AI is listening: Omnipresent robo-moderators are the latest online anti-toxicity strategy

Do the mods dream of electric sheep?

"Toxicity" is one of a few words that has come to define today's internet culture, and for online game makers, it's arguably an even bigger issue than curbing cheating. Platoons of trust and safety officers have been raised, and over 200 gaming companies, including Blizzard, Riot, Epic Games, Discord, and Twitch, have joined the "Fair Play Alliance," where they share notes on their struggle to get players to be nice to each other.

Yet for all their efforts, a 2023 report commissioned by Unity concluded that "toxic behavior is on the rise" in online games. Now some companies are turning to the buzziest new tech around for a solution: machine learning and generative AI.

Back at the 2024 Game Developers Conference in March, I spoke to two software makers who are coming at the problem from different angles.

Ron Kerbs is head of Kidas, which makes ProtectMe, parental monitoring software that hooks into PC games and feeds voice chat, text chat, and even in-game events into machine learning algorithms designed to distinguish bullying and hate speech from playful banter, and to identify dangerous behavior like the sharing of personal information. If it detects a problem, it alerts parents that they should talk to their kid.

You don't have to be an eight-year-old Roblox player with concerned parents to find yourself being watched by robo-mods, though. Kidas also makes a ProtectMe Discord bot which hops into voice channels and alerts human mods if it detects foul play. And at GDC, I also spoke to Maria Laura Scuri, VP of Labs and Community Integrity at ESL Faceit Group, which for a few years now has employed an "AI moderator" called Minerva to enforce the rules on the 30-million-user Faceit esports platform.

"Our idea was, well, if we look at sports, you normally have a referee in a match," said Scuri. "And that's the guy that is kind of moderating and ensuring that rules are respected. Obviously, it was impossible to think about having a human moderating every match, because we had hundreds of thousands of concurrent matches happening at the same time. So that's when we created Minerva, and we started looking at, 'OK, how can we use AI to moderate and address toxicity on the platform?'"

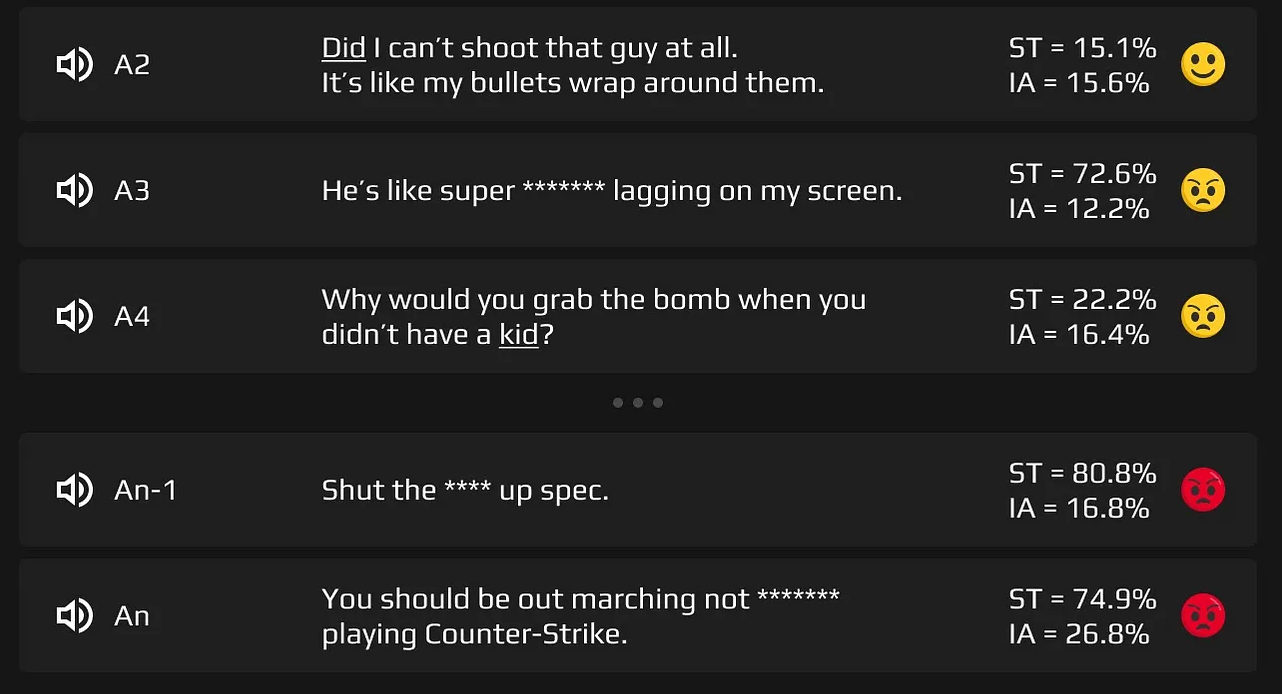

Faceit still employs "a lot" of human moderators, Scuri says, and Minerva is meant to compliment, not replace, human judgment. It is authorized to take action on its own, however: Anything Minerva gets right 99% of the time is something they're willing to let it enforce on its own, and for the 1% chance of a false positive, there's a human-reviewed appeal process. For things Minerva is more likely to get wrong, its observations are sent to a human for review first, and then the decision is fed back into the AI model to improve it.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Detecting bad intentions

One thing that distinguishes ProtectMe and Minerva from the simple banned words lists and rudimentary bots of yesteryear is their ability to account for context.

"How are people reacting to these messages and communications? Because maybe it's just banter," said Scuri. "Maybe it's just like, cursing, as well. Would you really want to flag somebody just because they curse once? Probably not. I mean, we are all adults. So we just really try to understand the context and then understand how the other people reacted to it. Like, does everybody fall silent? Or did somebody else have a bad reaction? And then if that happens, that's when [Minerva] would moderate it."

ProtectMe is also concerned with more than just what's being said in chat: It aims to identify variables like a speaker's age, emotional state, and whether they're a new acquaintance or someone the kid has previously talked to. "From the context of the conversation we can very accurately understand if it's bullying, harassment, or just something that is part of the game," says Kerbs.

Gamers are known for their aptitude for breaking or bypassing any system you put in front of them, and "they are very creative" about getting around Minerva, says Scuri, but robo-mods also aren't limited to monitoring chat, either. Faceit trained Minerva to detect behaviors like intentionally blocking another player's movement, for instance, to catch players who express their discontent with non-verbal griefing.

The latest frontier for Minerva is detecting ban evasion and smurfing. Scuri says that "actually really toxic" players—the one who are are incorrigibly disruptive and can't be reformed—are only about 3-5% of Faceit's population, but that small percentage of jackasses has an outsized effect on the whole playerbase, especially since banning them doesn't always prevent them from coming back under a new name.

Minerva is on the case: "We have several data points that we can use to understand how likely it is that two accounts belong to the same person," said Scuri. If a user appears to have two accounts, they'll be compelled to verify one of them and discontinue use of the other.

Eye in the sky

So, is all this AI moderation working? Yes, according to Scuri. "Back in 2018, 30% of our churn was driven by toxicity," she said, meaning players reported it as the reason they left the platform. "Now that we are in 2024, we reduced that to 20%. So we had 10 percentage points decrease, which was huge on our platform."

Meanwhile, Kidas currently monitors 2 million conversations per month, according to Kerbs, and "about 10 to 15%" of customers get an alert within the first month. It isn't always a super alarming incident that sets the system off, but Kerbs says that 45% of alerts relate to private information, such as a parent's social security or credit card number, being shared.

"I don't want to create a spying machine or something like that. I want to make parents and kids feel like they can talk about things."

Kidas CEO Ron Kerbs

"Kids who are young cannot perceive what is private information," said Kerbs, citing learnings from the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, a source of research for Kidas. "Their brain is not developed enough, at least in the young ages—six, seven, eight—to separate between private information and public information."

I can't imagine any parent wouldn't want to know if their kid just shared their credit card number with a stranger, but I also worry about the effects of growing up in a parental panopticon, where the bulk of your social activity—in a 2022 Pew Research report, 46% of teenagers said they "almost constantly" use the internet—is being surveilled by AI sentinels.

Kerbs says he agrees that kids deserve privacy, which is why ProtectMe analyzes the content of messages to alert parents without sharing specific chat logs. His intent, he says, is to protect young kids and train them to know how to respond to bad actors—and that offers for free V-bucks are not, in fact, real—so that when they're teenagers, their parents are comfortable uninstalling the software.

"I don't want to create a spying machine or something like that," he said. "I want to make parents and kids feel like they can talk about things."

If they're as effective as Kerbs and Scuri say, it may not be long before you encounter a robo-mod yourself (if you haven't already), although approaches to the toxicity problem other than surveillance are also being explored. Back at GDC, Journey designer Jenova Chen argued that toxicity is manifested by the design of online spaces, and that there are better ways to build them. "As a designer, I'm just really pissed that people are so careless when it comes to maintaining the culture of a space," he said.

For games like Counter-Strike 2 and League of Legends, though, I don't foresee the demand for a moderating presence decreasing anytime soon. Scuri compared Minerva to a referee, and I think it's safe to say that, thousands of years after their invention, physical sports do still require referees to moderate what you might call "toxicity." One of the jobs of an NHL ref is literally to break up fistfights, and the idea of an AI ref isn't even limited to esports: Major League Baseball has been controversially experimenting with robo-umps.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.