Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

Weird Weekend is our regular Saturday column where we celebrate PC gaming oddities: peculiar games, strange bits of trivia, forgotten history. Pop back every weekend to find out what Jeremy, Josh and Rick have become obsessed with this time, whether it's the canon height of Thief's Garrett or that time someone in the Vatican pirated Football Manager.

There's a good chance you haven't heard of The Wheel of Time. No, not the beloved series of fantasy novels penned by Robert Jordan, or the less beloved but still pretty good TV show cancelled by Amazon, or the recently announced and preposterously ambitious RPG. I am of course referring to the other Wheel of Time, the first-person spell-slinger developed by Legend Entertainment and released in 1999.

The Wheel of Time was praised by critics when it launched, partly due to its association with the popular series of fantasy novels, but equally due to its decent singleplayer campaign and innovative multiplayer mode. Despite this, it sold poorly, fading quickly amid the torrent of first-person shooters that rushed across shelves in the late nineties.

But if The Wheel of Time has slipped from your memory, it'll stick like a Heron-marked blade in a Trolloc's chest once you hear the tale of how it was made. Even in the notoriously difficult world of game development, where projects shift and change more often than the dreamscapes of Tel'aran'rhiod, the story of The Wheel of Time is a wild ride.

Indeed, the reason it exists at all is largely down to the determination of one man. Glen Dahlgren is a game developer and, in more recent years, novelist, whose other projects include Unreal 2: The Awakening and Star Trek: Online. But The Wheel of Time remains his favourite, despite the fact that guiding it from conception to birth seems, from the outside, like a five-year long ordeal. "The fact that we shipped anything at all is kind of a miracle," Dahlgren tells me halfway through our chat. "My old boss at Legend used to say every game you ship is a miracle, and I didn't really understand that until this game."

New Spring

The story of The Wheel of Time's creation is convoluted to say the least, and Dahlgren gives his own intricate account of it on his website that's well worth reading. But it starts with a concept that Dahlgren dreamed up after Legend released the 1994 adventure game Death Gate, one which had nothing to do with The Wheel of Time.

His idea was for a fantasy, multiplayer FPS that combined the fast-paced action of Doom with the move/counter-move play of Magic: The Gathering, along with roleplaying elements from the boardgame WizWar. The result would have been a four-way mixture of combat and espionage, straddling the line between a fantasy MMO and something vaguely reminiscent of the Half-Life mod Science and Industry.

Players would control networks of spies from their own customisable fortresses, and engage in complex, reactive spell-based combat. "I'm choosing to do something to you, and you can do something about that if you want … and the more powerful it is, the slower it's going to be," Dahlgren says. "I love the idea that it was a strategic choice, not a tactical choice … the interplay of those offensive and defensive artifacts [was] really fun."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The idea stretched far beyond Legend's experience making low-budget adventure games, seemingly doomed to obscurity following Legend's acquisition by the publishing giant Random House, which wanted to exploit Legend's particular talents for its own suite of books licenses. Unsatisfied with the licenses offered to him by the publisher, Dahlgren made a curious gambit. He suggested that Legend make a game based on The Wheel of Time by Robert Jordan—an author who had no existing relationship with Random House.

"I really wanted to play with that world," Dahlgren says. More than that, he wanted to ensure the videogame rights for The Wheel of Time ended up in safe hands. "I wanted to save him from Byron Preiss, because that was the other organisation that was after his license, and they made horrible games," Dahlgren says.

Dahlgren was happy to abandon his multiplayer concept and continue making adventure games provided the stories excited him. Since Dahlgren's idea gave Random House an excuse to approach Robert Jordan and possibly convince him to sign a book deal with them, the publisher agreed.

The Great Hunt

Reenergised, Dahlgren wrote a design doc for an adventure game set in The Wheel of Time—one that took place in a 3D world, featured real-time puzzles, and included an inventive real-time with pause combat system that let players select blade techniques (known as sword-forms) from a list. Dahlgren sent this to Jordan, elaborating upon the design while waiting for Jordan to reply.

Jordan did reply, but it was less than enthusiastic. Desperate to salvage the idea, Dahlgren flew out to meet Jordan along with Legend's then-president Bob Bates. Together, they had what Dahlgren believed was a jovial, productive meeting. "He showed us around his house. There were weapons in places, which was really cool. I got to ask him where he likes to work, and he said he does his thinking all over the house," he says.

Dahlgren returned to work feeling confident the project was saved. Then he received what he calls "The Fax of Doom". This reiterated all of Jordan's original concerns in even more definitive fashion, seemingly putting an end to the whole project.

According to Dahlgren, Jordan's doubts centred around a general reservation about the marketability of adventure games. "He understood the limitations of the genre," Dahlgren says. "The genre itself was not doing very well. It was on its way out, and he didn't want a game that didn't have a chance to be big."

But there was a lifeline. During the meeting at Jordan's house, Dahlgren had wheeled out an alternative game concept that he'd cobbled together on the flight to meet the author, one that took place in a parallel dimension to The Wheel of Time. "One of the ways I convinced Jordan that I can make this game is 'I'm not going to stomp on his storyline. I'm not going to kill his main character,'" he says.

Jordan expressed interest in this concept, but there wasn't much else to it. In a mixture of inspiration and desperation, Dahlgren retrofitted his idea for the Doom/Magic/Wizwar FPS onto this concept, with players assuming the roles of various Wheel of Time factions which attempt to steal the magical seals which keep The Dark One (the story's godlike villain) at bay.

The Gathering Storm

Dahlgren drew up a design document and an accompanying experience document, and sent them off to Jordan, who approved it. Random House, however, did not, and as part of a growing ambivalence toward gaming in general, pulled its financial support for Legend (while keeping its stake in the company).

Now, Dahlgren had the go ahead from Jordan, but no publisher to fund the game he had just received the nod to make. On top of that, Dahlgren also had no technology to make the game. To solve this problem, he hired an eclectic team of artists, architects and character designers to create detailed concept art and went pitching.

Eventually, the team secured the interest of Epic Games. Mark Rein, Epic's Vice President, was receptive, and following a meeting with Rein and Tim Sweeney, Dahlgren received a copy of Unreal engine and its level editor to mock up a prototype. Dahlgren produced this himself, then showed them to Epic.

According to Dahlgren, these prototypes are what convinced Tim Sweeney of the potential of licensing Unreal Engine to third-party developers. It also provided Dahlgren with the opportunity to do something he'd wanted from the start—to shift Legend from being a developer of niche adventure games to a creator of blockbuster first-person shooters.

"What I wanted to be was a version of Raven [Software]," he says. "We would be that for Epic. We would be the one to come in and say 'Listen, we can make something different than what you're making, something that has a different soul … even though it's using your technology.'" This is also why Dahlgren didn't do what seems so obvious today—make a Wheel of Time CRPG. "Everybody asked me 'Why don't you just do an RPG?'" he says. "That's not what I wanted to do. What I wanted to do was a first-person shooter."

Among all this, Legend also wrangled a new publisher—GT Interactive. Finally, everything was in place to begin making the game Dahlgren had dreamed of. There was just one small problem. The deal Legend signed didn't come anywhere near to footing the bill for the game Dahlgren had envisioned.

The Dragon Reborn

Undeterred, Legend set about building a prototype of its magical multiplayer espionage game for GT Interactive. Through developing this prototype, Dahlgren and The Wheel of Time team realised two things. First, the grand, complex multiplayer experience they had envisioned needed drastically reducing in scope. Second, the prototype itself made for a surprisingly engaging singleplayer adventure.

With this new perspective, and after struggling repeatedly to meet its development milestones for the original vision, Legend opted to redesign The Wheel of Time. This new design stripped out all the espionage and persistent, MMO-like elements from the multiplayer, narrowing the scope to just the customisable citadels and the counter-based magical combat. This multiplayer would be accompanied by a more traditional linear FPS campaign, one with its own Wheel of Time story.

For this new story, Dahlgren abandoned the parallel universe concept and made The Wheel of Time a prequel to Jordan's novels, allowing for a story that better fit the new structure while upholding Dahlgren's assurance to Jordan that he wouldn't mess with the main narrative of the books (years later, Jordan would write his own Wheel of Time prequel—New Spring). The story would revolve around the four playable factions in the multiplayer—The Aes Sedai, the Children of the Light, the Forsaken, and the dark forces within the abandoned city of Shadar Logoth.

The story would also take players through environments based upon the four citadels in the multiplayer, like Shadar Logoth and the White Tower, allowing Legend to build the singleplayer using the multiplayer's assets. "Choosing those four factions is what drove most of the environments out of the gate, because I needed their home bases," Dahlgren says. The central plot came to Dahlgren on a flight to Italy to visit his then-girlfriend. "I couldn't write it down because I had no piece of paper, I had no pen. So I had to sit there for, I think it was four hours, and just to repeat it over and over."

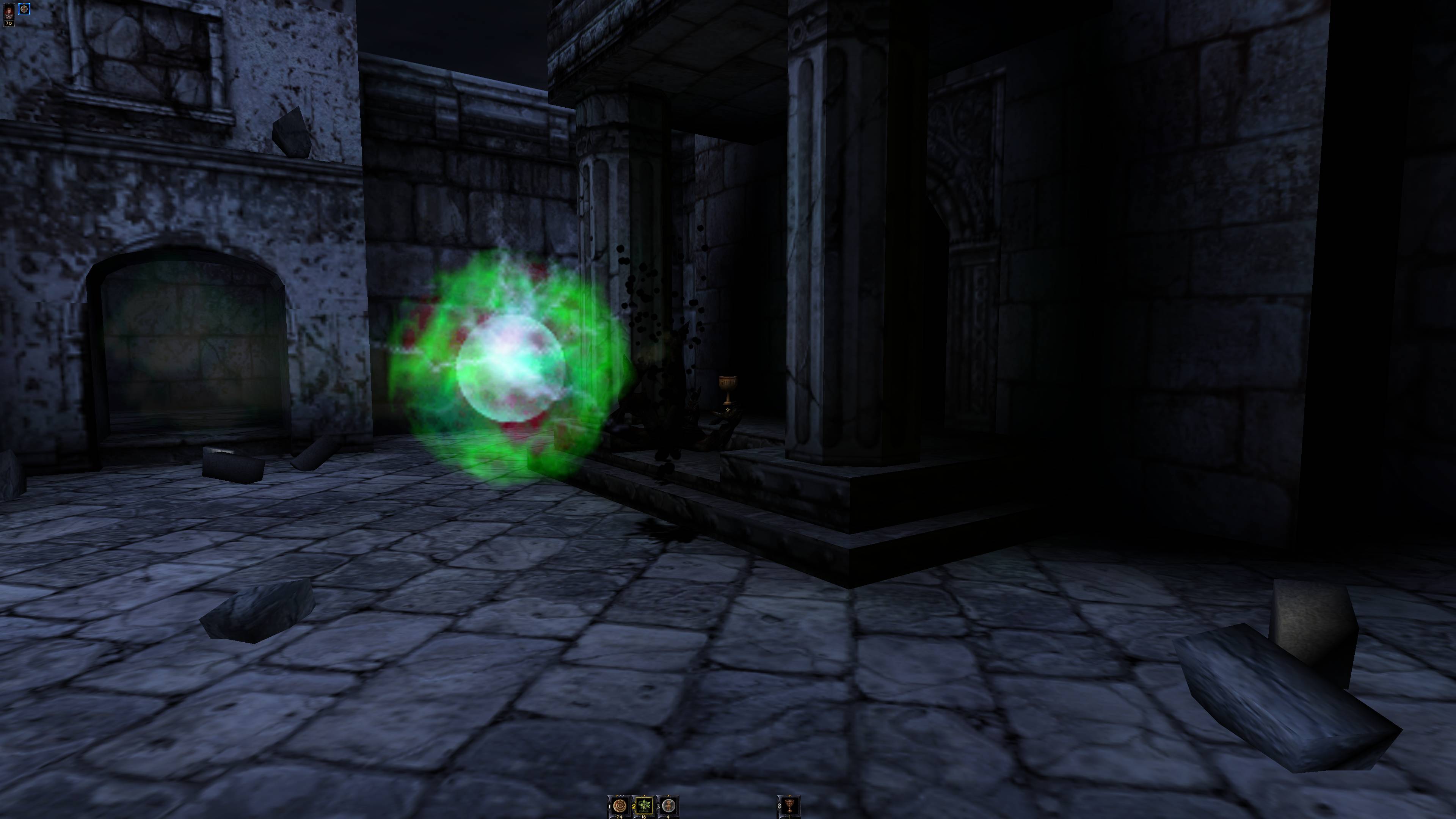

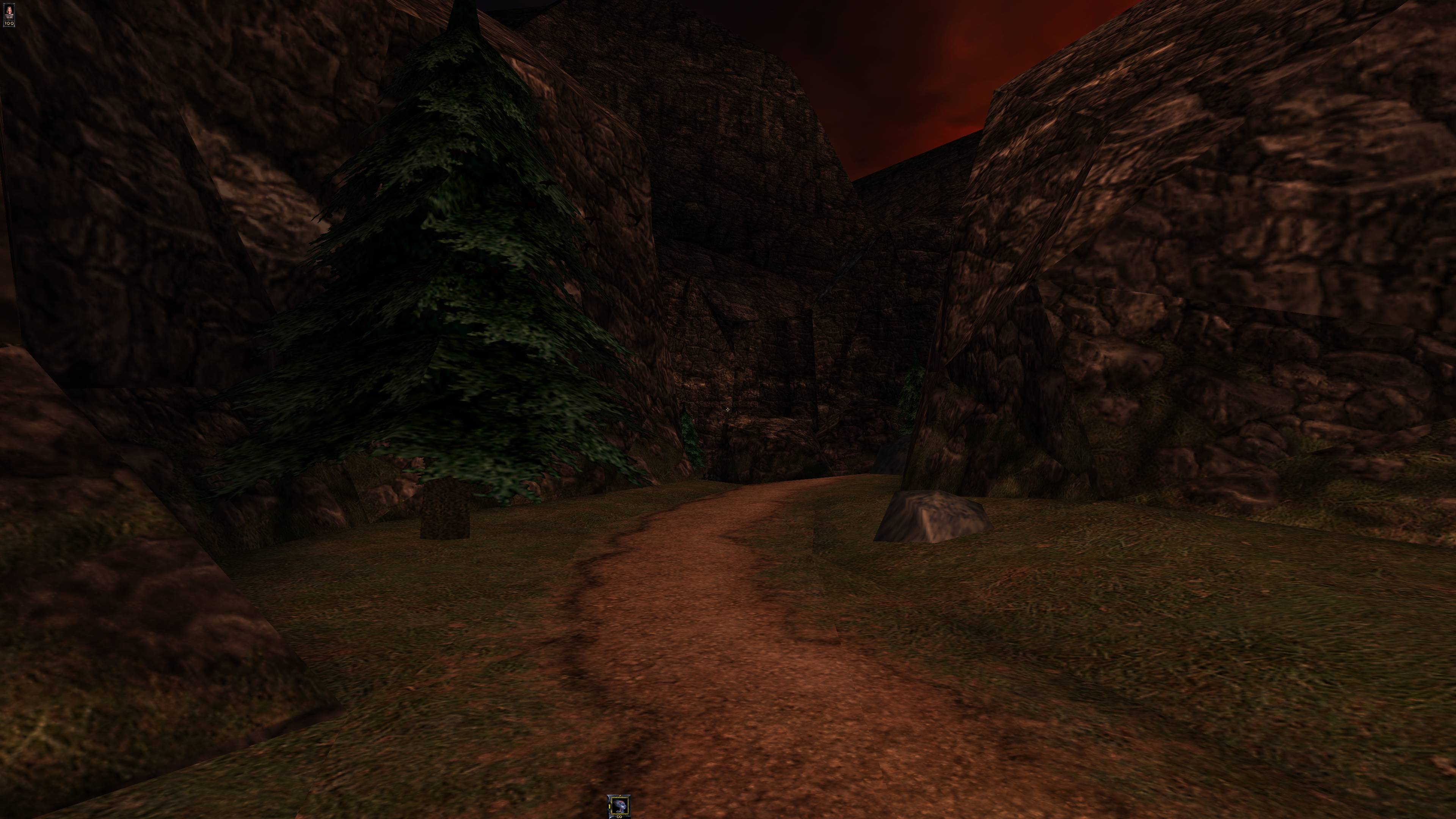

Making some of these environments fun to play in proved a significant challenge. In the books, Shadar Logoth is an abandoned, cursed city, with no corporeal enemies to fight. So Legend had to come up with threats and obstacles that felt appropriate for the setting, like a strange mist that attacks the player, and dark tendrils that writhe out and block your path. Dahlgren believes these environments at least partly inspired the look of Shadar Logoth in the recent Wheel of Time TV series. "I think that the TV show guys absolutely played our game," he says."

Building the White Tower, meanwhile, was all about trying to provide a sense of scale and detail that evoked the high fantasy setting of the novels. "I want[ed] to bring a piece of fantasy fine art to life," Dahlgren says. "I don't think anything in the game was the kind of scale that you would see nowadays … [but] they're architecturally beautiful. The textures are amazing."

Lord of Chaos

By this point, Dahlgren had been working on the project for around four years. With a year to go until launch, Legend had only just put together a team capable of making it. It was at this point Dahlgren was called into a meeting with Legend co-founder Mike Verdu and producer Mark Poesch, who told Dahlgren they planned to cut the singleplayer entirely. "'We are gonna trash this down to the bare bones'", Dahlgren recalls. "'We need to release something, it's gonna be a multiplayer game, and that's all it's gonna be'".

Dahlgren, desperate to save the story, begged for a chance to revise the scope one more time, and see what he could trim from the whole package to rescue the single-player. Verdu consented, and Mike went back and began cutting yet more spokes off The Wheel of Time.

Levels and ideas were cut. The multiplayer was slimmed from teams to four players working as individuals, and the interactive NPCs Dahlgren had intended to convey the narrative were replaced by straightforward cutscenes. "That became the game that we shipped," Dahlgren says.

Even when The Wheel of Time was done, it wasn't. Dahlgren wasn't present for the game's official launch date, as he was getting married in Italy. Yet when he returned from honeymoon, he discovered the game hadn't shipped after all, while in his absence Legend had put together a demo that Dahlgren says "made no sense".

"It had no story structure. It had nothing. So I had to just dive in and try to get that demo back on track," Dahlgren says. "I'm like 'this is what happens when I leave'".

A Memory of Light

The Wheel of Time released on November 9, 1999. Critically it was well received, scoring 90% in PC Gamer US. Commercially, though, it was a flop. Dahlgren puts this down to several factors, such as the marketing. "GT was going under, and they only had so much marketing money to throw at it, and they threw it at Unreal Tournament," Dahlgren says. "I don't even know if we were placed on the right section of the Best Buy shelves at the time, which sucks."

But he also believes that the counter-based spell system inspired by Magic: The Gathering demanded too much learning from players at the time. "It might have been one of the things that made the game less accessible than I would have liked," he says. "There were so many ter'angreal (the magical items players used to cast spells) that it became hard to mentally map what you needed to do to react to the right thing."

Nonetheless, The Wheel of Time proved influential in other ways. As it was developed concurrently with Unreal, certain tech and design ideas fed into both Epic's debut shooter and the engine which supported it. "We made our own particle system. They didn't have a particle system at the time. We worked to create AI that they had never seen before," Dahlgren says.

Even Unreal's level design appears to have been influenced by Legend's work on The Wheel of Time. "They were standard levels [for] the time," he says. "Rather than a full on place that you could explore. As soon as we showed them some of the stuff that we had produced as concept sheets, Tim said 'I can't believe this is my engine.' Then, suddenly, in Unreal you see a lot of half timber buildings. So I think we absolutely influenced them."

And while it wasn't a smash hit, The Wheel of Time's multiplayer did find a core community of players who appreciated its ambition, even in its stripped-down form. "Once the muscle memory was there, people loved it. They loved the idea of bouncing back attacks against each other, or putting on a fire shield before you walk through a bunch of landmines somebody had placed." Dahlgren says. "I never played my games after they were done, but this one I played forever because it was so fun."

The Wheel of Time also sowed the seeds for Dahlgren's emerging career as a fantasy novelist. His first novel, The Child of Chaos, derived from an alternative, Wheel-of-Time-less story concept he used in a pitch to Activision while searching for a new publisher for the game, as Activision wasn't interested in the Wheel of Time licence. His most recent novel, The Realm of Gods, won numerous awards, including the Dante Rossetti Grand Prize for young adult fiction.

And what did Jordan himself think of Legend's game? In the latter stages of development Dahlgren reconvened with Jordan to show him what Legend had spent so many years working on. As Dahlgren guided Jordan through the game's opening section, he was nervous.

"As we were walking around, he didn't say anything," Dahlgren says. "And then he said. 'Yes, this is beautiful.'"

Rick has been fascinated by PC gaming since he was seven years old, when he used to sneak into his dad's home office for covert sessions of Doom. He grew up on a diet of similarly unsuitable games, with favourites including Quake, Thief, Half-Life and Deus Ex. Between 2013 and 2022, Rick was games editor of Custom PC magazine and associated website bit-tech.net. But he's always kept one foot in freelance games journalism, writing for publications like Edge, Eurogamer, the Guardian and, naturally, PC Gamer. While he'll play anything that can be controlled with a keyboard and mouse, he has a particular passion for first-person shooters and immersive sims.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.