A game developer believes Steam Spy puts its employees in danger

After initially respecting some requests for data removal from developers, Steam Spy says it won't hide its data.

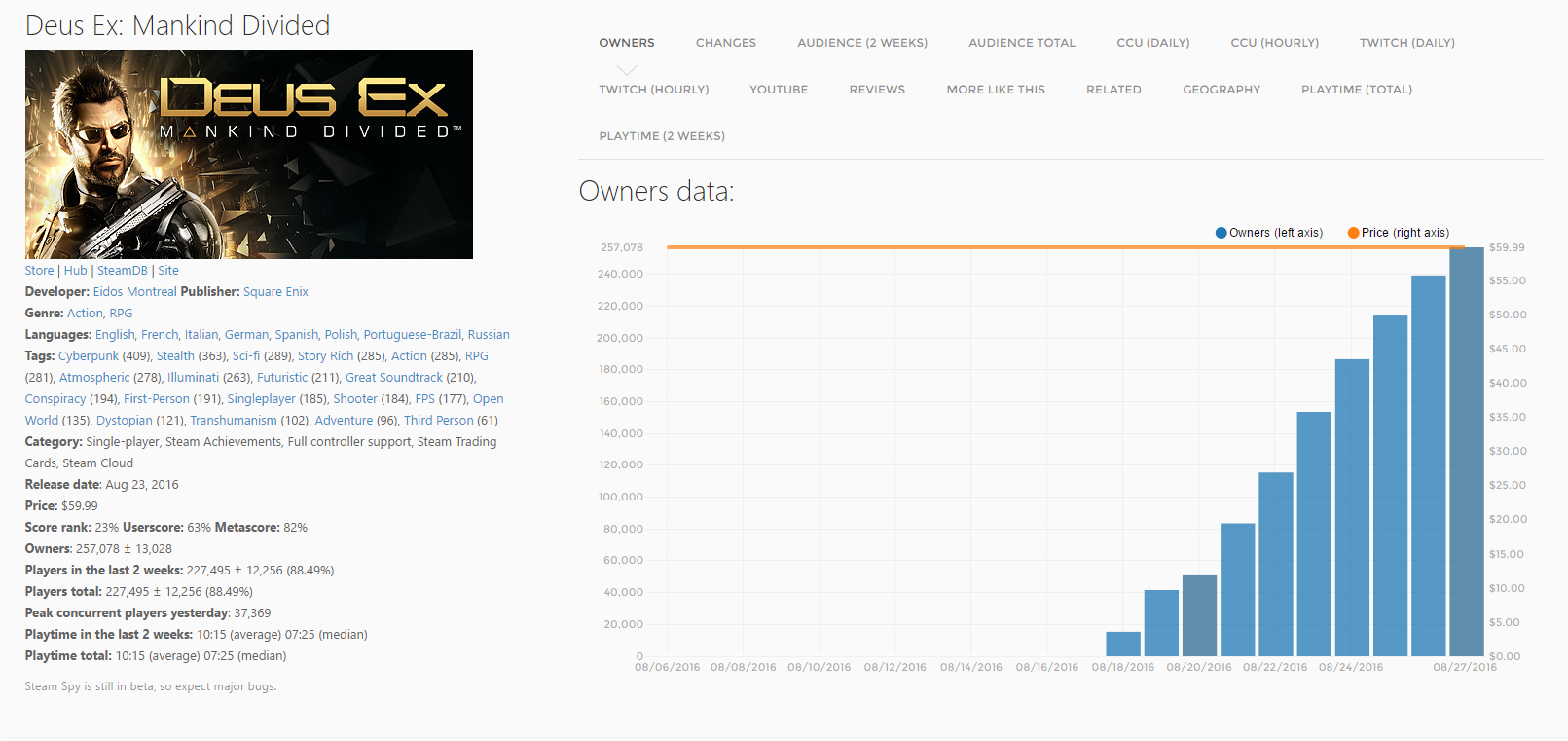

Steam Spy, a website which reports game sales estimates by scraping the libraries of public Steam accounts, will no longer make exceptions for publishers that have requested their games not appear on the site. Any exceptions previously made have been rescinded. The decision has surfaced a surprising concern: one game developer believes Steam Spy’s information could endanger its employees.

That developer, which says it has employees in non-developed countries, fears estimates of its private sales numbers could make those employees a target for crime, whether or not the estimates are correct. After offering this information on its stance, the developer later asked to be excluded from this article, and out of respect for that concern, we are not naming them.

Though the developer didn’t elaborate on what sort of danger its employees face, we can assume one: corporate kidnapping is a valid concern in developing nations, where kidnapping rates can be in the thousands per year—and that’s just what’s reported and recorded. Though The Economist reports that ‘express kidnappings,’ with less discriminating targets than those of more organized crime, are on the rise, there is no doubt that the threat of planned kidnapping for ransom exists in many parts of the world.

Steam Spy owner Sergey Galyonkin feels the hypothetical scenario where criminals would monitor Steam Spy to choose targets for extortion is too implausible to be a concern. “I grew up in Ukraine and, unfortunately, I’m aware of practice of businessmen kidnappings,” wrote Galyonkin in an email to PC Gamer last Friday. “But I highly doubt that [gangsters in the developer’s country] would be sophisticated enough to find [the game developer] on Steam Spy and estimate its revenue based on that data. Because I, as the creator of the site, can’t do that myself.”

Galyonkin notes that Steam Spy does not present any confidential data such as company revenue, but merely acts as “a polling service” which estimates how many people own a Steam game. He now feels developers are abusing requests for removal, which he says “would be similar to game developers requesting PC Gamer to remove reviews of their games because it hurts their business.”

It’s not entirely similar, because Steam Spy’s data is not an opinion, but an attempt to estimate sales data as accurately as possible. Steam Spy’s estimates provide the closest thing to a hard description of sales available on the web, updated dynamically over time as more people buy the game. Any major sales milestones are likely to be reported or discussed on forums like Reddit, but probably wouldn’t be if neither the developer nor Steam Spy reported any data.

The assertion that one can’t estimate revenue is also suspect. For instance, imagine a one-person game developer who has had moderate success on Steam. Take their game’s lowest recorded price, multiply it by the estimated sales, subtract Steam’s 30 percent take and estimated taxes, and you have a conservative estimate of an individual's real income.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Are not-perfectly-accurate sales numbers valuable information to the gaming public?

Galyonkin argues that if the data is truly dangerous, PC Gamer and other outlets should not report on Steam Spy at all, which he says only further publicizes the offending data. The game developer in question seems to share his opinion even though it is disputing Galyonkin’s decision. Despite both parties commenting while also objecting to this report—Galyonkin as a rhetorical device, and the game developer to avoid raising its profile—we feel the story raises an important issue that affects all game developers in developing nations and the publications that cover them.

That segues into one possible defense of Steam Spy: that its estimates have journalistic value. Are not-perfectly-accurate sales numbers valuable information to the gaming public? Yes, to varying degrees. We use them carefully in our own reporting to help measure the popularity of a game. Most recently, websites that record concurrent user data like Steam Spy and SteamDB helped us report on No Man’s Sky’s unprecedentedly big launch.

In other cases, estimated sales figures could be used to support investigative reporting—it helps to know how successful a company may be when looking into questions of how it treats employees, when layoffs occur, and so on. However, while I did find accusations of employee mistreatment—eg, poor pay—regarding the developer in question, none of it uses or requires Steam Spy’s numbers. Knowing specifically how successful the company is could be valuable in a report on, say, corruption or illegal behavior, but I haven’t found any evidence of that.

This isn’t Galyonkin’s argument, though, as Steam Spy does not purport to be an independent resource in the first place, but a tool for developers. Paradox, one of the companies formerly excluded in Steam Spy by request, said about its removal that Steam Spy’s estimates are “wildly off at times” and complained that misleading data was being used in real negotiations. Galyonkin rebutted those remarks, but originally honored Paradox’s request and said, “I firmly believe Steam Spy should be seen as a useful tool by developers, not as a threat.”

While many developers openly celebrate sales milestones, or are seemingly indifferent to Steam Spy, the developer in question clearly does consider Steam Spy a threat—and not to its business negotiations, but to its safety. It isn’t, however, a threat I can precisely assess, and my source didn’t elaborate other than to say that they consider the data dangerous.

“I don’t want to deal with distinguishing between ‘valid’ causes for the game removal and ‘invalid.’"

Sergey Galyonkin

As Galyonkin asserts, it is difficult to imagine Steam Spy raising a company’s profile any more than regular press and critical praise, a Metacritic page, Steam reviews and concurrent player counts, Reddit discussions, and the like. But if a developer who intimately knows its own region’s political and criminal situation feels uncomfortable with the data, and Steam Spy is made for developers, why report it? According to Galyonkin, he originally removed games as a goodwill gesture, but now has to take a no exceptions policy to avoid “other companies misunderstanding the nature of Steam Spy and issuing demands for removal of the data.”

“I feel that in order for Steam Spy to remain a useful tool for game developers, I have to stop the abuse of the system by game publishers,” wrote Galyonkin. A request for removal from Dying Light developer Techland spurred the decision.

I asked Galyonkin if, despite that position, there is any potential case compelling enough that he would again honor a developer’s request to be removed. He says no. “I’m not a court,” wrote Galyonkin. “I don’t want to deal with distinguishing between ‘valid’ causes for the game removal and ‘invalid.’ Can a single person do this, honestly? I am certainly not qualified.”

I suspect that Galyonkin is qualified to judge the difference between a request from a studio in a developing nation and a request from a publisher who simply dislikes Steam Spy’s data, but doesn't want to make that judgment or be slowed down by hearing requests, which he says he's getting "way more" of after Paradox made a point of it. Now that the new policy is in place, any company that wishes to be excluded can only push Galyonkin to reverse his decision—Steam Spy’s information is gathered from public sources and its accuracy is caveated, so it’s unlikely there’s any legal grounds for obtaining removal. The developer I spoke to says it will continue to pressure Galyonkin to remove its data.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.