How synthwave music inspired games to explore a past that never existed

Indie games can take us to an unreal '80s that never was.

In 2013 French electronic musician Kavinsky released a 13-track album of squelchy synths and triumphant lead lines called OutRun. It reveled in the forgotten sounds of 1980s movie scores, and the Ferrari Testarossa and palm trees on its cover referenced the 1986 arcade game the album took its title from. It’s an impeccably composed image so stylized it doesn't really resemble the game it's named after.

That’s the synthwave ethos: taking elements of a period of '80s excess millennials find irresistibly evocative, and modernizing them so they're just barely recognizable. As Robert Parker (a Swedish producer responsible for albums like Drive Sweat Play) told Time Out, "Synthwave is nostalgia with selective memory loss... [Synthwave artists] don’t really try to imitate the sounds 100 per cent, but rather take out some of the essential parts and put it in a modern context."

Kavinsky's OutRun proved so popular in the synthwave scene that it spawned its own subgenre. Quite how the music relates back to Sega’s 31-year-old racer isn’t clear, and perhaps isn’t important. What’s important is that the music inspired by a racing game went on to inspire a new wave of indie racing games.

Games like Fraoula’s Neon Drive, Denver Productions’ OutDrive, and the ill-fated Power Drive 2000 (Kickstarted in 2015 but without a developer update since February of this year) all seem to agree on the tenets of the genre: angular concept cars screeching along retrofuturist highways through a miasma of purple and pink. Tron's neon lines often appear, as do Blade Runner's cityscapes. It's an unquestionably '80s vision, but the specifics of the decade often aren't in sharp enough focus to be recognizable—least of all the games they’re homaging.

Perhaps synthwave fans couldn’t find satisfaction in revisiting the actual games of the ‘80s, so instead they created a new and imaginary vision of what games like OutRun were. Neon Drive achieves a heightened sense of 'eightiesness' by making the music an essential part of the drive. Rather than pulsing away at the periphery of the experience, the beats in Neon Drive propel the whole world forward, creating a rhythm-action racer in which you’re not so much driving the car as dancing with it—perfect synergy between sound and visuals.

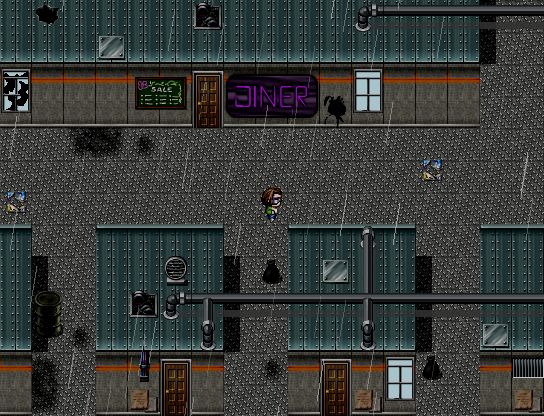

The same could be said of the game that started it all: Hotline Miami. To players of a certain age it’s the kind of gratuitous and dark entity you imagined when your parents talked about violent videogames many years ago. But even at the height of that moral panic the reality was so much tamer than Hotline Miami. Doom’s blood-specked sprites have nothing on Hotline Miami’s eye-gougings or spurting arteries, or its utterly amoral characters.

By setting itself so firmly in the 16-bit era with its visuals, Hotline Miami managed to attach itself to those original gaming boogeymen without playing anything like them. The score multipliers have at least half an eye on arcade gaming admittedly, and the top-down violence owes plenty to the original Grand Theft Auto. Yet Hotline Miami feels completely disconnected from gaming in the '80s or '90s on a mechanical level. Its quick restarts turn it into a hazy, endless dream, something that feels completely modern.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Hotline Miami's soundtrack, however, seems to gel with the pace and attitude of the game perfectly. Those 22 songs from the likes of Perturbator, Jasper Byrne, and Scattle have persistent beats matching your stubborn restarts while their glassy synth pads seem to implicitly reinforce the nihilism of the setting and dialogue. In many ways Hotline Miami is a horrible place to find yourself in, one you only stay in because you’re enjoying the violence so much. And as its creators have frequently pointed out, that was always the point.

Despite the obvious craftsmanship of both game and soundtrack, Hotline Miami was lucky to find the success that it did. Released in 2012, it found an audience who’d seen Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive in theaters just a few months prior. With a hyper-stylized period setting, violence depicted with passivity, and a soundtrack full of Kavinsky, College, and Desire, Drive put synthwave in front of a mainstream cinema audience. Its poster, with a typeface inspired by 1983's Risky Business in hot pink contrasted against its dark blues, seems to have set out an indelible vision of that aesthetic.

If Hotline Miami represents the high point for synthwave-influenced games, the following year would see its low point. Far Cry 3: Blood Dragon ticked all the boxes of the aesthetic: late '80s typography, that familiar colour palette, and an ironic repurposing of period elements (in this case the voice of Terminator and Aliens actor Michael Biehn). On paper it was primed to rewrite videogaming past like its synthwave-soundtracked brethren and offer the kind of heightened nostalgia hit you can’t get from genuinely old titles, never quite as stylish or ‘of their time’ as you remember.

The reality of Blood Dragon was a thoroughly modern open-world game with retrofuturist elements sellotaped onto it. If you were being unkind, you’d say it was Far Cry 3 with a palette swap squeezed out of Drive’s poster.

Instead of finding harmony between those elements, Blood Dragon pit them against each other. What made Far Cry 3 great was that it perfected a burgeoning frontier of open-world game design—it was an impossible task to ask a game so focused on the to new evoke something historical or nostalgic simply by changing its appearance and getting Hicks from Aliens in to record some gravelly quips.

Blood Dragon might be the first example of a game co-opting the synthwave ethos simply because it was in vogue, but it’s by no means the last. The danger with a genre of gaming and music as narrow and hard to define as this is that its output becomes reductive, simply hitting the recognizable trappings in order to give the 'come hither' finger to a hungry audience, without offering the chance to explore a remixed past that audience is really looking for.

Games under the ‘synthwave’ tag on Itch.io, for example, offer lots of stylish branding, but few seem to expand the retrofuturism concept further than that. Games about driving through the ubiquitous uncaring city, underpinned, naturally, by gated snares and John Carpenter movie synths.

Years after Hotline Miami and Drive, synthwave and indie games still enjoy a symbiotic relationship, and are still responsible for the occasional gem. Furi found a new kind of atmosphere and excitement by pairing the aesthetic with incredibly demanding boss battles in a less urban and more fantastical setting. A certain kind of listener will tell you that technically the soundtrack is 'darksynth', but the atmosphere’s very much a part of this broader movement. A steady evolution of it maybe, in which the rules are relaxed a bit.

Where that movement heads next is open to debate. It’s already had its breakthrough indie hit, and it’s already been absorbed into the mainstream. In music industry terms that means it's in trouble. To pick an example from a musical genre that's probably the antithesis of synthwave, we've had the moment where Limp Bizkit's chart success began the downfall of nu-metal. But right now at least, this little corner of gaming and music endures. As time drags us further away from the decade these games hark back to, game designers keep creating more ways to get back to it—or at least a hot pink version of it we can race through at top speed.

Phil 'the face' Iwaniuk used to work in magazines. Now he wanders the earth, stopping passers-by to tell them about PC games he remembers from 1998 until their polite smiles turn cold. He also makes ads. Veteran hardware smasher and game botherer of PC Format, Official PlayStation Magazine, PCGamesN, Guardian, Eurogamer, IGN, VG247, and What Gramophone? He won an award once, but he doesn't like to go on about it.

You can get rid of 'the face' bit if you like.

No -Ed.