Why I Love: Stealth on ships

In Why I Love, PC Gamer writers pick an aspect of PC gaming that they love and write about why it's brilliant. Today, stealthing around ships. We don't know why all the best stealth levels are set on boats, but they are.

Due to the popularity of military shooters, the ship level has become cliché. It's the genre's lava level. Inevitably, it has a TV Tropes page.

I don't care. I love them. Specifically, I love them in stealth games, where they act as a setting, rather than a set piece. That bit where you're running through a semi-cinematic disaster movie, an invisible trigger sending the next wave of flooding water crashing through a door? I'm not a fan, thanks Tomb Raider. Scripting robs the setting of that sense of separation from the outside world; the idea of a small, confined, claustrophobic space with no escape and no backup. Not just for me, but for them—the guards.

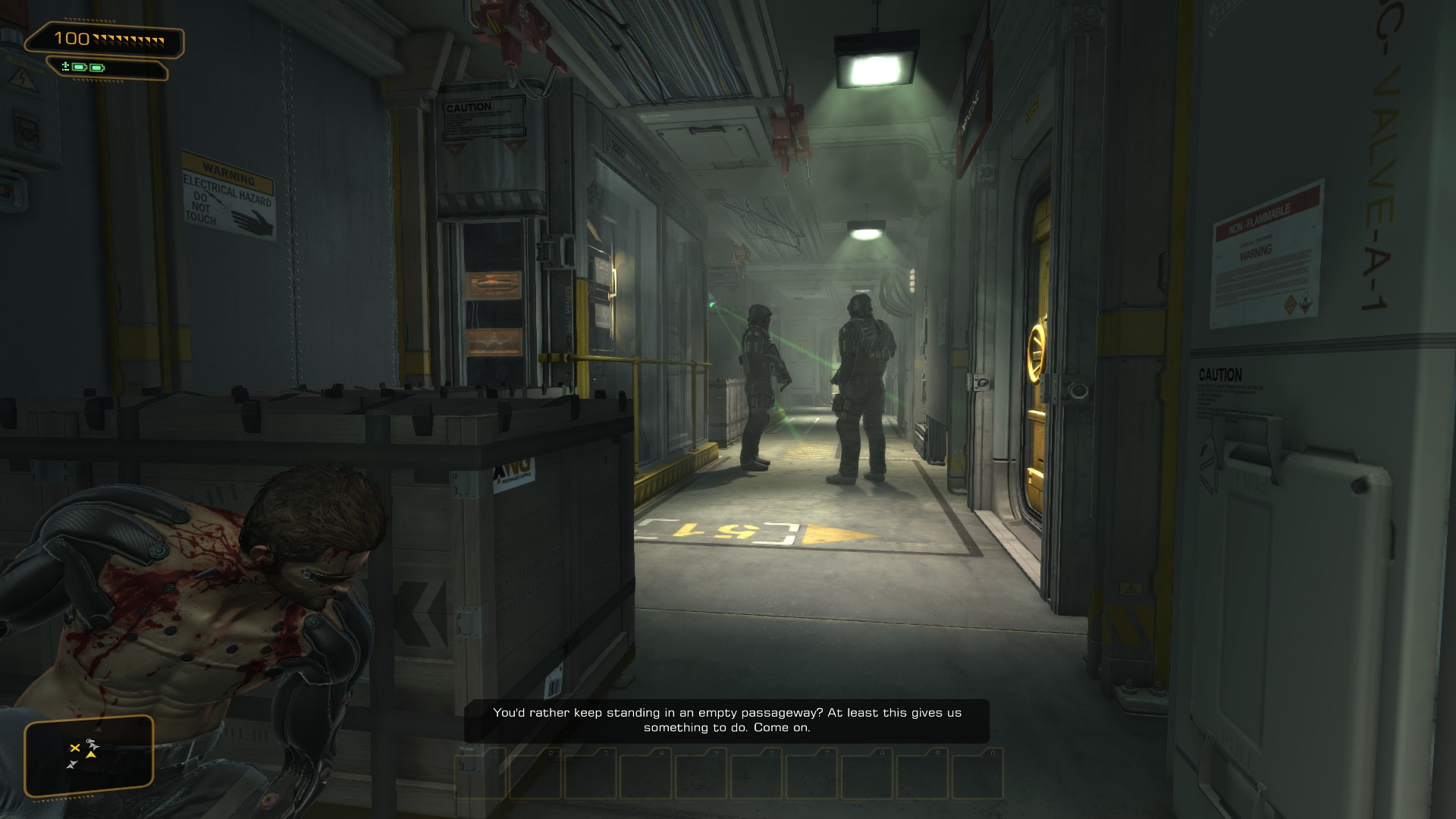

Deus Ex: Human Revolution's Missing Link DLC opens on a ship, and it's one my favourite sections of the game. There is a very functional design philosophy to a big floating boat that sits at odds with the game's stylised futurism. In the open cities and sprawling office complexes, Deus Ex could lace its environments with high-tech design. The ship is just a ship. The scale is different—narrower, more linear. It's filled with plain, metallic walls. The doors are bulky slabs of mass. It feels solid. Real.

See also: the original Deus Ex, or Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory. These levels stand apart as standalone vignettes contained with the overall flow of their respective campaigns.

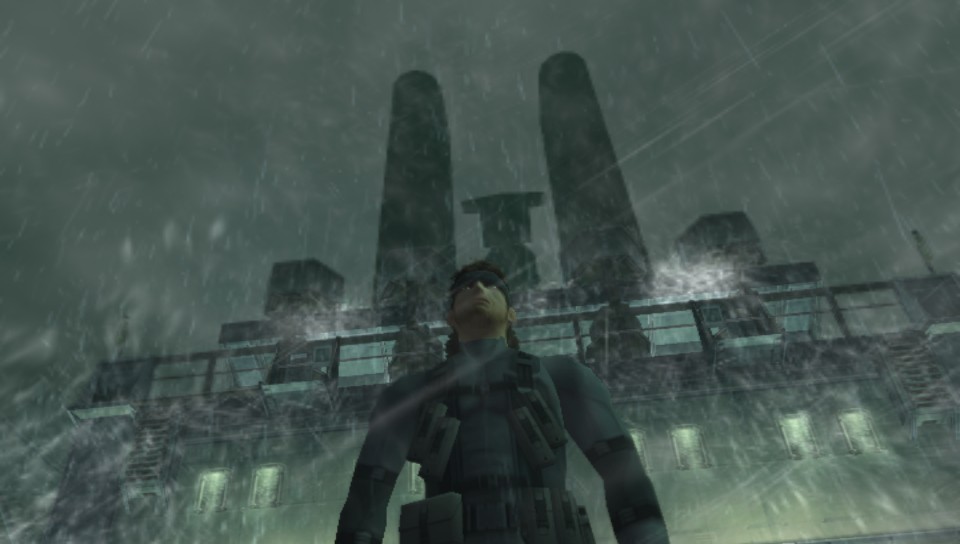

It's pure coincidence that I'm writing this on the week of Alien: Isolation's release, but it's fitting. That is, to all intents and purposes, a stealth game set on a ship. But it occupies a different mental space than what I'm talking about here. In many ways it's the opposite. The film Alien is about a crew trapped in an inescapable place with a unstoppable killer. It is a film about being hunted. But take the opening Tanker chapter of Metal Gear Solid 2—it flips the concept. Your enemies are the ones trapped in an inescapable space, and you are the unstoppable killer.

I was about 17 when the Metal Gear Solid 2 demo came out. It was around the same time I was discovering horror films. The demo—containing the first section of the Tanker prologue—felt like a powerful, cathartic inversion to the stories I was watching. It manifested as a fascination with toying with the guards. First, I'd shoot out their radio, disabling communication with the ship at large. Then, I'd move. Give them a glimpse that something is out there. Finally I'd strike.

I should probably point out that I'm not a psychopathic monster. Games can, to the outsider, be horrifying. My repeated MGS2 playthroughs probably looked like sadistic torture sessions—another young mind corrupted by violence and giant seafaring transport vehicles. That's not the case—if anything, the experience felt more like I was directing a movie. None of it was real, so what story can I tell? How about a story where the monster wins.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

In Hitman: Blood Money, the monster is even more insidious. He hides in plain sight.

In Hitman: Blood Money, the monster is even more insidious. He hides in plain sight. Here, 47 is essentially the Thing—another film based on horror in a remote environment. In the Death on the Mississippi level you discover members of different social strata scattered throughout compartments of the ship including workers, revelers, and, of course, your intended victims. With care, you can move through them all, a powerful subversive presence that, if you're playing as intended, passes unseen. I always play stealth games as perfectly as possible, often reloading if the fantasy of hunting through these spaces is broken.

The ultimate example is Coloratura, the winner of last year's Interactive Fiction competition. In it, you're a literal monster—pulled from the deep and tasked with finding your way home. The monster's actions are initially obfuscated by its alien thought patterns, but eventually, as you work out what you're doing, you'll realise the effect that you're having on the ship's human inhabitants. And then you'll keep doing it anyway.

To an extent you can pull this off in any remote setting. But there's something about the sea that makes the concept so irresistible. In every direction is a vast and inhospitable ocean, and I'm the most deadly thing on it.

Phil has been writing for PC Gamer for nearly a decade, starting out as a freelance writer covering everything from free games to MMOs. He eventually joined full-time as a news writer, before moving to the magazine to review immersive sims, RPGs and Hitman games. Now he leads PC Gamer's UK team, but still sometimes finds the time to write about his ongoing obsessions with Destiny 2, GTA Online and Apex Legends. When he's not levelling up battle passes, he's checking out the latest tactics game or dipping back into Guild Wars 2. He's largely responsible for the whole Tub Geralt thing, but still isn't sorry.