Kings of comedy: the art of interactive humour

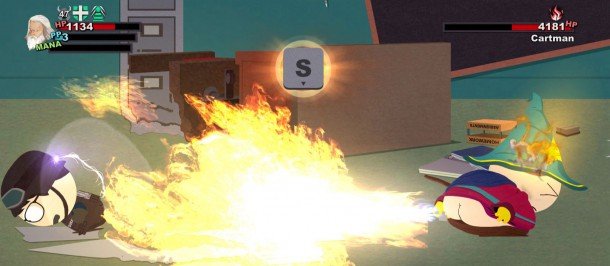

The Stick of Truth “was an excellent crash course in the problems of timing as exposed to the player,” he says. “A lot of the best jokes in South Park were hard-won because they were our attempt to anticipate what the player might do and respond only if they chose to take that action, and that's the stuff I'm the proudest of because that's the stuff that's hardest to do well. You can make someone laugh in a cutscene trivially—that has been around for thousands of years. But to get them to be in on the joke, and not just that, but be the person who has the best line, so to speak, there's very little precedent for it. There was experimentation in adventure games, and then a long drought, and finally we're coming back here and there.”

The direct involvement of the player in the comedy is an idea that still feels relatively untapped, but it's one that Necrophone Games' terrific Jazzpunk manages to exploit. Many of its jokes rely on the element of surprise, often subverting the player's expectations, or simply offering an unexpected result to a simple interaction. Attempting to speak to a man on a bridge, for example, causes him to jump off, emitting a Wilhelm scream as he falls. Reaching out to manipulate the hands on a clock reveals your arm to be a wooden prop. What makes it so consistently funny is that you're never sure what the results of your interactions will be, and that only encourages you to explore and discover the surprises for yourself.

“It was very important to have that possibility space,” Luis Hernandez says. “The open world aspect ties into that—the fact that players are missing things and a joke doesn't really work if you see it coming. A lot of games are structured around a core mechanic, and even in comedy I feel that's the wrong approach.”

“The kind of comedy we're doing is more like punchlines,” adds Jess Brouse, likening the game's humour to a jack-in-the-box. “It's that kind of sharp 'I got ya' surprise that pops out at the end.”

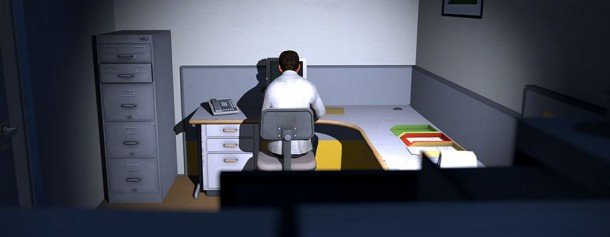

Every bit as surprising is the revelation that Jazzpunk didn't begin life as a comedy, and only developed into one as Hernandez and Brouse began to add Easter eggs into their spy fiction while they were building it to amuse themselves. Slowly, they began to consider how comedy could be used as a central game mechanic, and Hernandez began studying other games in order to better understand how to make their own work better. “Looking at how other games at the time were being built, like shooters and puzzle games, I realised that a lot of games are structured around some kind of resistive element,” he explains. “Most games are built with a start and end state, and they throw in a bunch of stuff along the way so you can't just walk to the end of the game. In most games that's guys that shoot at you or something that shoots at you. And in other games it will be puzzles that impede you, and you have to walk around and find coloured blocks or keys and fit them into doors.”

Hernandez's boredom and general dissatisfaction with these two base types of resistance helped to shape Jazzpunk's development. “I realised that some of this comedy stuff we were gradually adding to the game could actually function as a kind of resistive element. Even if it was something passive that players could walk past, you'd still have curious players that would seek out this material. So while our game has some simple puzzle elements, they're mostly very straightforward. And rather than shooting or outright puzzle solving, comedy became the resistive element.”

If the secret of Jazzpunk's success is that element of surprise, its comedy is still very much scripted, and yet most players would probably admit that the biggest laughs they've experienced in a game have emerged from entirely unplanned moments of comedy. In some cases—like the aforementioned Octodad or even its spiritual precursor, Bennett Foddy's hilarious QWOP—the games are purposely designed to result in moments of physical slapstick, but is giving players the tools to create their own comedy moments a valid approach to making funny games? “Short answer—yes,” says Erik Wolpaw, before wryly adding “long answer—Chet [Faliszek, Wolpaw's co-writer on the Portal games] and I are out of work if comedy writing gets replaced by tools programming. So while I admit it's entirely possible and truly effective, I'm against it.”

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Indeed, often the moments that provoke the most laughter come from the most unexpected sources, sandbox games often proving a rich source of humour. “Battlefield does make me laugh a lot,” admits Graham Linehan. “The things that can happen in Battlefield are obviously unscripted but maybe that's why it's funny. Maybe that feeds into [the idea of] emergent gameplay lending itself to comic timing—like when you wander into a building and throw a few grenades and the building suddenly collapses onto you. It's unexpected. It fulfils a lot of the rules of comedy, you know, it's a mixture of the surprising and the inevitable.”

The common link, it seems, between systemic comedy and scripted comedy is that they're both at their best when subverting expectations. Linehan agrees that a degree of spontaneity is as welcome as a dose of wit. “Maybe what all these games have in common is that they're playing the player—they're messing with your expectations more. In that respect, I always think there's been a link between horror and comedy. Like in Silent Hill, where you have that toilet door that's closed, and you knock at it three times and there's a pause and then knock knock knock from the other side. It's terrifying, but it's very funny. The best comedy is really where you're being played to some extent.”

Could the likes of Portal, Jazzpunk and The Stick of Truth bring about a comedy revival, or are we a little way off from audiences actively seeking out comedy games? “I like a bit of intelligence, I like a reference that seems neat and clever and takes me by surprise,” says Linehan. “I value wit over comedy [in games], I guess. Valve are really good at it, and I always think something like Left 4 Dead is very witty in how it's constructed. But when I need a good laugh, will I watch The Producers or play a videogame?”

Hernandez believes that more people might begin to develop a taste for comedy if more games attempt to make players laugh. “I haven't played it yet, but The Stanley Parable, Goat Simulator, games like that – if they come out and start building up a Blockbuster shelf of comedy that people can see every time they go to the Steam Store then it could happen.

“I think people go into games to be amused,” he continues. “I don't think receiving comedy as a reward is really any better or worse than receiving points for stepping on people or killing-spree notifications for shooting people in the face. Essentially, people play games a lot of the time to get an endorphin release in their brain, so whether that's a joke or solving a puzzle [I] don't think there's that much of a disparity between the two.”

Brouse suggests that if interactive comedy is to take off, it will take time to manifest, while Hernandez believes that it's too soon to judge whether or not their game has influenced other developers to follow their lead. “We won't know if they took it to heart yet,” he says. “I keep imagining a student in, say Japan, and that Jazzpunk is close to what they want to make. I mean, I've met people who say that Jazzpunk is something close to what they're looking for in games. There's definitely a huge audience looking for things other than shooting and puzzles, and for them Jazzpunk scratched an itch that perhaps they didn't know they had.”