What’s the next big leap for 3D graphics?

We talk to Epic Games and Nvidia about the future of photorealistic real-time graphics and simulated worlds.

You may remember a YouTube video from a few years back that makes incredible claims: that right now, on current hardware, we can build game worlds with unlimited detail. There’s no polygon count because there are no polygons—we’ve moved beyond stitching together thousands of flat shapes to make 3D models and now everything can be built from individual ‘atoms.’ And because only the visible atoms are rendered, it’s extremely fast, and there’s no limit to the size of the point cloud data. It can even render every grain of dirt on the ground.

That video was created by Euclideon, an Australian software company that promises its point cloud search algorithm is revolutionary, and it does look awfully impressive. But Euclideon has since become a bit notorious for making bold claims and then brushing off industry skeptics, and in the five years since that video we still haven’t played a game using its supposedly transformational technology. That doesn’t necessarily mean it doesn’t work, but if it’s really the future of real-time rendering, it certainly hasn’t been proven—so far Euclideon has only demonstrated rudimentary lighting and animation.

But the future of real-time 3D graphics may be more incredible than even Euclideon’s hype videos suggest. To find some clarity on these claims and other futuristic ideas, I spoke to graphics leaders in both software and hardware: Epic Games co-founder Tim Sweeney and Nvidia director of technical marketing Tom Petersen. I wanted to find out where videogame graphics really stand now, how close we are to truly simulating the real world, and what the future might look like even beyond photorealism—or “the next stage of humanity,” as Sweeney puts it. It’s bit scary, really.

Simulating light

The humble polygon probably isn’t going to be usurped anytime soon, but the idea of non-traditional rendering isn’t without merit. Had monitor resolutions not increased at the rate they did, says Sweeney, the world of real-time graphics processing might have gone in another direction. But it turned out that the efficiency of polygon rendering was the best way to keep up with increasing resolutions, and because we’ve gotten really good at rendering polygons over the past 10 years, other methods are going to have a hard time breaking in. Were something else to win, it would not only need to be better than the tools available to game developers now—tools for animation, world building, fluid and cloth simulation, and so on—but also do it at a disadvantage because the industry and hardware is all optimized for rasterizing polygons.

"Analytically antialiased micropolygon rendering (from the original Pixar REYES paradigm) is a promising [technique], and the only option I see as a plausible pipeline-wide replacement for traditional rasterization,” wrote Sweeney when I later asked him to elaborate. “It would win in a scenario where fine details like hair or vegetation are essential, and GPU performance has outgrown pixel density. The former condition holds nowadays, but the latter is just the opposite as 4K and VR are demanding ever-higher resolutions.”

In other words, we still don’t have the processing power to render film quality graphics in real-time at the resolutions we’re trying to achieve, but it's not impossible. “Other interesting approaches are raytracing, voxel rendering, signal space volume rendering as is done for medical MRIs, and point clouds,” said Sweeney. “I think each of these could excel for particular usage cases and effects, but I'm skeptical of them being a replacement for the entire traditional rendering pipeline."

To deliver photorealism that is indisputably accurate of real life, I think you’re going to want to have a light simulation.

Tom Petersen

Above: Imagine Pixar quality rendering in real-time.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Petersen, of Nvidia, describes our present real-time rendering capabilities as “sleight-of-hand approximations,” and does see new techniques as part of a future in which those approximations become true simulations. “To deliver photorealism that is indisputably accurate of real life, I think you’re going to want to have a light simulation,” said Petersen. “That will require, to some degree, different techniques.”

For games that strive for realism over style, Petersen envisions a less artistic, more technological approach to graphics. Rather than an artist painting a texture, they simply build a model and say, “Hey, here’s a piece of wood.” The properties of wood would have been captured from real samples, then sent to the GPU to be converted into images.

“I think doing a physically accurate simulation for materials for light is going to become more and more powerful,” said Petersen. “We’re not close to that today, but that could be a way things go. I love the idea of having a simulation of light that uses materials and material properties rather than these sort of artistically rendered textures and simple properties.”

While that’s a ways off, point clouds, scans, and photogrammetry do already have a place in videogames. The world of The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, for instance, was achieved by photographing real world objects, constructing point clouds, and then converting the clouds into polygons and textures. The final result runs just like other games, but looks far more convincing because the detail is real. Stones are worn the way stones wear rather than being wallpapered with a stone-like image, and even though we aren’t looking at micropolygons or point clouds or signal space volume rendering, the effect is remarkable.

Breaking Moore’s Law

As GPU processing power increases, the complexity of polygonal scenes will of course keep increasing, whether they’re built by hand or scanned, and some of those alternative rendering techniques may become possible. And for the foreseeable future, GPUs are going to keep getting better, and fast.

“GPUs are still progressing faster than Moore’s Law, because obviously we can go parallel and when you go parallel it really does improve performance quite dramatically,” said Petersen. “So I expect that GPUs will continue to get faster and faster and faster on roughly the same pace through a combination of process and architectural improvements.”

Will it ever tail off? “You never know,” he says, but typically “life finds a way.” Every time someone says it can’t be done, that there’s no more processing left, the technology gets better anyway.

The number of polygons we can render isn’t everything, though. More polygons might make buildings look great, and the trees better than ever, but I’m always disappointed when I look at the ground—it’s very apparently made of flat shapes and textures. It’s not thick dust or mud absorbing light, molded by every force that’s ever acted on it. And even if we could render every particle as in Euclideon’s demo, it would still be missing a vital part of its fidelity: that dirt is supposed to spread under our feet and spill into wind currents, not be superglued to the bedrock.

Behavior is just as important to fidelity as polycount or texture resolution, and ‘photorealism’ is really a poor way to describe what we’re moving toward, which is something more like high definition video, except even better: more real looking than what a camera lens produces, as well as dynamic and malleable.

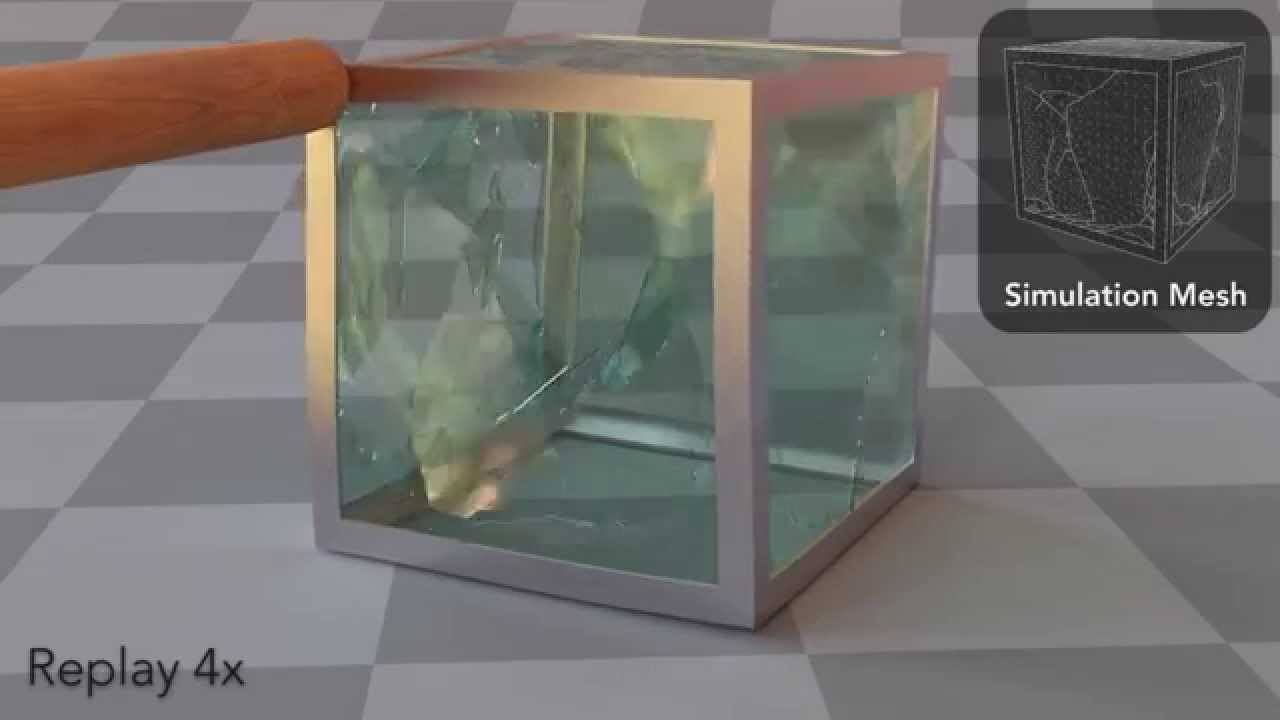

Water, mud, and other soft, squishy, and liquid things are tough to simulate, but GPUs are getting much better at it. They’re no longer just polygon rasterization machines, but powerful general computing devices that can crunch physics and AI simulations. The results in just the past several years have been stunning—check out this Nvidia FleX demo from 2014 (embedded above), for instance.

There are quite a few games that have put hardware accelerated physics simulation to good use. Dangerous Golf uses FleX fluids, for instance, as does Killing Floor 2 for its blood and gore. The tech demos always look a little more exciting to me than the games themselves, but all demos have to do is look good—game developers have many more concerns beyond crying over the fidelity of spilt milk. I asked Petersen about my dirt, specifically. When will dirt in a game be like dirt?

I think you’re going to see streaming technology improve dramatically over the next several years such that it blurs the line between what is local and what is in the cloud.

Tom Petersen

“We don’t know when it’s going to happen, and obviously breakthroughs happen all the time, in terms of, ‘Oh, we don’t have to simulate every particle [of dirt] to get a great effect, we can do particle copies and we just kind of have models of these particles scattered all over the place,’” said Petersen. “But I do think that the challenge for Nvidia and the challenge for graphics companies is going to be: how do you get more towards what you’re saying, simulating everything, while delivering real-time performance? And I think you’ll see approximations along the way. As GPUs get faster and faster and faster we’re still going to want to spend our GPU computing effort on things that matter to the view.”

Above: A SIGGRAPH 2015 presentation demonstrating some of the simulation problems being tackled in academia today.

According to Petersen, our desktops are going to “rapidly approach photorealistic quality” as GPUs improve—and simulation comes alongside that—but his more blue sky future predictions also include cloud computing. “I think you’re going to see streaming technology improve dramatically over the next several years such that it blurs the line between what is local and what is in the cloud,” he said. And though VR will need fast local processing to keep up with the head tracking, Petersen imagines a hybrid computing model that splits the work between a lightweight device and remote processors, untethering VR headsets.

Streaming between our own devices is one thing, but the prospect of remote computers simulating our game worlds is both exciting and somewhat off-putting. We used to own software (or at least that was the illusion), and now we license it, and at some point in the near future we may not even process it ourselves. But as Petersen points out, we’ve come to accept services like Netflix, so it’s not a big stretch to think the young generation will adopt streaming technology as it advances. The good news is that our local hardware is going to be amazingly powerful as well.

What's missing?

For Sweeney, the most interesting problems are the ones we can solve right now with software, and perhaps could have solved five years ago if we’d only thought of them. “We have this very powerful hardware technology here,” said Sweeney, “but I feel like we’re only barely utilizing it in terms of its full potential for human activity.” He points out that multiplayer hasn’t changed much in 20 years—we’re still all emotionless avatars “without any connection to other people.”

I feel like we’re only barely utilizing [current hardware] in terms of its full potential for human activity.

Tim Sweeney

“What happens when you can realistically capture people’s faces in real-time through inward-facing cameras while they’re in VR, and their body motion, and recreate them as digital humans within a VR environment?” he asks.

Sweeney also considers development tools to be a vital part of the future: getting better world building tools into Unreal Engine, including the ability to create in VR, and to users who aren’t professional game developers. His vision of the future includes a generation that grew up on Minecraft now building photorealistic environments in their spare time.

“If we think about what gaming might be in 10 years, we‘re not just going to be playing a bunch of prebuilt single-player games that companies had thousands of people construct on a billion dollar budget,” said Sweeney. “It’s going to be user driven. Users are going to build stuff, they’re going to build seamless environments for social interaction, for gameplay. It’s all going to be about empowering the users to make this stuff happen on their own. You’re going to see the indie community of millions of indies contributing to that as opposed to shipping 400,000 games in the App Store which mostly fail.”

That brings up an important topic: who is going to build these absurdly detailed worlds? The biggest studios already use hundreds or thousands of people to build games, so it seems likely that the industry will become even more collaborative. And as Sweeney says, aside from hardware creators, standards holders like Microsoft, and engine and middleware developers, users may also become a bigger part of the process. Though the idea was abandoned, when Daybreak Games was SOE it had planned to source user-made environments from EverQuest Next Landmark for EverQuest Next. Perhaps it was ahead of its time.

I also asked Sweeney to take a wild guess at a more distant future—20 years from now—and his ideas are believable if bold. “We’re getting closer to simulating reality,” he said, and in 2036 “we’ll have rendering of physical objects so perfected that you’ll have a very, very hard time distinguishing those objects from reality.” We’ll also have smartphones in our pockets that render hyperrealistic augmented reality worlds to devices no more cumbersome than sunglasses.

For perspective, the Nokia 9000 Communicator, a cellphone introduced 20 years ago in 1996, had a 33 MHz processor and 8MB of memory. The top-tier iPhone 6s has a 1.85 GHz processor, 2GB RAM, and 128GB storage. And in another 20 years, Sweeney thinks it’ll be “like having a better PC than you can possibly buy today with you everywhere you go at all times, and better and more immersive graphics, even in a mobile form factor, that you can buy for a million dollars today.”

“And yeah, I think in 15 years a billion people will have this,” he said. “And that’s really going to change things. You know, the next stage of humanity, basically. It’ll be a superpower.”

It’s difficult to reckon with such grand predictions. The present has a way of feeling mundane, something the past arrived at along a slow, obvious course. The invention of the microchip, the personal computer, the GPU—it’s all reasonable, well-understood, and very little like a superpower. But pluck the facts out of the timeline and recent history becomes a series of impossibilities: 10 years ago VR was science fiction; 20 years ago Quake had the best graphics I’d seen; 30 years ago a personal computer cost as much as a car. In the grand scheme, it doesn’t really matter whether or not Euclideon or any other technology company can actually do what it claims—someone is going to simulate the world one way or another.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.