The best and worst in-game books and codexes

Read any good games lately?

Literature’s had a pretty good run, much of it without any fancy graphics and animations and particle effects to bolster the words. Games love text too. Text is cheap. You can paint a picture of galactic chaos or epic history in about the same time it takes to type ‘and then something cool happened’, without having to spend the next week designing armour and creating 3D characters to act it out. Yet despite centuries of practice, most games still haven’t worked out how to present all this (which let’s face it, is often there more for the writers’ satisfaction than our actual enjoyment) in a punchy, satisfying way. What works? What doesn’t? Let’s take a quick look at some of the ways games have handled books, letters, codexes and more.

Deus Ex: Human Revolution

Even when you don’t affect a world that much, it’s nice when it pretends. News stories are one of the best and cheapest ways to both highlight your achievements, and reframe them in interesting ways, from acts of heroism to outright terrorism. Human Revolution wrapped them in one of the sleekest packages for this—the Picus Daily Standard. At once a chance to see what was taking place out of your sphere, and see the effect of your adventures on the world. While even a few years later, the futuristic look feels distinctly retro compared to iPad news apps, to say nothing of whatever direct-brain interfaces we’ll likely have by the time of Deus Ex’s dark not-too-distant-future, Picus keeps it pretty, keeps it punchy, and above all, keeps it brief.

Deus Ex: Mankind Divided

Ah, but when it comes to eBooks, things aren’t so smooth. Look at this. Even the original Kindle would wince at these datapad layouts, complete with non-slidable panels, slow refresh rate, poor quality fonts and typography, and non-consistent use of glows. Sure, it’s readable, but it’s hard to imagine anyone wanting to, even before factoring in that in the wasteful future of Deus Ex you apparently need a new device for every Wikipedia entry. The crappy quality of this design only stands out more amongst Mankind Divided’s otherwise superbly rendered future, where everything you encounter seems to have emerged fully formed from the brain of a maverick product genius. This, meanwhile, feels like a first attempt at customising Twine.

Fallout 4

In the not-too-distant future, who needs books? We’ll have computers! Specifically, ghastly green teletype machines that would be tolerable for simple acts like opening doors, but could be much more of a nightmare if the cast of Five Nights At Freddy’s occasionally popped up for a jump-scare. The horrible font. The clackering of the text. The endless pages that try their best to tell stories of post-apocalyptic horror, despite being locked in an interface that would make even a hardened wasteland explorer decide that whatever happened probably doesn’t matter that much. Even accounting for the 50s vibe of the rest of the game, these are hideous technological throwbacks that knife their own storytelling in the back. The closest they come to being appropriate to the setting is that in using them, the living definitely envy the dead.

Skyrim / Ultima

What’s an RPG shelf without a few strangely short books that probably don’t need hundreds of pages and a stiff leather jacket? While RPGs have always been wise enough to realise that most players will accept this deviation from reality, it’s still interesting to look at the differences between these two great franchises. Skyrim for instance clearly assumes that all of Tamriel’s readers are half-blind—or possibly playing on a television screen—leading to very slow-paced tales on glorified flashcards. Ultima meanwhile wanted you to squint. But at least Ultima had the advantage that unless a book was specifically screaming ‘crucial plot element’, it was most likely to be flavour, sparing you tediously flicking through shelves in the hope of finding a boost to one of your skills. At least both franchises keep their tongues firmly in their cheeks, whether it’s The Elder Scrolls’ obsession with the Lusty Argonian Mage, or Ultima’s fine line of joke books, occasional explosive booby-trap pranks, and the revelation that wise Lord British, founder of Britannia’s favourite story is “Hubert the Lion”. Can’t sleep without it, apparently...

Mass Effect

A controversial one here, perhaps, but Mass Effect is one of the games where the built-in Codex arguably makes the world less enjoyable. The game does a fantastic job of introducing everything that’s actually important without relying on it as a crutch, with the dry writing and endless unlockable pages of SF guff coming across as homework rather than a gripping read. Do we really need to know, for example, the origins of every last whiffle-bolt supplier on the Citadel? No. It’s just not that important. Save it for the design bible and tie-in books.

While there are a few interesting flourishes, including Codex entries based on what the universe thinks rather than necessarily the actual truth, the Hitch-Hiker’s Guide To The Galaxy it is not. And ironically, it shows the difference itself, in the form of Mass Effect 2’s fantastic Shadow Broker DLC and the unlockable files within, which actually do give you a chance to peer at your party’s dirty little secrets. Jack’s secret love of poetry. Miranda’s online dating life. Tali’s repeated installation of a suit tool called ‘Nerve Stim Pro’. Oh, the blackmail opportunities...

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

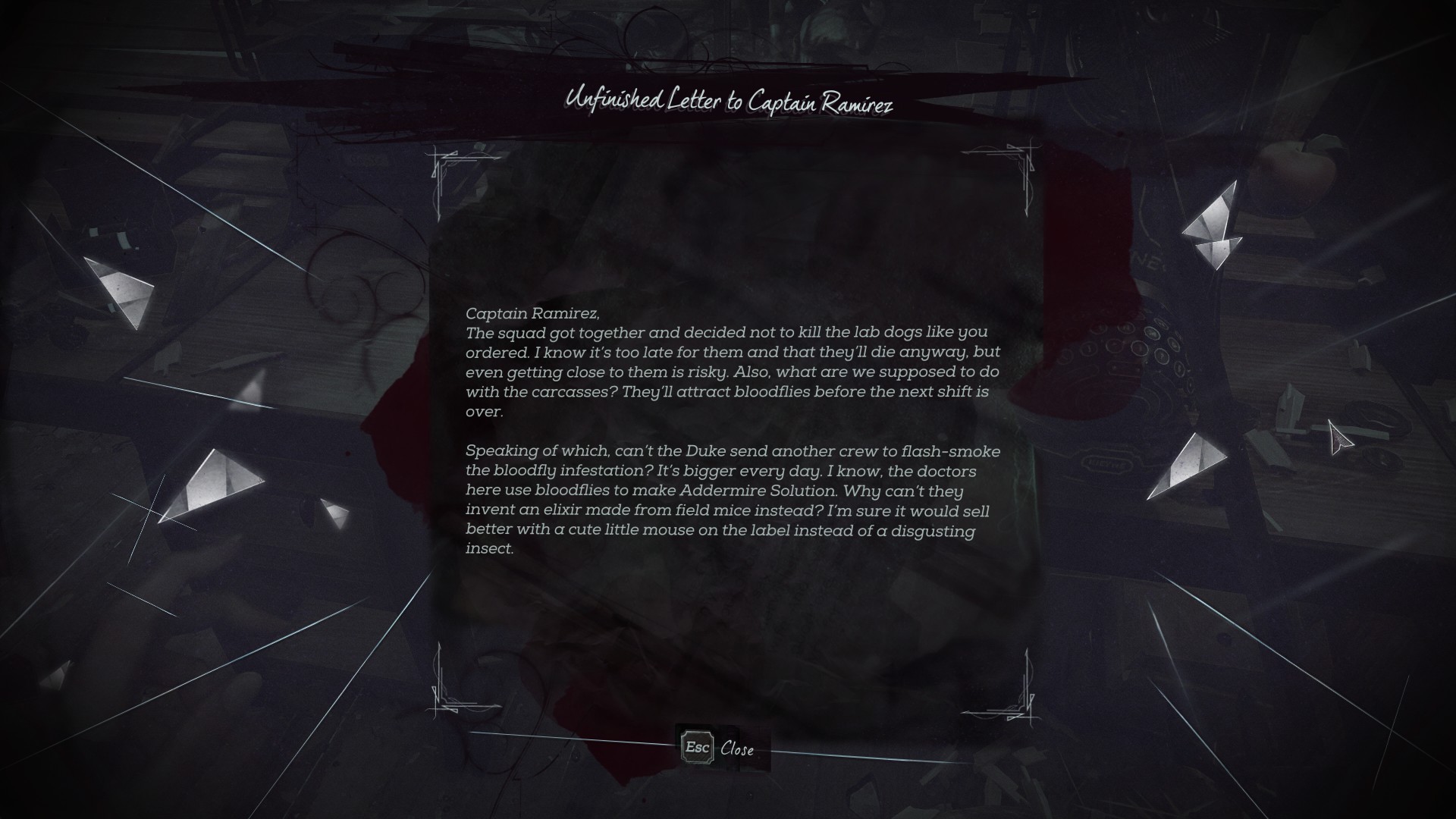

Dishonored 2

Dishonored is a great example of how just a little thing can really annoy. Its text isn’t difficult to read, the font is pretty well chosen, if not exactly conveying the sense of a written document in the same way as many other games with this level of texture and detail, but does it really have to sway back and forth while you’re reading? There’s a time for ambient animation to breathe life into a scene, and a time to make the player feel slightly sea-sick. No. Scratch that. True for the first, not so much for the second. Swish… swish… it’s an effect applied to all the menus and other data screens and really contributes to making reading the lore an unpleasant experience. A shame, because that lore is actually interesting. Dunwall and Karnaca are two of gaming’s best cities, and their depth and backstory is fascinating. If you can stand to actually read it.

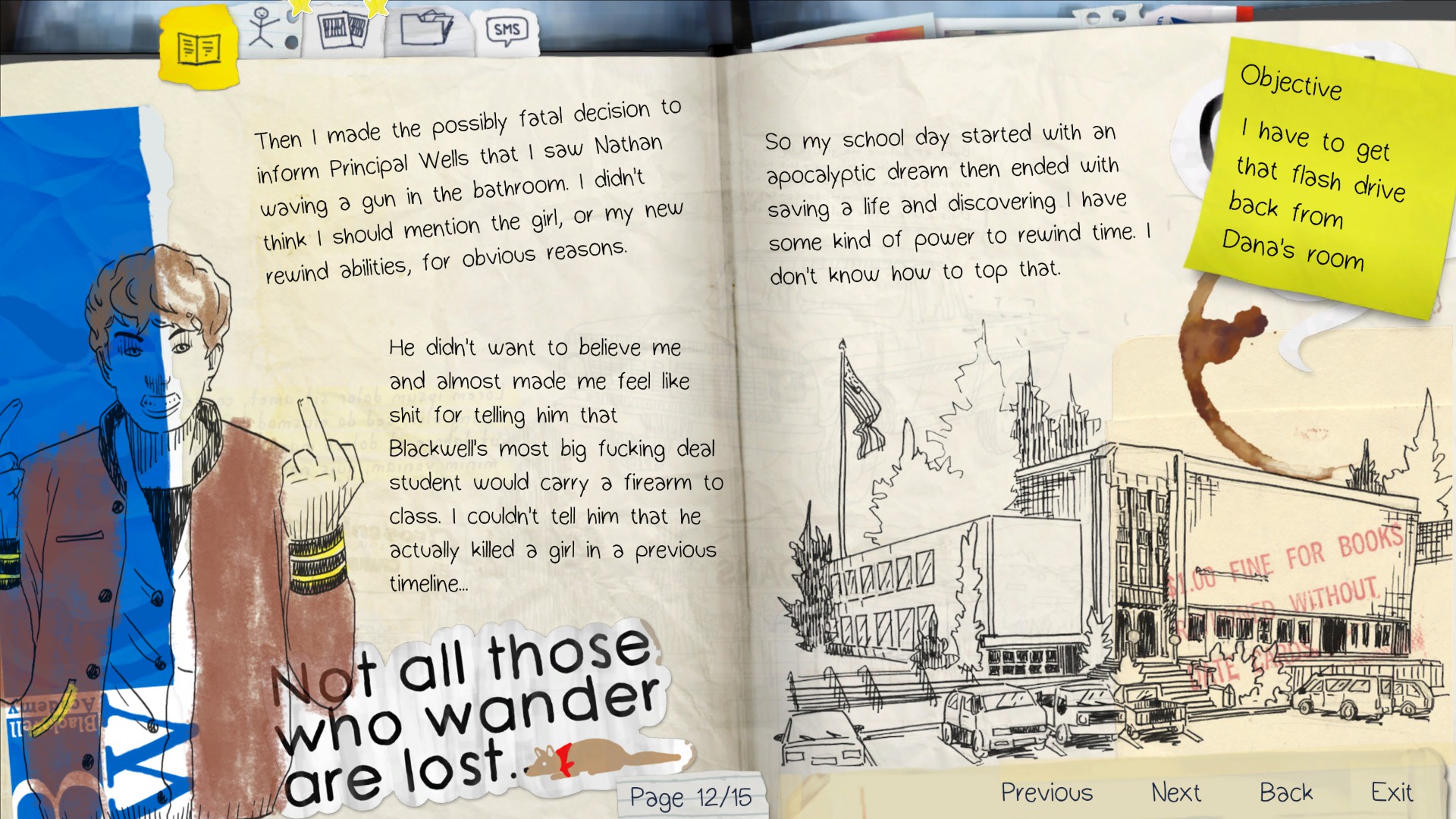

The Longest Journey and Life Is Strange

I'm bundling these together because they do the same basic concept—the primary text in the game is our main character’s diary. This serves several purposes, including offering a potted version of the story if you dip away for a while and forget things, but most importantly giving us a direct look inside their head. It’s a technique that only works if you actually like the main character, but fortunately that’s not a problem for either series and its charismatic leading ladies. In particular, it’s a way of bridging the gap between our perception of the game, as an untouchable god-figure, and theirs, as someone for whom all these moral decisions are actual life-changing events. Simply seeing the game from that perspective is enough to make everything carry that much more weight, and it doesn’t hurt that they’re fun reads too.

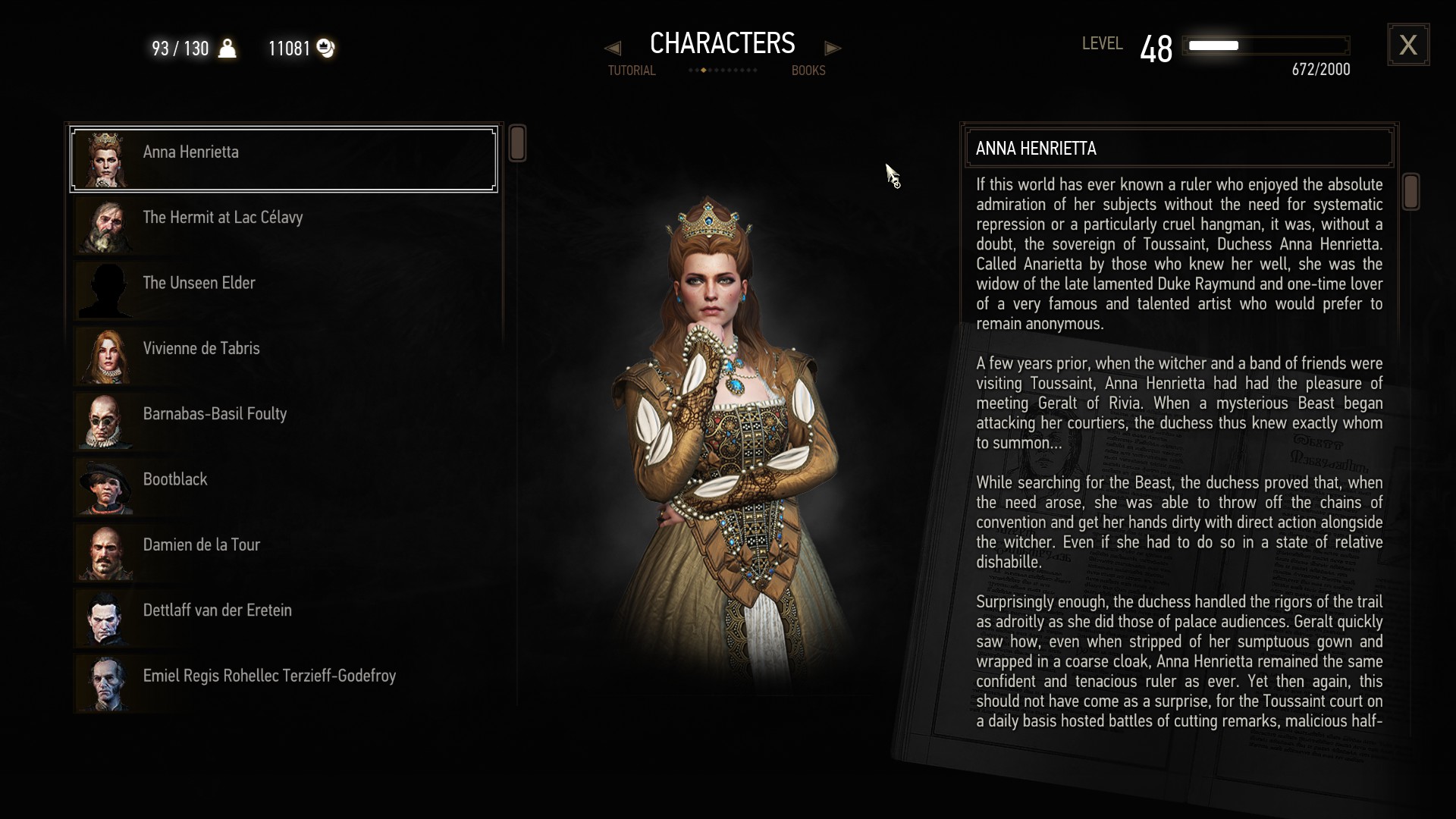

The Witcher 3

What separates The Witcher from most in-game codexes is its sense of character, with everything being described from the perspective of in-game poet, lover and occasional sidekick Dandelion. The nature of the game also rewarded taking the time to dip into the Codex, given that for a travelling monster-slayer, knowledge is power, and never took away from the fact that while us as players might not know our drowners from our necrophages, Geralt himself was always able to be a reliable source of information and provide the condensed version.

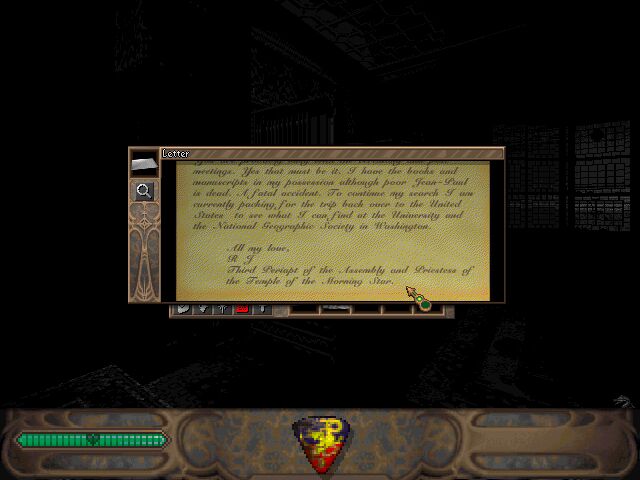

Realms of the Haunting

Here’s a retro classic, sadly not helped by the low-resolutions of the mid-90s. Nothing damages the mood of an otherwise well-made document like peering at it through a letter-box and finding it more poorly compressed than an old JPEG from a lost Geocities page. It’s not quite as bad blown up to full screen though, and even with its technical problems, it demonstrated how to write documents that actually fit the world and contributed to the lore without feeling like extracts from the design bible. Most took the form of letters between the characters, their identities not always immediately obvious, and turning the relatively simple battle between good and evil at the heart of the story into an epic tale of Faustian deals, ancient cults, doomed love, and a deep mythology stretching between multiple worlds. The visual look certainly didn’t hurt, with everything presented as aged pages, hand-drawn maps and messily scrawled journals. And if you didn’t like them, you got to burn several of them as part of a puzzle. Splendid.

The Neverhood

Of course, if you really, really want to make sure nobody misses your game’s lore, there’s always the Hall of Records—aka The Place Where Basically All The Game’s Backstory Is, as carved onto the walls of a corridor that takes about five minutes to trudge through even if you ignore all of the words. Oh, and when you get to the other end? You have to walk back, obviously. You know it’s good stuff when even a game’s own wiki states, and we quote, “it is suggested by most not to read all of it.” Truly great literature. Who could ask for anything less?

But of course, these are just a few cases. Which games have convinced you to pause saving the world to flick through a good book, and when has that background just been so much blah? It’s fun to get lost in backstory, just as long as the writers aren’t too obsessed with their own lore.