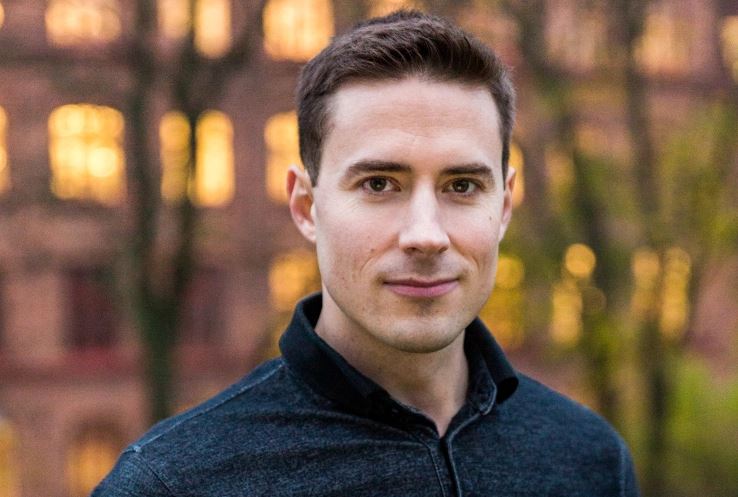

How making a new strategy game nearly destroyed Civ 5 designer Jon Shafer's life

"I had nothing left, financially, physically, or mentally," Shafer thought, halfway through the 6 years he spent on At The Gates.

At age 21, Jon Shafer was asked to be the lead designer for Sid Meier’s Civilization 5. It was a dream come true for a young designer who had been creating mods for Civ, just a few years before. Within three years of shipping Civ 5, though, he’d quit lucrative jobs at Firaxis and Stardock and suffer the crushing reality of being an isolated programming prodigy with ADHD, trying to make his dream game. It all came crashing down in 2015. "I had nothing left, financially, physically, or mentally," he wrote. "The last shreds of creativity and productivity finally slipped between my fingers."

Since 2015 Shafer has been slowly building his life back up from ruin. He spent six hard years on his passion project At the Gates, finally finishing and releasing it this January. Here's how he got there.

Strategy savant

Shafer began making his own games at a young age, programming his own Pokémon RPG and Dragon Ball Z games. At the same time he was getting into history, reading his mom’s war books and playing games like Panzer General.

"My mom was a history teacher and a fan of the old King’s Quest and Quest for Glory games, and my dad was a programmer," Shafer says. "He taught me PCD3, which was used by United for Flight Training Software back in the 80s. It was old, weird stuff but it had a graphics editor that was kind of like Paint."

His passion for strategy games and history inspired a high school teacher to introduce a teenage Shafer to Sid Meier’s Civilization 2. "My first introduction to Civilization was with a pirated copy of Civ 2!" says Shafer. "I never did buy Civ 2 but in the end I think I gave something back to the series."

Shafer poured himself into Civilization, becoming a modder and joining online communities to run civilizations as real-world democracies. After Civilization 3 released, Shafer was studying programming and history at Colorado State and began bugging Firaxis for an internship. Eventually they agreed, and Shafer began his video game career in 2005. He was 20 years old.

I never did buy Civ 2 but in the end I think I gave something back to the series.

Shafer

"My first project was Civilization 4, but honestly I wasn’t doing much," says Shafer. "I wasn’t a professional engineer and nobody knew what to do with me. I wrote a tool in Python so you could take images from a Google search, like a map of Europe, and convert them into a Civ map. I also wrote scenarios for Civilization 4, like a World War I scenario. I got involved with whatever I could get my hands on."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Firaxis had a unique company culture that allowed Shafer’s seemingly boundless energy to flourish, provided he could work on new things that piqued his interest. During the development of the Civilization 4 expansion packs, Shafer was busy prototyping new systems and total conversion mods. Shafer says he developed the entire espionage system that was introduced in Civilization 4: Beyond the Sword ("It sucked, espionage in Civ game are always terrible") as well as The Final Frontier space scenario.

Firaxis then took his work on a Colonization mod and decided to turn it into a standalone expansion, which became Civilization 4: Colonization. Shafer is credited for the original prototype. By the time work started on Colonization, though, Civ 4 lead designer Soren Johnson had left the company, and Firaxis needed someone to head Civilization 5.

Jon Shafer's Civilization

"Civ games are huge undertakings and most people only have one of those in them," says Shafer. "I felt ready. I definitely wasn’t but I felt it. I had an energy I needed to use. With Civ 5 I wanted to do new things. Civ 4 was so amazing but I didn't want to make Civ 4.5. We’re going with hexes, we’re changing combat, and the entire economy."

Firaxis handed the Civ keys to Shafer, granting him, as he puts it, "dictatorial powers" over every aspect of the game. "Firaxis has a tradition of trusting its lead designers completely, going all the way back to Microprose with Sid Meier and Brian Reynolds," says Shafer. "It’s a big job, a hard job, but so many talented people did it in the early days."

I felt ready. I definitely wasn't but I felt it.

Shafer

Shafer claims that Civilization 5 was (and still is) the biggest evolutionary leap in the franchise, and it’s hard to argue otherwise. The initial reception was divisive among hardcore fans but the game was a critical and commercial success, and would become Firaxis’ best selling Civ game to date, though Civilization 6 is on track to surpass it.

In the end, shipping Civ 5 permanently eroded his passion for the series. "I was very young and didn’t have a ton of experience. I never thought about my career path or where I was going to be in 10 years. I just always had a huge project in front my face," Shafer says. "I worked 239 days in a row to finish Civ 5. I couldn’t look at the game anymore… I was worried I’d be working on Civ forever with Firaxis. I left a few months after it shipped. I made it, I did it, but I had to go somewhere else and work on something new. I still love it but I really can’t play Civ any more; the magic’s not there."

Having Civ 5 on his resume opened up lots of opportunities. Shafer had become a name for 4X fans and studios. He landed a job at Stardock, which was coming off the disappointing release of 4X strategy game Elemental: War of Magic.

Stardock didn’t operate like Firaxis, however. "I had ideas coming off Civ and wanted to explore them in my own way. But Stardock is like me, they want to do everything." Stardock was also a much smaller company that worked on more games, leaving little room for experimentation or autonomy.

Shafer would spend only a year and a half at Stardock, though his fingerprints can be found in Galactic Civilizations 3. "Some of the features like space terrain and adjacency bonuses for buildings on planets were my ideas that I had written up and designed." At Stardock Shafer held out hope that he’d be able to design a new game, but it never happened.

Then Kickstarter exploded.

Trouble At the Gates

Shafer left Stardock and convinced his friends and roommates to help work on his dream 4X game in their spare time. After six months of work, they formed Confier Games and launched a Kickstarter campaign in early 2013, raising just over $100,000 from 3,000 backers.

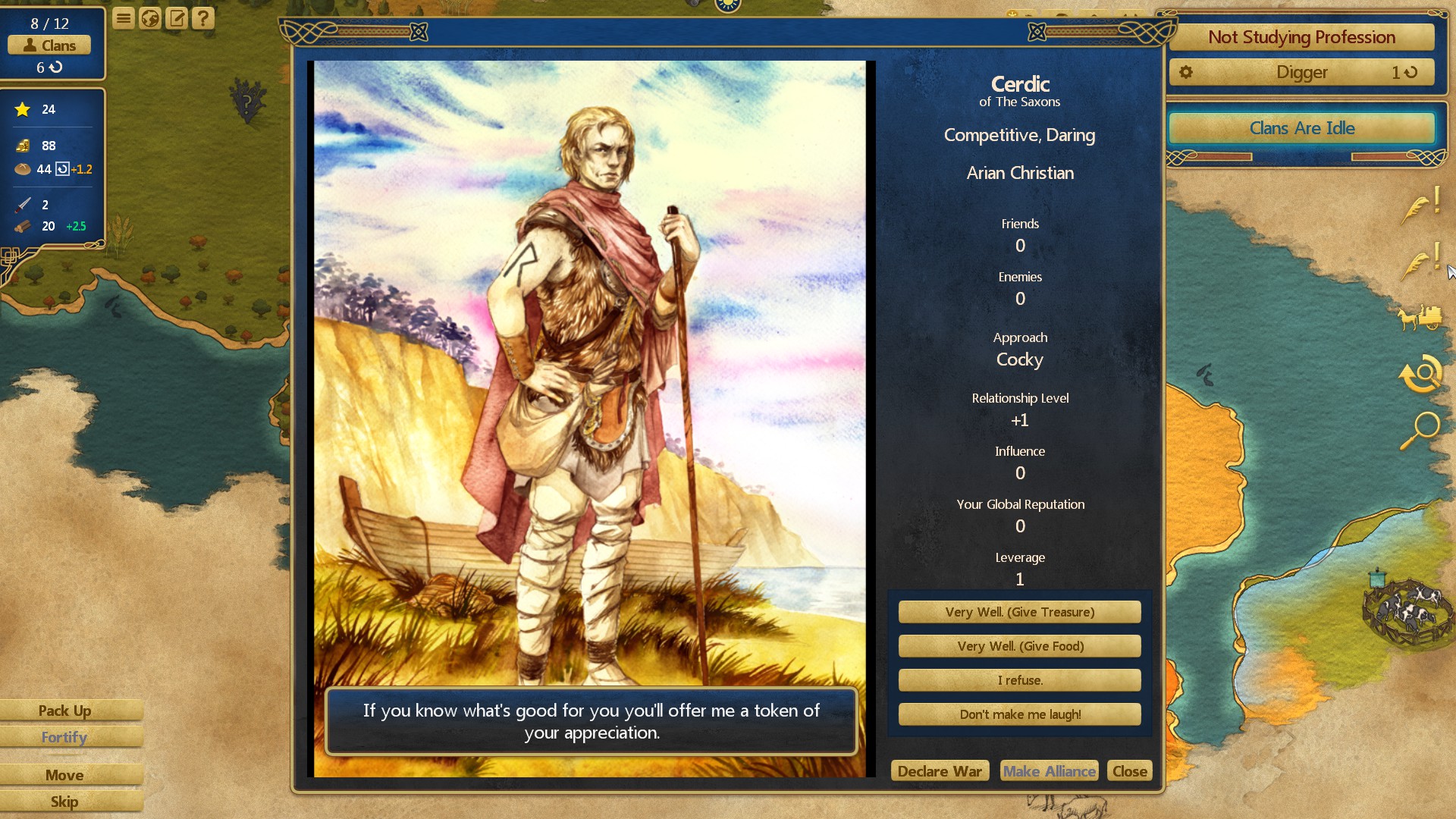

"Originally At the Gates started as a prototype of ideas," says Shafer. "A lot of 4X games have static maps, so I wanted to try cyclical map evolution, and seasons was the easiest way to do that." Shafer set the time period during the fall of the Roman Empire and founding of medieval Europe, and was inspired by Imperialism, a strategy game published by SSI in 1997.

I always kind of knew I had more trouble focusing than other people, but I was achieving a lot.

Shafer

"One of the big problems in 4X games is you quickly get bogged down when you have 20 workers and 30 cities, and you only really care about about four of them, but you keep building them up," says Shafer. "The game works against itself once you reach a certain point. Imperialism got around that problem by giving you only one city, but that capital city has a lot going on. I wanted to take that concept, along with the Roman theme and cyclical map changes, and started prototyping what would become At the Gates."

For about a year things went well. Shafer was finally free to pursue his dream 4X game. It didn't last. "In 2014 the game had several cool elements, but you weren’t building towards anything," says Shafer. "Part of the fun with Civ is seeing the visual element of your progress through roads and wonders and factories. We didn’t have that."

Inspired by Crusader Kings and King of Dragon Pass, Shafer added characters, clans, and professions to At the Gates. Professions became the entire tech tree. "It fundamentally changed the game and added a bunch of time to development. None of that was in the original game," says Shafer.

Looking back Shafer claims it was the right decision, but the extra work led him to drop life outside work, which would soon prove disastrous. "I had been diagnosed with ADHD around 2011," says Shafer. "I always kind of knew I had more trouble focusing than other people, but I was achieving a lot. I graduated high school in three years. I was the lead on Civ 5 at 21. I was never like, ‘poor me.’"

Shafer’s programming prowess and energy came at a cost; he didn’t know how to pace himself at work or how to separate work from his personal life. His social life began to crumble along with his physical and mental well-being. Around mid-2015 he stopped posting Kickstarter updates altogether.

He's uncharacteristically somber as he talks about this period of his life. "There was a couple years where I couldn’t do much of anything," says Shafer. "I stopped paying bills. It wasn’t just that this game was hard and I was feeling burned out. I was fundamentally destroyed as a person."

Breaking out of that prison and rebuilding my life has easily been the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

Shafer

Today Shafer has come through a dark period in his life. When he was working on At the Gates, he started abusing his ADHD pills, gained more than 60 pounds, and spent all of his money, which he talked about candidly in a personal blog post this January. "It finally sunk in," he wrote. "It was over. Everything was over. I had destroyed everything. There was nothing left. Of the game. Of my career. Of my life. Anything. It was all gone."

Gradually he put himself on a regimented diet and daily routine that involved eating healthily, exercising, and working regular hours, writing "breaking out of that prison and rebuilding my life has easily been the hardest thing I’ve ever done." Ultimately one of the best decisions he made for his road to recovery was moving to Stockholm, Sweden to pursue yet another big name 4X video game developer, Paradox Interactive.

"With Paradox I wanted to be in a more structured environment, and not just sitting at a desk by myself. Plus, I had no money left."

While at Paradox, Shafer’s contract allowed him to continue working on At the Gates, and he soon felt like he was working two jobs at once. Six months later, Shafer would quit Paradox, largely for the same reason as Stardock. "I had my own games I wanted to make," says Shafer. "The expectations were completely different to how I was used to making games. The Firaxis and Paradox models are very different from each other. I know how to make good games, but I need an environment that gives me creative freedom. That’s what I was used to at Firaxis."

Paradox didn’t work out, but Sweden provided a new life for Shafer. "I made a lot of friends there—I have a Swedish girlfriend!" says Shafer. "I love it there. Living in a city is awesome. I grew up in the suburbs of Denver, Baltimore, and Detroit. Now I’m in downtown Stockholm and there’s so much to do and see."

Shafer is well aware that the tumultuous six years he spent on At the Gates wasn't sustainable or healthy. "With At the Gates I didn’t really have milestones and wasn’t very disciplined with scope," says Shafer. "I’m going to change how I do things from now on. The one guy in a room by himself, I did that to finish At the Gates."

Shafer plans on taking some time off after At the Gates' launch, with Dead Cells as the game he’s most excited to play. Afterwards he already has plans for his next game, ones he’s had for a long time, but he’s not ready to announce it yet.

When asked if he has any advice for young developers, he stresses the work-life balance and the importance of taking care of yourself. "This is the kind of business where folks, especially younger developers, really give it their all," says Shafer. "But it’s incredibly easy to burn out this way, and once you do that passion that drives you will go away. I’m not going to tell people how to live their lives, but look after yourself and establish healthy work and life habits."