I kinda miss how much of a pain in the ass it used to be to play games online

There were little joys in finding tools like Hamachi to make those early 2000s online gaming problems evaporate.

There are only a few applications I have running at all times on my PC these days. I don't need Microsoft Word when I can do all my writing in Chrome. Discord replaced three separate chat applications, taking over for my instant messaging client and Ventrilo voice server and mIRC chatrooms. It's now so ubiquitous to be able to right-click a friend's name in Steam and invite them to a game lobby that I'm stunned when a game occasionally asks me to type in a lobby code instead. It seems almost unthinkable that not so many years ago I ran a tiny program on my computer at all times with a singular purpose: making online gaming less of a pain in the ass.

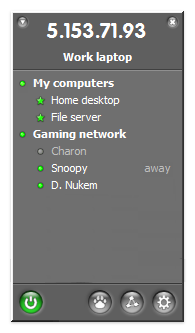

I don't remember when I finally uninstalled Hamachi—probably in 2016 or so, when it was clear its services were no longer needed. But for a few years it was the skeleton key of PC gaming: a near-magic solution to practically any online gaming headache imaginable. Before Hamachi, there were hours spent mucking with port forwarding and trying to understand what the hell a router's NAT type was. After Hamachi, there was just a little green light that said "you're good to go."

Hamachi debuted in 2004 as a simple way to "make software designed for local networks work over the internet," as explained on a website still maintained by its original creator. Hamachi is essentially just a VPN client, but one built at a time nobody was talking about VPNs the way we do now.

Its purpose wasn't to route your Netflix traffic through a server in a different country so you could watch from anywhere, or to keep your data private from a snooping ISP. It was actually more impressive: Hamachi tunneled through the maze of networks that make up the internet and navigated router firewalls to make two PCs talk to each other like they were in the same room, connected with an ethernet cable.

The connection Hamachi created was truly peer-to-peer, rather than running your data over a remote server, so it was fast. No middleman. Hamachi wasn't built exclusively for games, but it quickly became a vital tool for playing games that didn't quite have the whole internet thing figured out yet. In 2004, you could bet on a multiplayer PC game having a dead simple LAN option: if your PC was on the same local network as another one, you could join up in seconds. Online games were just starting to introduce matchmaking; port forwarding was a fresh hell or even impossible if you lived on a college campus or had a locked-down router. For years, LAN mode was a far easier and more reliable way to play a game online with just a few friends.

The first Borderlands, launched in 2009, used Gamespy for online play, which had some well-documented issues long before it shut down. So my friends and I created our own little game oasis on Hamachi to play four-player co-op, and for years after Hamachi would boot up with my PC, running in my system tray if needed.

When Risk of Rain came out in 2013, it more or less had the barebones online support of a late '90s game, demanding you type in the IP address of a host who had the right ports open on their router. Even then it was flaky and temperamental, so Hamachi was essential, quietly doing the hard work of getting our routers to play nice with each other. For months we did Risk of Rain runs on our little Hamachi LAN.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Hamachi's probably best-known as the facilitator of early Minecraft servers, and there are fresh YouTube guides to this day walking through the process. Hamachi has become less and less relevant as games have phased out LAN support or smoothed over the problems of earlier internet games. And of course it's no good for most modern multiplayer games, which use matchmaking and anti-cheat and run all traffic through their own dedicated servers.

These things all make life easier and for the most part they just work. Which is great! I don't really want to go back to a time when every online game was a potential port-forwarding minefield, and I definitely don't want to go back to playing games over dial-up. But it's easy to take "they just work" for granted. Today, one game out of a hundred not working immediately is the pea under the mattress that drives the princess (me) crazy. But back in Hamachi's era, when it was far from the norm, being able to run one little tool to bypass all those problems was a thrill.

It's up there with other annoyances of PC gaming's past that were actually fun little rituals, like defragging a hard drive or downloading a no-CD patch to play a game without the disc constantly in your drive. The more problems we streamline away, the less likely it is that a new solution will pop up and delight us. I don't miss the problems themselves, but I do miss seeing that green light and saying a silent prayer that I didn't have to spend an hour messing with my router.

I'll never be nostalgic for cleaning hair out of a ball mouse, though. Lasers forever.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).