How a remake of an obscure 1995 FPS led to a retro shooter revival

'90s shooters escaped their certain Doom with an indie retro revival.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

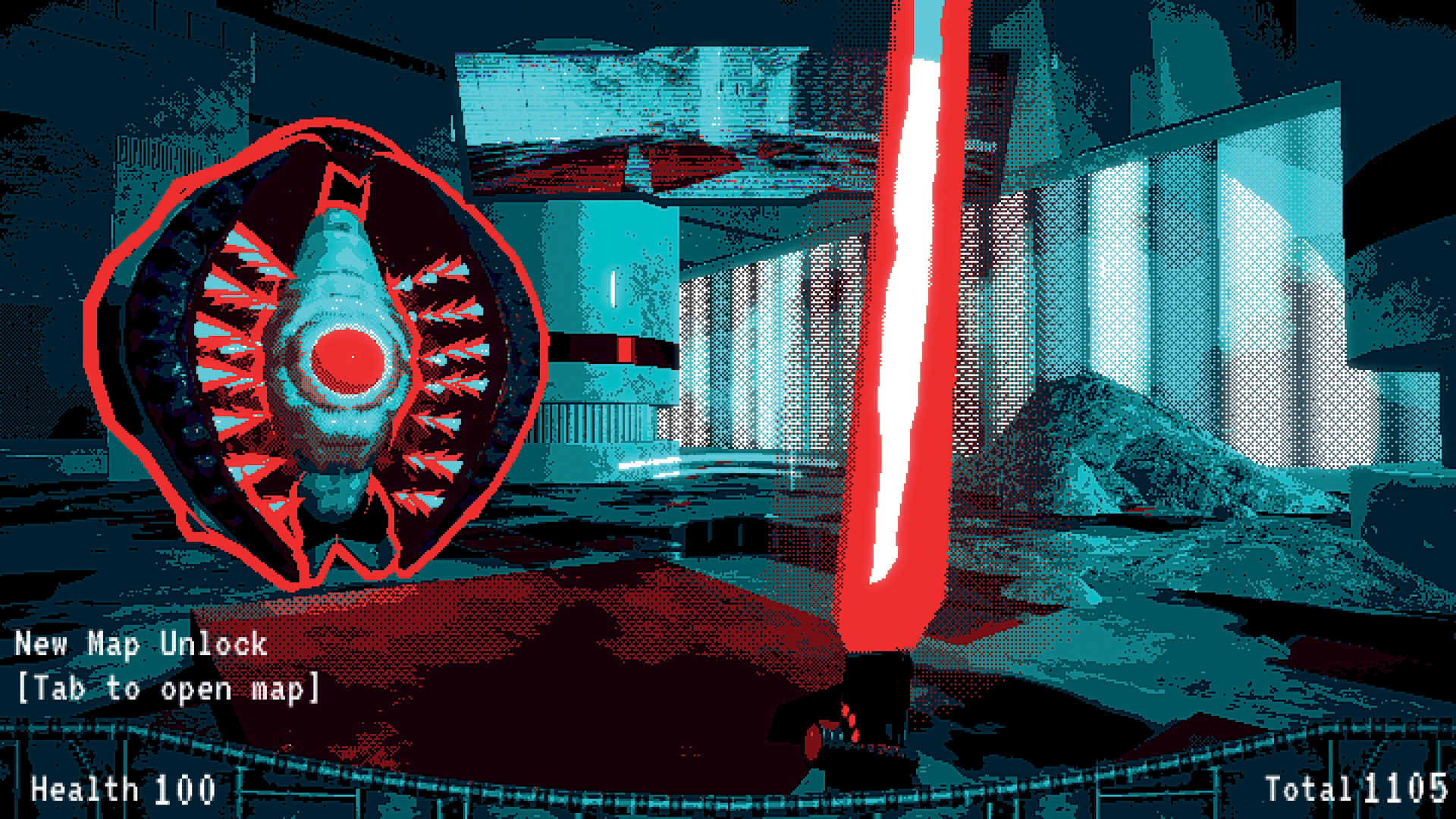

If you tuned into 3D Realms’ Twitch channel last September, you could be forgiven for thinking you were peering through a portal into 1997. The publisher held the inaugural Realms Deep event, two days of lightning-fast frags and chunky gibs, weapon sprites and the kind of character models where you could count the polygons by eye, all with a soundtrack that can only be described as ‘pumping’.

Dave Oshry, CEO of New Blood Interactive, describes it as "our own E3 for retro shooters". It’s a party for developers who believe the first-person shooter was perfected by the turn of the millennium and, rejecting all those heretical texts which followed, have spent the past half-decade striving to resurrect the look and feel of the ’90s golden age. This might sound like a regressive way of making games—and it certainly can be—but this movement has produced some of the highest-rated games on Steam. And you can trace almost its entire history back to one unlikely game: Rise of the Triad.

It was the remake of a 1995 shooter that Frederik Schreiber, now VP of 3D Realms, admits was "an obscure, kind of unknown game to the masses". And he should know—in 2013, along with Oshry, Schreiber was one of the game’s directors. The remake isn’t much better remembered, but it happened to mark the beginning of a broader revival, the names getting bigger with each release: Shadow Warrior, Wolfenstein: The New Order, Doom.

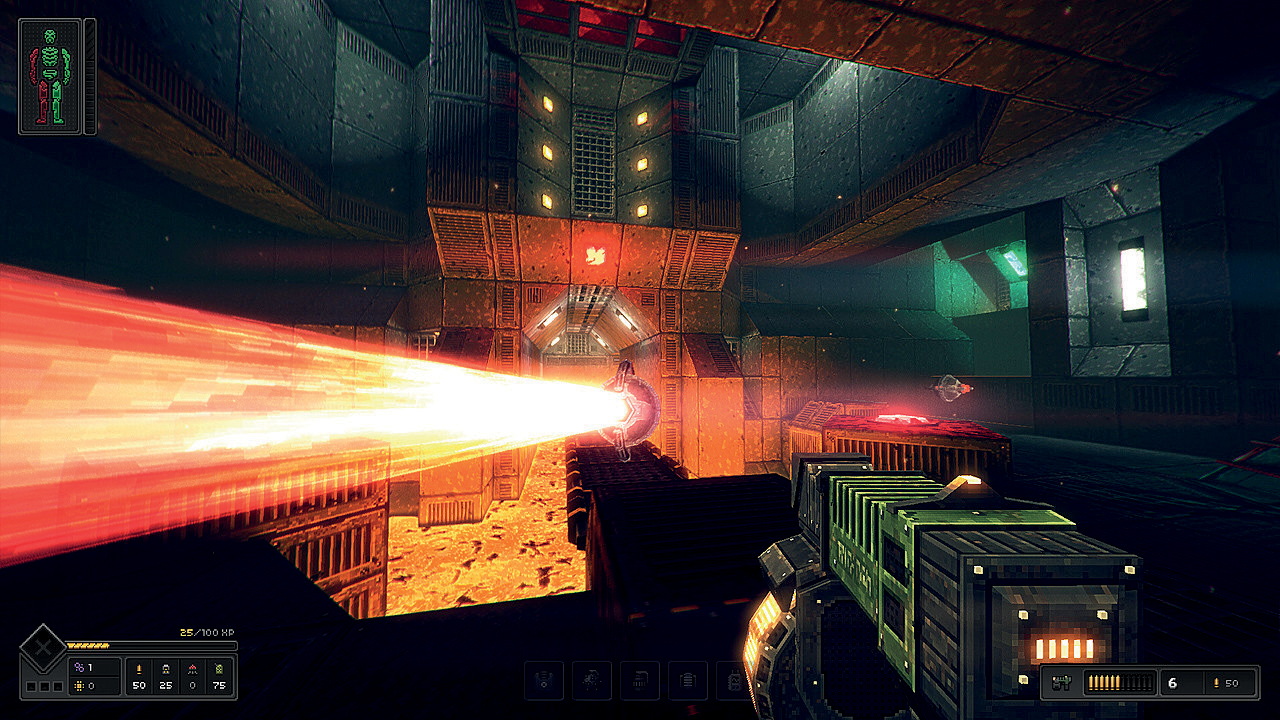

The release led—via a few cancelled projects and a lot of Duke Nukem-related lawsuits—to acquiring 3D Realms, the publisher behind so many of the shooters that defined Schreiber's childhood, and reviving its reputation with games like Wrath: Aeon of Ruin and Ion Maiden, the first game in two decades to be made using the Build engine.

For Oshry, it was the reason David Szymanski, a fan of the remake, got in touch to share a prototype he’d been working on. Oshry fired up the one-room demo to check it out. "It was all there: the movement, the shooting, the interactivity," he remembers. "You could flush the toilet!" This was Dusk, a Quake- meets-Doom horror shooter that’s generally considered a high watermark of this revival—and it transformed Oshry’s company, New Blood, into a purveyor of retro-flavoured delights.

Respawn

These two companies are the cornerstones of the indie retro shooter revival, but they’re far from the total of it. I could rattle off names (Prodeus, Hrot, Hellbound) like rounds from a chaingun, but the more important point here is: why, 20 years after its heyday, has this style of games returned?

"For years before I’d been frustrated no one was making games like this," says Szymanski. He’d grown up with Doom and Quake, and modern shooters simply weren’t scratching the same itch. I hear a similar story from Thom Glunt, designer of another early outrunner, Strafe. "There were only a few throwback FPS games at that time," Glunt says—and, while they borrowed the fast gunplay of the classics, all these shooters stuck to a modern graphical style. "I personally hated that. I wanted those beautiful, crunchy, low-poly vibes, and it felt like many devs were scared of it or didn’t see the beauty."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

That’s not the case today. If you’ve got a hankering for the early 3D of Quake or the spritely majesty of Build engine games like Blood, you’ll find multiple titles catering to your needs. Think of it as the successor to the 8-bit aesthetic that’s ruled over indie games for the past decade, with similar benefits for a smaller development team. But that’s not the whole story. "We don’t see rendering techniques as mere steps in an inevitable linear progression," says Jon Marshall, one third of Devil Daggers creator Sorath. "They can be valid tools in their own right, just as black-and-white film photography or hand-drawn animation retain their own quality distinct from later digital colour photography or CGI."

Secret agency

Devil Daggers strips the retro shooter back to its barest essentials. The world recedes into darkness a few feet from your face, the shadows spewing floods of enemies. You have a single weapon to repel them: your hand, which for some unexplained reason can shoot energy. You hold on for as long as you can—each decimal point of a second hard-fought—and then try to beat that score. This throws a stark spotlight on the simple feel of moving and shooting, something all the developers I speak to are trying to recapture. "I spent a lot of time studying what makes Doom’s combat so much fun," Szymanski says of Dusk.

But Devil Daggers also cuts away another treasured aspects of these games: the level design. The classic ’90s approach, Szymanski says, was using "shortcuts and backtracking to make the level itself an experience, and not just a series of environmental setpieces in what effectively amounts to a hallway". Dusk’s levels are a great example of the form, looping around and inside of themselves, as if artist M. C. Escher was set loose with Doom’s modding tools.

And that’s without mentioning the secrets. In Dusk or Ion Fury, it’s not just about skidding around like you’ve got an Acme-equipped coyote on your tail. To get the best stuff, you’ll need to slow down, study the wall textures for a telltale crack or discolouration. Tap the use button, and a panel might slide away, putting a new weapon in your hands, or even leading to an entire secret level.

Knee deep

Coming from modern shooters, the thing that stands out most is the refreshing lack of interest in imitating reality. Maps are explicitly death traps, the level designer as cackling Bond villain, with a conveyor belt of enemies to headshot. They don’t all take it quite as far as Devil Daggers, but these games are essentially the first-person shooter with everything removed but the engine.

The rest "no cutscenes, carry all the weapons you want, ludicrous gibs, run really fast, no tutorials" as Oshry effortlessly rattles off for me, before adding "monster closets and coloured keys and doors everywhere" too—that’s all just optional set dressing, really. Oshry understands the value of these nostalgic signifiers, and New Blood’s marketing leans heavily on it.

But nostalgia really is a funny thing. Here in 2021 especially, it’s difficult not to indulge in the idea that the past is a warm and safe place for everybody. Which, obviously, is some way from the truth. By shutting out more recent work, you’re likely to narrow the range of voices you hear—something that has certainly plagued Ion Fury, with its post-launch dithering over whether to remove two homophobic jokes of the playground variety, the sort of jokes that you’d expect from the original Duke Nukem games. But even putting that aside, if nostalgia becomes your only guiding principle, it’s unlikely to aid creativity very much. After all, why shoot for the future when the past is already there waiting?

Thankfully, everyone I speak to agrees. "I felt that if we’d have made a Quake clone, then why would we ask for money for it? It should have just been a Quake mod," Glunt says of Strafe. Even Schreiber, who approaches these old games like a watchmaker, a loupe held up to their inner workings, replicating every technical limitations perfectly, is firm that "all the things that didn’t age well, we’re cutting out".

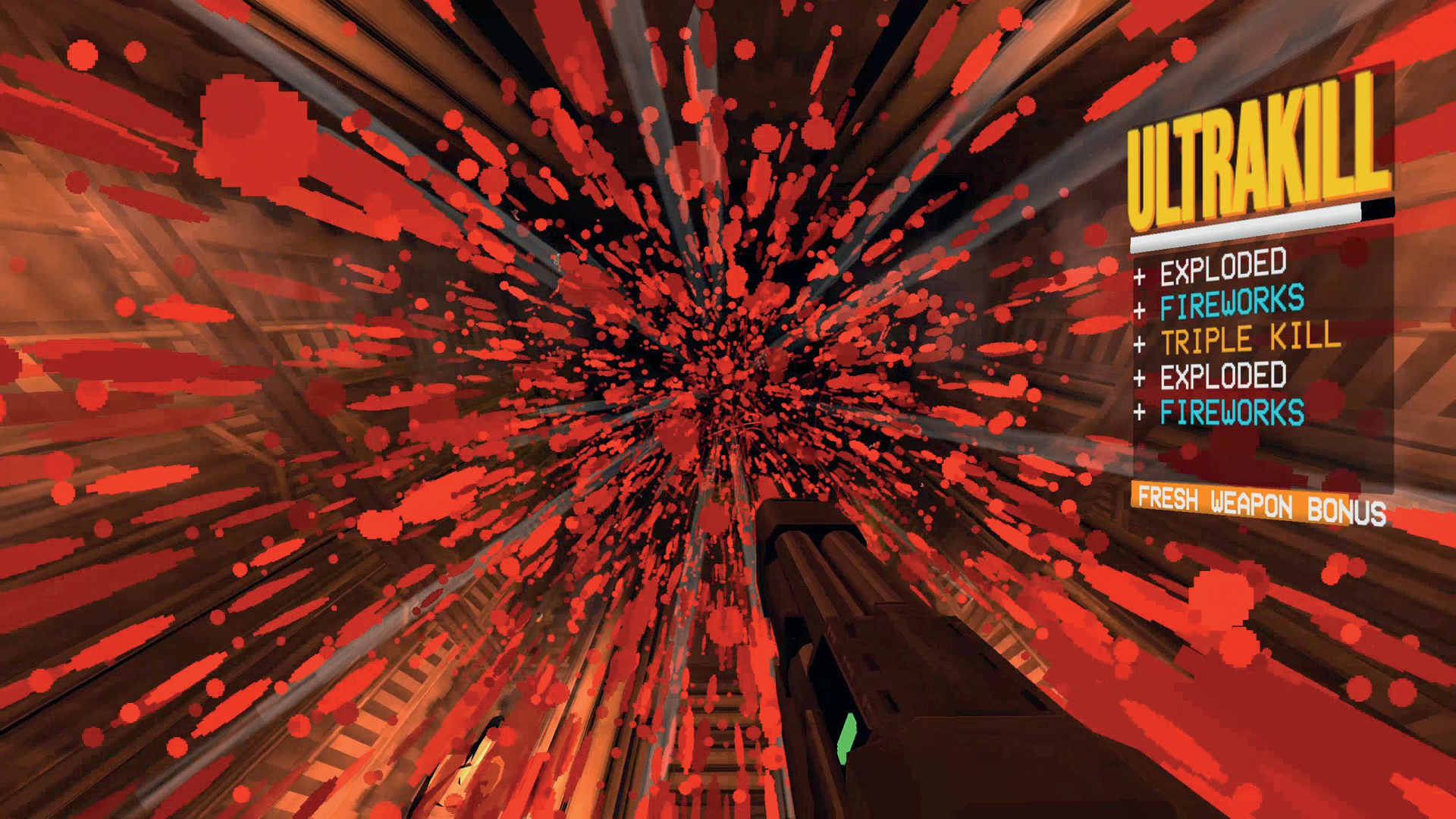

Oshry—who insists he’s trying to stop putting out retro shooters, only to have something new and shiny catch his eye—says you can’t just copy what came before, whether that was in 1993 or 2017. "It has to be something different." Take Ultrakill, the studio’s latest. There’s a dash of Devil May Cry in its wall jumps and style meter, but more important is the idea of taking all that blood and mechanising it, so that the only way to heal is to bathe in the showering arteries of a dispatched foe.

Every game in this revival—at least, all the ones worth playing—conceals an idea like this, its own little twist on the formula. "I think that that’s the beauty of this retro shooter wave," Schreiber says. "All of the games that come out, they have different aesthetics, they have different goals, they all have different ways of making their games."

Game over?

It’s pretty undeniable that Oshry, Schreiber, and comrades have won—we’re no longer short on the old-school thrills they felt deprived of back in the early 2010s. Does that mean their audience has been sated? "All trends move on," Oshry shrugs. "I’ve ruffled some feathers by saying, if you’re starting work on a retro shooter now, you’re probably two years too late."

Schreiber describes 3D Realms’ recent output as an alternate timeline, moving through the ’90s on fast forward—and it’s rapidly closing in that millennial boundary. "Where we are now with Graven is kind of the limit," he says. "In terms of visual fidelity, the problem with making an early 2000s game is that, for the majority of people, it will look like a very ugly modern game, rather than a really pretty old game. We can always go back in time, but that’s the limit."

The answer, it seems, is diversification. 3D Realms is also publishing Ghostrunner, which applies the speed of a retro shooter to create something entirely its own. "We’re going to do more AAA indie stuff like that," Schreiber says, although he acknowledges they’re much more expensive to make. For New Blood, meanwhile, retro definitely remains its niche, but that reaches well beyond shooters. "All the cool kids are making retro immersive sims these days," Oshry says, a nod to the studio’s upcoming Thief-a-like Gloomwood.

But the retro shooter party’s not over just yet. Many of the games mentioned here aren’t even out yet, Schreiber intends to bring Realms Deep back for another year, and you get the impression that Oshry’s efforts to stop making these games will fail. And if it does all end, well, we’ll see you back here in another 20 years for the next revival.