How Treyarch escaped Infinity Ward's shadow

The rise of Call of Duty's second studio.

The Gray Matter bundle is a cosmetic purchase available for 1,600 COD Points in Black Ops 4. It’s as mundane as it sounds—you get to unlock a fancy reactive camo effect for your weapons, but ultimately it’s just another pack in a multiplayer service game. Yet it’s also a tiny tribute, to a tiny studio that exerted an invisible influence on Treyarch during the most critical period in its history.

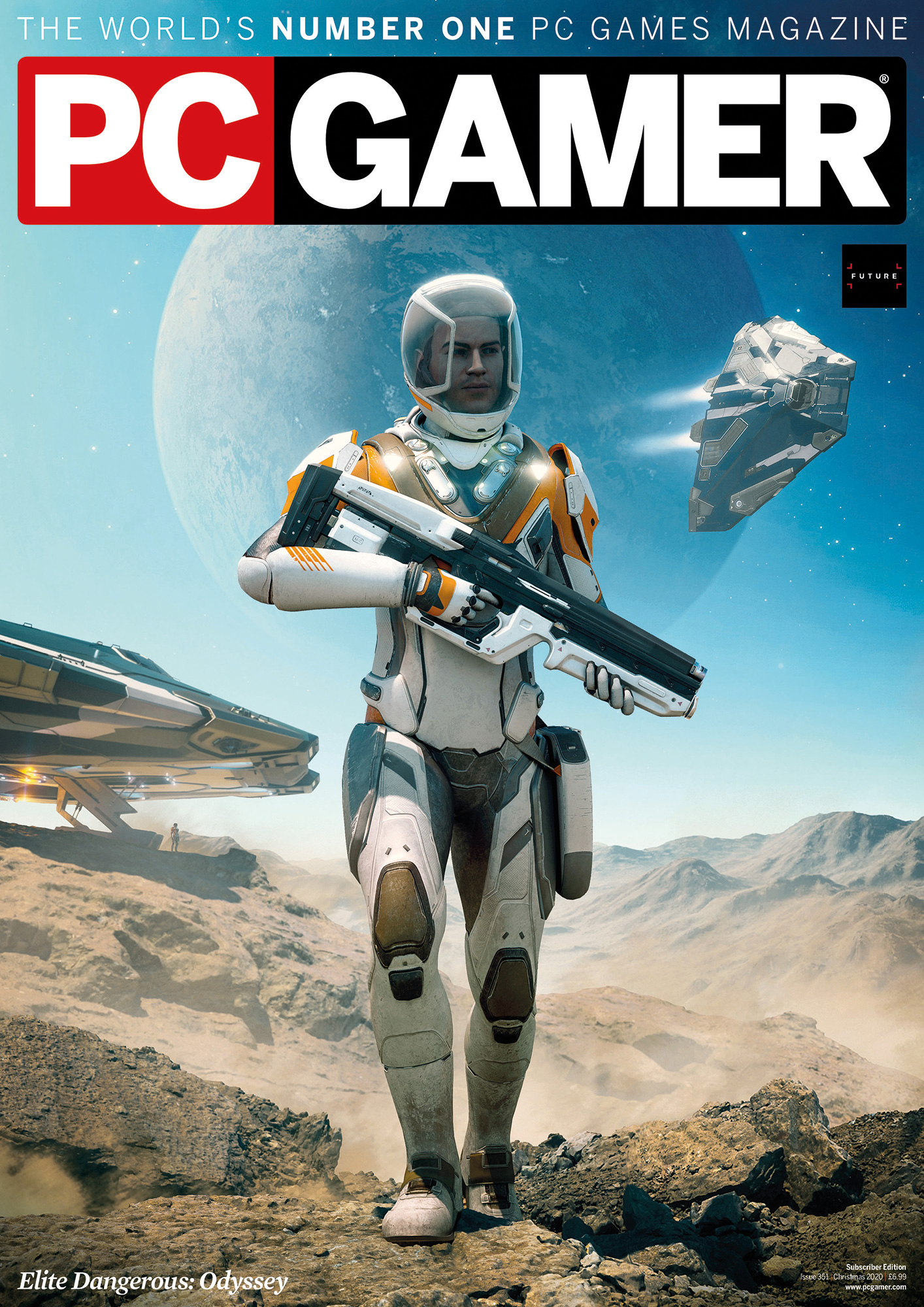

This article was originally published in PC Gamer UK 351. You can get our glossy mag fired through your letterbox each month by subscribing.

Gray Matter Interactive was the developer behind Return to Castle Wolfenstein. In the '90s, it had made the Redneck Rampage games: sweary, gory, and self-consciously controversial first-person shooters that achieved the highest honour of the time—impressing id Software.

To Gray Matter, id entrusted BJ Blazkowicz and the daunting task of updating Wolfenstein 3D—an FPS so rudimentary it had no ceilings or floors—for a new millennium. The studio leaned hard into the occult elements id had only alluded to, reimagining the series as a pulp adventure. The initial demo even included an alarm sound from Raiders Of The Lost Ark.

Played today, Return to Castle Wolfenstein marks a clear transition point for the FPS genre. In its early levels, castle corridors and secret rooms evoke Doom and Quake. Then, as it breaks out into the German countryside, it predicts the stealth and freedom of movement to come in Far Cry. Finally, it enters the bombed-out ruins of Kugelstadt, realising the cautious house-to-house combat Medal of Honor had reached for on the PlayStation.

While the zombies took liberties with history, Gray Matter’s research was meticulous, and Activision recognised an opportunity. When Infinity Ward built Call of Duty, it did so on the Return to Castle Wolfenstein engine—and when the game needed an expansion, Gray Matter was there, wielding a perfectly modelled MP40.

Call of Duty: United Offensive was a huge hit, but like the events it depicted, it represented the heroic efforts of just a few brave men and women. There were no more than 18 names in Return to Castle Wolfenstein’s credits, and as AAA development teams grew larger, Activision decided to bolster its ranks.

Brain bank

Gray Matter was then folded into Treyarch—a studio which had its own PC gaming past in notorious sword- wobbler Die by the Sword. By the mid 2000s, though, it was churning out console games for Activision, at a rate of sometimes up to three a year.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Though Gray Matter’s name had been subsumed by Treyarch’s, its spirit was evident in the games that followed. Call of Duty: World at War was a straight historical shooter on the surface, but pushed the series into horror for the first time. In retrospect, the Pacific missions were problematic—its Japanese soldiers were characterised as zombies, frenzied and mindless. But the Russian segment of the game was a narrative highpoint for Call of Duty, and arguably Treyarch’s artistic peak.

The monologues of Red Army sergeant Viktor Reznov, played with a huge amount of vigour by Gary Oldman, lent the campaign real poeticism—and as the Russians marched on Berlin, that inspiring voice slid sideways into bloodlust and revenge. It was the first time Call of Duty had stepped outside the respectful tone established by Medal of Honor, finding a new and more complex sense of unease.

Something cold, something new

Revenge and unease became favourite themes of Treyarch’s as the developer embarked on its defining project: Black Ops. Studio chairman Mark Lamia persuaded Activision to consolidate the developer’s teams for an ambitious two-year gamble. No longer would Treyarch play second studio to Infinity Ward, but instead leapfrog Modern Warfare, building on its moral ambiguity and contemporary setting with a story that ran from the Arctic in 1945 to Vietnam in 1968.

By Black Ops 2, Treyarch was one of the most famous game studios in the world.

Obsessed with CIA cover-ups and brain programming, Treyarch’s storytelling became increasingly dark and traumatic, while Gray Matter’s horror background shone through in ghoulish direction and even a few jump scares. With the returning Viktor Reznor whispering in their ear, players were left unsure of what was real or who they were fighting for. At times, Black Ops endorsed an anti-nationalism bent at odds with the Call of Duty games before it; at others, it simply seemed nihilistic. Whatever their politics, these grim flashbacks resonated, and Lamia’s gamble paid off.

By Black Ops 2, Treyarch was one of the most famous game studios in the world, with the confidence to match. Its new stature revealed an experimental streak; the company introduced quasi-RTS levels to its campaign, and built a surprisingly malleable story that was altered by the player’s behaviour in key moments.

The branching plot, however, chafed against the often restrictive play. In a bid to provide ever more cinematic set pieces, Treyarch tightened its grip over player movements, leading to QTE-like action scenes that asked for very little action. The dissociation could be profound, as if the player was merely the actor, and a body double was performing all of the stunts.

Worse, as Black Ops moved into the near and then distant future, it revealed a fixation with teenage toys. If a teenage sensibility had taken root at Treyarch, however, that’s because it had long been rewarded with the pocket money and admiration of teenagers.

Dead ahead

In truth, Treyarch’s experiments have tended to connect best when drawing on Gray Matter, rather than its actual grey matter. Late in development, the World at War team added a co-op zombie horde mode to its serious shooter, in order to blow off steam. That’s what has lasted over a decade: a horror spin-off, just as Return to Castle Wolfenstein was to Wolfenstein 3D.

The other COD studios only rarely dabble in Zombies—it’s one of the few things that still differentiates entries in the annualised series. Over the years, the mode has become Treyarch’s signature, developing a mythology that spans dimensions. But when a player sits down with Zombies, everything they need to know is immediately understood. Overcomplicated, yet fundamentally dumb fun; it’s hard to imagine an idea more Treyarch than that.

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.