Remembering the Morris Worm, the first internet felony

In 1988, the US military was invaded by a BSD UNIX worm. It was an accident (mostly).

On a Wednesday in November of 1988, just a few days before his 24th birthday, Cornell graduate student Robert Morris released his creation onto the internet. And then he realized what he'd done.

With help from a friend at Harvard, Morris tried to warn other researchers with an anonymous Usenet post, but it was too late.

Morris' program spread through ARAPNET and the NASA Science Internet, infecting anywhere from hundreds to thousands of systems, depending on who's doing the estimating. Overnight, computer systems at six universities, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories, and other military and research sites ground to a halt.

The problem wasn't that the worm infected the computers. That alone would have done nothing except expose security flaws. The problem was that it reinfected them, and then re-reinfected them, again and again until they were so clogged with worm processes they couldn't function.

The Morris Worm, as it's called now, wasn't meant to cause any harm. Unlike a virus, a worm is a self-replicating program with no harmful 'payload.' But Morris didn't want his worm to be easily contained. If he told it not to infect machines that were already infected, his clever colleagues could simply feign infections to immunize their systems. Instead, he gave it a 1-in-7 chance of reinfecting a system that said it was already infected, so that it couldn't be tricked.

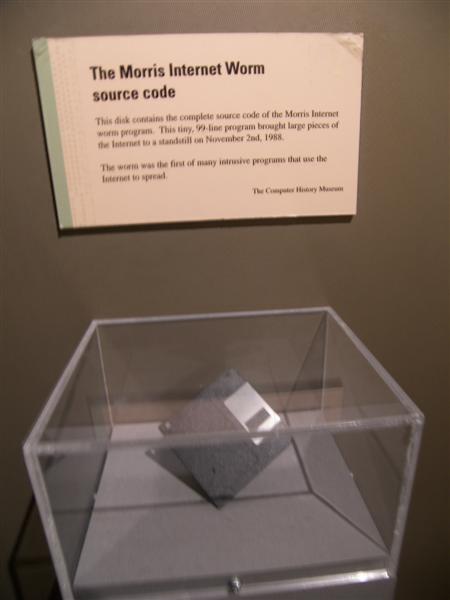

A floppy containing the Morris Worm source code at the Computer History Museum. Photo by Smart Destinations.

He had made a terrible mistake.

In 1990, Morris' lawyer argued that he didn't mean for the worm to reinfect machines at such a rate that they became inoperable. It was an accident, and Morris apologized for it on the stand.¹ He had only intended to demonstrate UNIX security flaws in Send Mail and the finger demon, the danger of weak passwords, and other vulnerabilities. The prosecutor, on the other hand, called it a "full-scale assault."²

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

There was no damage to the systems, just a bit of lost time while they were made operational again, and the security holes were fixed quickly—a bunch of computer science students faced an all-nighter that Thursday—so Morris' stunt is not seen today as a malicious attack by any means. It was the first major internet worm, and it was (mostly) an accident.

Despite the claim that the chaos he caused was accidental, however, Morris became known for another first when he was convicted of a felony under the 1986 Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

Morris appealed, but the conviction stuck: Three years probation, a $10,050 fine, 400 hours of community service, and the costs of his supervision.

Legal precedent and the genesis of security

The court case and failed appeal established an important legal precedent: 'White hat' hackers don't have to intend to cause harm to be convicted of a felony. Just the intent to gain unauthorized access to a system is enough—even if they do nothing with that access.

It was the 'oh shit' moment that spurred researchers into taking security seriously.

In retrospect, prosecutor Mark Rasch told the Washington Post in 2013 that he thinks Morris should be pardoned. "I would represent him if he wanted," Rasch told the paper. "He was not a bad person. I don't see any reason he should have to wear this as a mark of shame for the rest of his life."

It was the 'oh shit' moment that spurred researchers into taking security seriously. Prior to the worm, the internet was a relatively small science community and security didn't get much consideration. After the worm was contained, DARPA established the Computer Emergency Response Team.

Though someone else surely would have exposed the risks posed by open or poorly-protected servers had Morris not, he's the one who lit the match that spawned the modern computer security industry.

Can people catch computer viruses?

If they want to get a fungus when someone spills coffee on their keys, OK, but a virus belongs to people who can feel and throw up.

Erma Bombeck

More broadly, the Morris Worm spread awareness of the internet in general, which was on the verge of becoming a commercial space, and helped popularize the words 'virus' and 'worm' in relation to computers. At the time, many people had no clue what the internet was at all—it was the domain of universities, not everyday Twitter meltdowns.

MIT researchers Mark Eichin and Jon Rochlis told WaPo that the media was disappointed that the worm "did nothing even remotely visual" and that it didn't signal the start of World War III. Computer scientist Eugene Spafford told the paper that one reporter asked earnestly if people could catch a computer virus.

For syndicated humorist Erma Bombeck, it was all just absurd.

"Frankly, I don't like computers taking on human airs," Bombeck wrote in her column after the worm became national news.⁴ "If they want to get a fungus when someone spills coffee on their keys, OK, but a virus belongs to people who can feel and throw up."

Morris is now a partner at Y Combinator and tenured professor at MIT, which funnily, is where his worm originated (he'd have been foolish to distribute it from a Cornell computer, where he went to school). As far as I can tell, he hasn't spoken publicly about the incident that made him famous since the trial.

---

1. Lee, T. B. (2013, November 1). How a grad student trying to build the first botnet brought the Internet to its knees. The Washington Post.

2. Hacker gets probation for paralyzing system. (1990, May 5). The Deseret News.

3. United States v. Robert Tappan Morris, 928 F.2d 504 (2d Cir. 1991)

4. Bombeck, E. (1988, November 29). Nation Catches Computer Virus. The Victoria Advocate.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.