep in the Welsh hinterlands where no food delivery dares to go, videogames provide a gritty, realistic escape from the idyllic views and fresh country air. If you're looking for something new and potentially very weird to play, feel free to poke him on Bluesky. He's almost sociable, most of the time.